AliasCheck and Num2Bits_strict in Circomlib

An alias bug in Circom (or any ZK circuit language) occurs when a binary array of signals encodes a number larger than the field element can hold. We will refer to signals and field elements interchangeably in this article. We refer to the characteristic of the field as p. Loosely speaking, p is the value the signal "overflows" at. It is the value of the implicit modulo in all of the arithmetic operations.

By default, Circom sets p to be 21888242871839275222246405745257275088548364400416034343698204186575808495617, which takes 254 bits to store. However, $2^{254} – 1 (\sim2.89\times10^{76})$ is larger than the default p ($\sim2.18\times10^{76}$). That is, 254 bits can encode numbers larger than Circom signals can store.

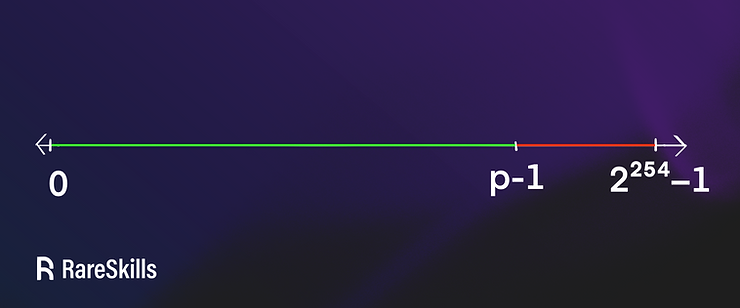

Below we plot the number line showing these values on a number line, approximately to scale:

0 to $p – 1$ (the green line segment) is the interval a Circom field element can hold, and p to $2^{254} – 1$ (the red segment) is the values a 254 bit binary value can hold, but a field element cannot.

The "danger zone" is 254 bit binary values larger than p - 1. These are the numbers in the interval $[p, 2^{254} − 1]$. In Circom’s (default) case, the range $[p, 2^{254} − 1]$ is

[21888242871839275222246405745257275088548364400416034343698204186575808495617, 28948022309329048855892746252171976963317496166410141009864396001978282409983]

To get a sense of scale, if we divide $p / 2^{254}$ we get 0.7561, which means a p can hold approximately 3/4ths of the numbers representable by a 254 bit number.

Binary representation constraints silently fail when they overflow

To constrain a binary number $b₀, b₁, …, bₙ$ to equal a field element v, we write the following arithmetic circuit:

and also constrain each $bᵢ$ to be $0$ or $1$.

However, the computation $v = b_0 + 2 * b_1 + … + n * b_n$ is done modulo p. Therefore, if the computation $b_0 + 2b_1 + … + nb_n$ overflows p, then we could present a binary number $b_0, b_1, …, b_n$ whose value is not v and create a false proof. For example, if our modulo is 11, then 2 and 13 are "equal" to each other because 13 mod 11 is 2.

Small example

Suppose $p = 11$ and we are using four bits to represent a field element. The bits can encode numbers as large as 15. If we encode 12 in binary as (1100) this will evaluate to 12 modulo 11 = 1. So we can claim that 1100 is the binary representation of 1.

Specifically:

$8(1) + 4(1) + 2(0) + (0) == 1 (\mod 11 )$

Demonstration in Python

To see the values being used by the attacker, below we recreate the constraint used by Circomlib’s Bits2Num and Num2Bits in Python so that the values can be easily printed out:

p = 21888242871839275222246405745257275088548364400416034343698204186575808495617

# replicates the constraints Num2Bits and Bits2Num use

def constrain_modulo_p(bits, num, p):

multiplier = 1

acc = 0

for i in range(len(bits)):

assert bits[i] == 0 or bits[i] == 1

acc = (acc + multiplier * bits[i]) % p

multiplier = (multiplier * 2) % p

# binary conversion must be correct

assert num == acc

# this cannot be done in Circom because `value` needs to be higher than p

# but less than 2^254 - 1

def malicious_witness_generator(nbits, value):

bits = []

for i in range(nbits):

bit = value >> i & 1

bits.append(bit)

return bits

# "normal" case -- constraints pass

constrain_modulo_p([1,1], 3, p)

# adversary case -- constraints pass, but the binary number is not 3

adversary_bits = malicious_witness_generator(254, 3 + p)

print(adversary_bits)

# no asserts are triggered although adversary_bits ≠ 3

constrain_modulo_p(adversary_bits, 3, p)The important thing here is that constrain_modulo_p accepts two binary representations for 3: the "correct" binary representation for 3 (11), and it’s alias $3 + p$ — which is encodable with as a 254 bit number.

Bug prevention with AliasCheck and Num2Bits_strict and Bits2Num_strict

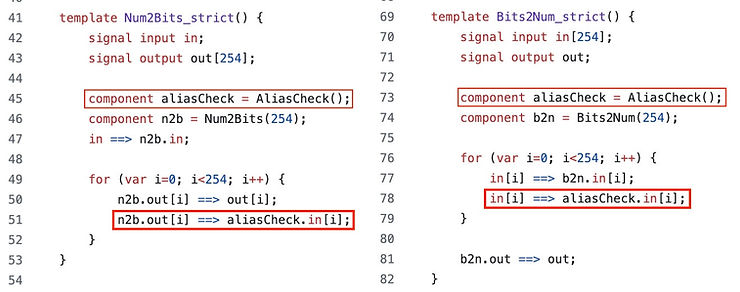

The "strict" versions of the bit conversion templates in Circomlib’s bitify library prevent the alias bug by passing the binary array to the AliasCheck template.

The AliasCheck template takes a binary array and asserts that the value encoded is less than the maximum value the field element can hold

pragma circom 2.0.0;

include "compconstant.circom";

template AliasCheck() {

signal input in[254];

component compConstant = CompConstant(-1);

for (var i=0; i<254; i++) in[i] ==> compConstant.in[i];

// compConstant returns 1 if the binary

// input is greater than the supplied constant

compConstant.out === 0;

}

AliasCheck uses -1 to refer to p - 1. compConstant takes a binary input (which could encode a value larger than the field element can hold) and returns 0 if it is less than or equal to a certain threshold and 1 if the binary value is greater than the threshold.

By constraining the output of compConstant to be 0, and setting the constant for comparison to be -1, AliasCheck disallows binary numbers that are larger than p.

If the binary array holds fewer bits than the field can encode, there is no danger of alias bugs

Applying Num2Bits to a field element also enforces a range check on that number to be less than $2^n$ where n is the number of bits. For example, if n = 4 and p is the default value, and we set the input signal to be 17, the result will not silently overflow to binary 1 (0001) — the circuit will not be satisfied.

This is why Num2Bits_strict and Bits2Num_strict in Circomlib have the number of bits hardcoded to 254 — this is the value at which aliases can appear.

This is also why the LessThan template doesn’t allow the dev to build a comparator with more than 252 bits. This avoids a footgun with the alias bug.

template LessThan(n) {

assert(n <= 252);

signal input in[2];

signal output out;

component n2b = Num2Bits(n+1);

n2b.in <== in[0] + (1<<n) - in[1];

out <== 1-n2b.out[n];

}If you change the default p in the Circom compiler (the -p option), be sure to check that Num2Bits_strict, Bits2Num_strict, AliasCheck, and CompConstant still protect you from alias bugs because they are hardcoded to use 254 bits.

Spot the bug challenge

Here is a CTF we posted on X (formerly Twitter) that has the bug described in this article:

pragma circom 2.1.8;

include ".node_modules/circomlib/circuits/comparators.circom";

include ".node_modules/circomlib/circuits/poseidon.circom";

template UnsafePoseidon(n) {

signal input in;

signal output out;

component n2b = Num2Bits(n);

component b2n = Bits2Num(n);

component phash = Poseidon(1);

n2b.in <== in;

for (var i = 0; i < n; i++) {

b2n.in[i] <== n2b.out[i];

}

phash.inputs[0] <== b2n.out;

phash.out ==> out;

}

component main = UnsafePoseidon(254);The problem with the code above is that there are multiple witnesses that lead to the same hash, due to allowing 254 bits which leads to overflow.

Remember, the input to an arithmetic circuit is not only the signals labelled input its every signal in the circuit. Circom provides us a nice C-like programming language to "fill in" some of the signals based on the values provided in the input signals, but the code is not part of the final constraint system.

In the code above, the 254 bit binary array is held in the output signals of Num2Bits and the input signals of Bits2Num.

To inject the wrong values into the signals used to encode the binary array, we need to use the technique describe in our tutorial on hacking underconstrained Circom circuits. To generate a proof of concept for the code above, we take the following steps.

- Generate a hash using a number

uwhich is small enough to have an alias in the range, i.e. $[p, 2^{254} − 1]$. - Generate malicious witness using the same number applied to

input inbut reassign the binary array to hold the valueu + p. - The hash generated by both of these signal assignments will be the same, but the witness is different.

In summary, the code in the challenge is vulnerable to a second preimage attack via an alias bug.

Originally Published Jul 13