Introduction

The biconditional operator enables us to assert if-and-only-if relationships between boolean values. Implication (P => Q) states that if condition P is satisfied, then Q is observed. The biconditional adds the reverse requirement: if Q is observed, then condition P must also be satisfied. In other words, P <=> Q is equivalent to asserting both P => Q and Q => P.

NOTE: The reader is assumed to have already read the chapter “Implication Operator”, as it lays the foundation for this chapter.

setX() Function

Let’s start with a basic setter function. It takes a uint256 input and updates the storage variable x, but only if the new value is strictly greater than the current one. This restriction is enforced using a require statement, which reverts the transaction if the condition is not met:

/// Solidity

uint256 public x;

function setX(uint256 _x) external {

require(_x > x, "x must be greater than the previous value");

x = _x;

}

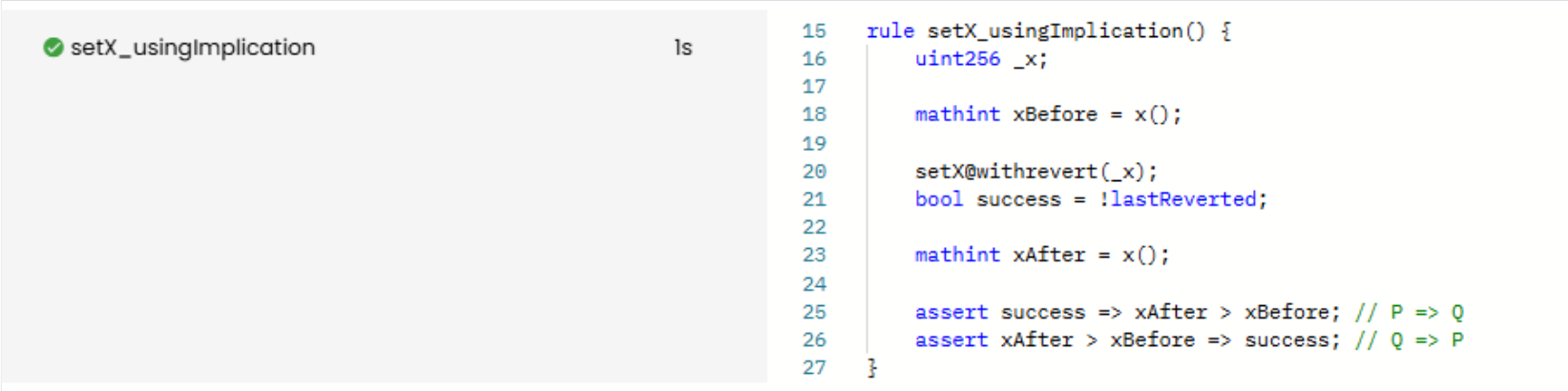

To formally verify this function using the implication operator, we can express the relationship between the transaction’s success and the resulting state change as two assert implication statements:

rule setX_usingImplication() {

uint256 _x;

mathint xBefore = x();

setX@withrevert(_x);

bool success = !lastReverted;

mathint xAfter = x();

assert success => xAfter > xBefore; // If the call succeeds, then x increased (P => Q)

assert xAfter > xBefore => success; // If x increased, then the call must have succeeded (Q => P)

}

Prover run: link

While logically correct, writing two one-way implications (P => Q and Q => P) is unnecessarily verbose.

Biconditional (<=>) in CVL

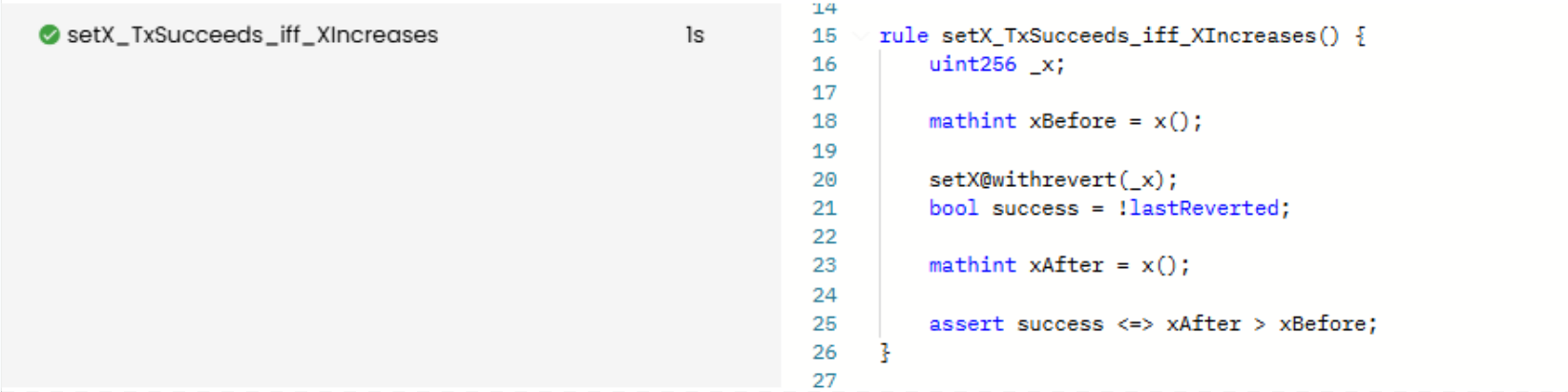

The intent here is to express a precise rule: “the transaction succeeds if and only if the input value is greater than the current value of x.”

This can be written more cleanly as:

rule setX_TxSucceeds_iff_XIncreases() {

uint256 _x;

mathint xBefore = x();

setX@withrevert(_x);

bool success = !lastReverted;

mathint xAfter = x();

assert success <=> xAfter > xBefore;

}

This single assert biconditional statement is more concise and directly expresses the two-way relationship between the call’s success and the change in state x (increase). In other words, the function only succeeds if x increases, and x only increases if the call succeeds.

As expected, this rule verifies:

Prover run: link

Implicitly, we can also reason that: if the call failed, then x did not increase:

assert !success <=> !(xAfter > xBefore);

or

assert !success <=> xAfter <= xBefore;

This is already implied by the biconditional and does not need to be written separately.

Formally Verifying Solmate’s mulDivUp()

In the previous chapter (Implication Operator), we discussed the behavior of Solmate’s mulDivUp() function, its overflow checks, and rounding logic. Here’s a quick recap:

- It reverts if

denominator == 0(division by zero) or ifx * y > MAX_UINT256(overflow). mulDivUp(x, y, denominator)multipliesxandy, divides the result bydenominator, and rounds up if there’s a remainder; otherwise, it returns the exact quotient.

Now let’s formally verify these behaviors using the biconditional operator.

Revert Behavior

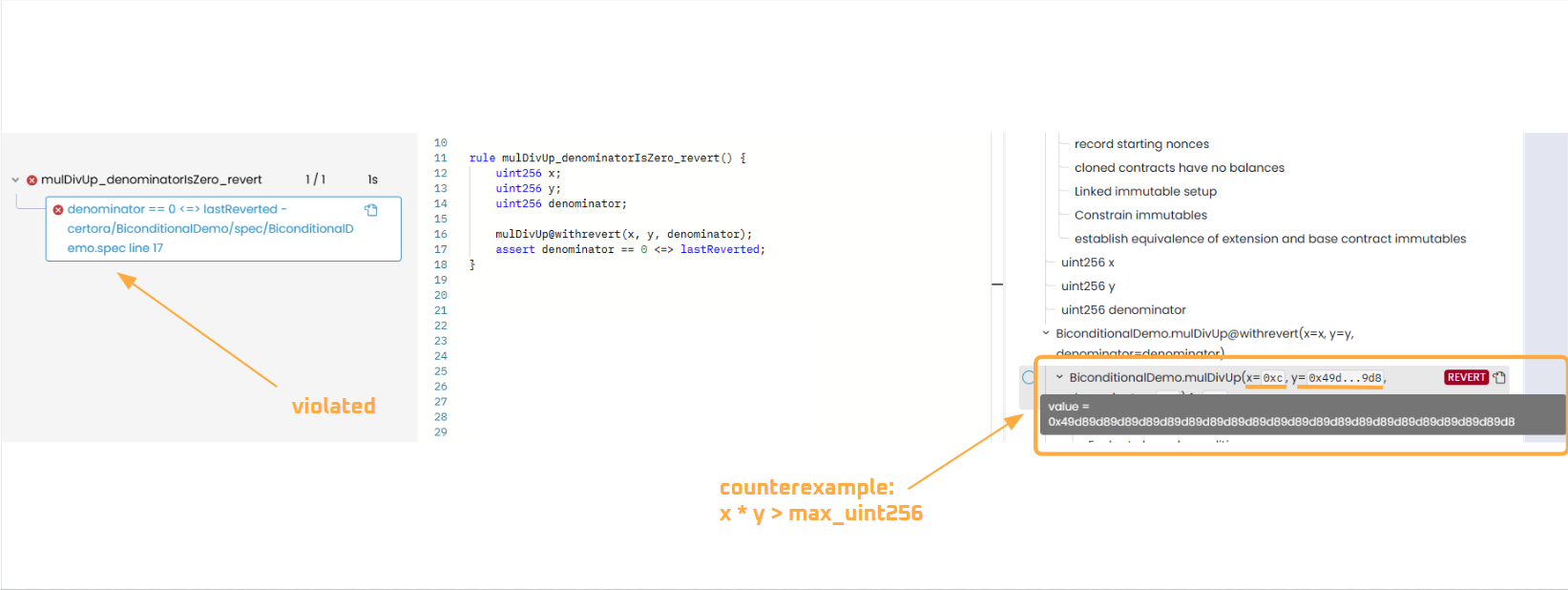

Let’s start with the revert behavior. We begin by writing the simplest revert condition, denominator == 0, then work our way up to a complete rule.

This will fail, as we know, because it doesn’t capture all revert scenarios, but it serves as a good starting point:

rule mulDivUp_denominatorIsZero_revert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert denominator == 0 <=> lastReverted;

}

The rule fails due to a counterexample where the product of x and y exceeds max_uint256. We need to include that as an additional revert condition:

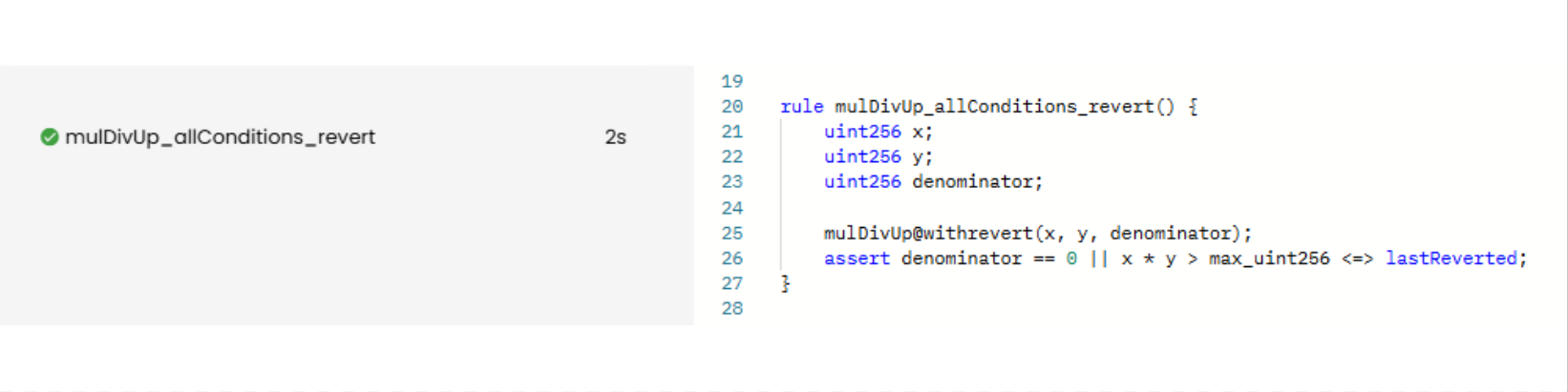

Here’s the corrected CVL rule:

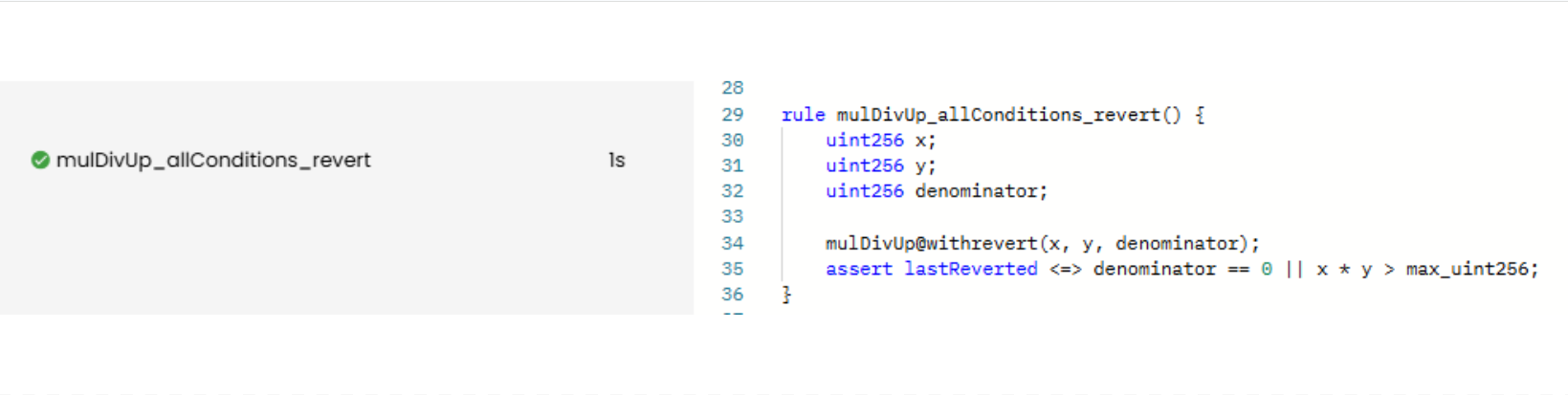

rule mulDivUp_allConditions_revert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert denominator == 0 || x * y > max_uint256 <=> lastReverted;

}

Prover run: link

Note that the biconditional is reversible (unlike implication), so we can rewrite the assertion like this:

rule mulDivUp_allConditions_revert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert lastReverted <=> denominator == 0 || x * y > max_uint256;

}

Prover run: link

Also, since a biconditional is a combined two-way implication (P => Q and Q => P), the two are logically bound together; therefore, expressions reasoned through <=> are inseparable.

Rounding Behavior

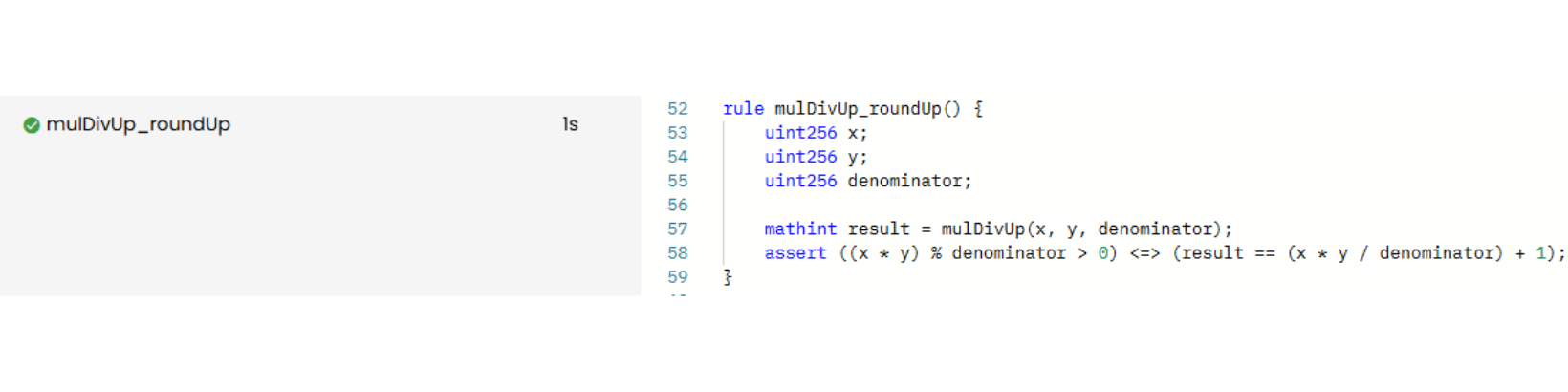

The rule below specifies the rounding behavior of the mulDivUp() function. It asserts that the function returns a rounded-up value if and only if a remainder is present. The biconditional operator guarantees that a remainder is the sole condition that triggers rounding up and that no other condition can affect the return value:

rule mulDivUp_roundUp() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mathint result = mulDivUp(x, y, denominator);

assert ((x * y) % denominator > 0) <=> (result == (x * y / denominator) + 1);

}

Prover run: link

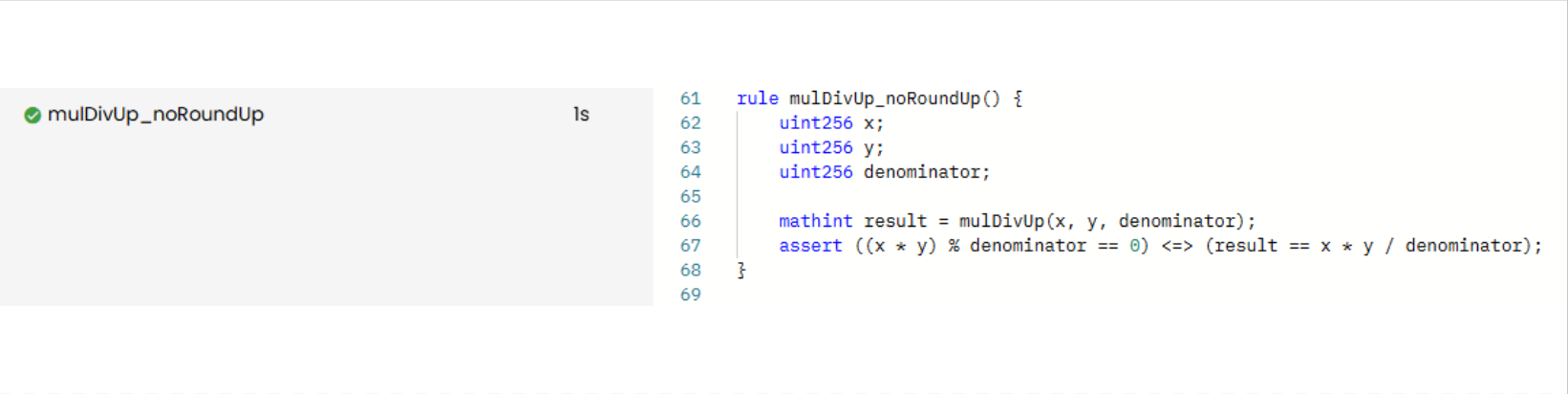

The rule below covers the “other” case. It asserts that the function returns the exact quotient if and only if there is no remainder. The biconditional operator guarantees that the only reason for returning an unrounded result is the absence of a remainder:

rule mulDivUp_noRoundUp() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mathint result = mulDivUp(x, y, denominator);

assert ((x * y) % denominator == 0) <=> (result == x * y / denominator);

}

Prover run: link

When To Use Biconditional Over Implication

Exclude Uncertainty

The rule above, as we saw in the previous chapter, can be written using => because the property being verified happens to have only one condition that leads to the outcome. In such cases, => can be replaced with <=>. This replacement is preferable because <=> states that nothing other than the specified condition can cause the outcome. The implication operator does not provide this guarantee, so in cases like these, it is better to use the biconditional to make that guarantee explicit.

In the previous example (max function), we accounted for all the revert conditions because we were verifying the function’s correctness as a whole. However, when dealing with a function that calls several internal functions, each potentially causing different revert conditions, using an implication can be more practical. This approach focuses only on the necessary condition(s) for reverting, without exhaustively dealing with every possible failure scenario.

Verify Mutual Dependency

Mutual dependency occurs when two variables are interdependent, meaning a change in one triggers a corresponding change in the other, and vice versa.

Take an AMM WETH/USDC pool as an example: During swaps, the WETH balance increases if and only if the USDC balance decreases, and vice versa. This creates a two-way dependency where the balance of one token must adjust in response to changes in the other, indicating that neither balance can change independently.

Summary

- The biconditional (

<=>) explicitly guarantees the implication in both directions. If condition P is satisfied, Q holds, and if Q holds, condition P must also be satisfied. - The implication operator (

=>) works when condition(s) lead to an outcome, but it doesn’t guarantee that the outcome can only be caused by that condition. - Using biconditional can be impractical when there are a lot of potential conditions that result in the outcome.

Exercises for the reader

- Formally verify Solady min always returns the min.

- Formally verify Solady zeroFloorSub returns

max(0, x - y). In other words, ifxis less thany, it returns0. Otherwise, it returnsx - y.