In the previous chapter, we learned how ghost variables allow information to flow from hooks into rules. We also learned that:

- At the start of the verification run, the Prover chooses arbitrary (havoced) values for a ghost variables.

- Ghost variables are treated as an extension of the contract’s storage. If a transaction reverts during symbolic execution, the Prover also reverts any ghost updates from that path, keeping them consistent with the contract’s storage state.

The second case isn’t usually a concern, as reverting ghost values during transactions mirrors normal storage behavior. However, the first case can lead to incorrect or misleading verification results.

In this chapter, we will demonstrate how this issue can affect verification and explain how to fix it by establishing consistency between ghost variables and the contract state using the require statement.

Understanding the Danger of Unconstrained Ghosts

To see how an unconstrained ghost variable can affect verification, let’s revisit the Counter contract used in earlier chapters.

//SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.24;

contract Counter {

uint256 public count;

function increment() external {

count++;

}

}

Consider the specification below, which is intended to verify that every call to the increment() function properly increases the count variable. It ensures that the total change in count matches the number of times the function was invoked, as tracked by the ghost variable countIncrementCall.

methods {

function increment() external envfree;

function count() external returns (uint) envfree;

}

// Ghost variable to track how many times the `count` variable is updated

ghost mathint countIncrementCall;

// Hook triggered before `count` is updated via SSTORE

hook Sstore count uint256 updatedValue (uint256 prevValue) {

// Increment the ghost each time `count` is about to be modified

countIncrementCall = countIncrementCall + 1;

}

/*

*Rule to verify that count increases by exactly the number of times increment()

is called

*/

rule checkCounterIncrements() {

// Capture the value of `count` before any updates

mathint precallCountValue = count();

// Perform three increment operations

increment();

increment();

increment();

// Capture the value of `count` after updates

mathint postCallCountValue = count();

// Assert that `count` increased by the same amount as tracked by the ghost

assert postCallCountValue == precallCountValue + countIncrementCall;

}

The above spec does the following:

- We declare a ghost variable,

countIncrementCall, of typemathintto act as our independent counter. - We use an

Sstorehook that watches thecountvariable. Every time the contract writes a new value tocount, this hook is triggered and it increments thecountIncrementCallghost. - The rule

checkCounterIncrementsestablishes a test scenario. It reads the initial value ofcount, callsincrement()three times, and then reads the final value. - Finally, it asserts that the final count must equal the initial count plus the number of increments tracked by our ghost. Since we called

increment()three times,countIncrementCallshould be 3, so the assertion is expected to hold.

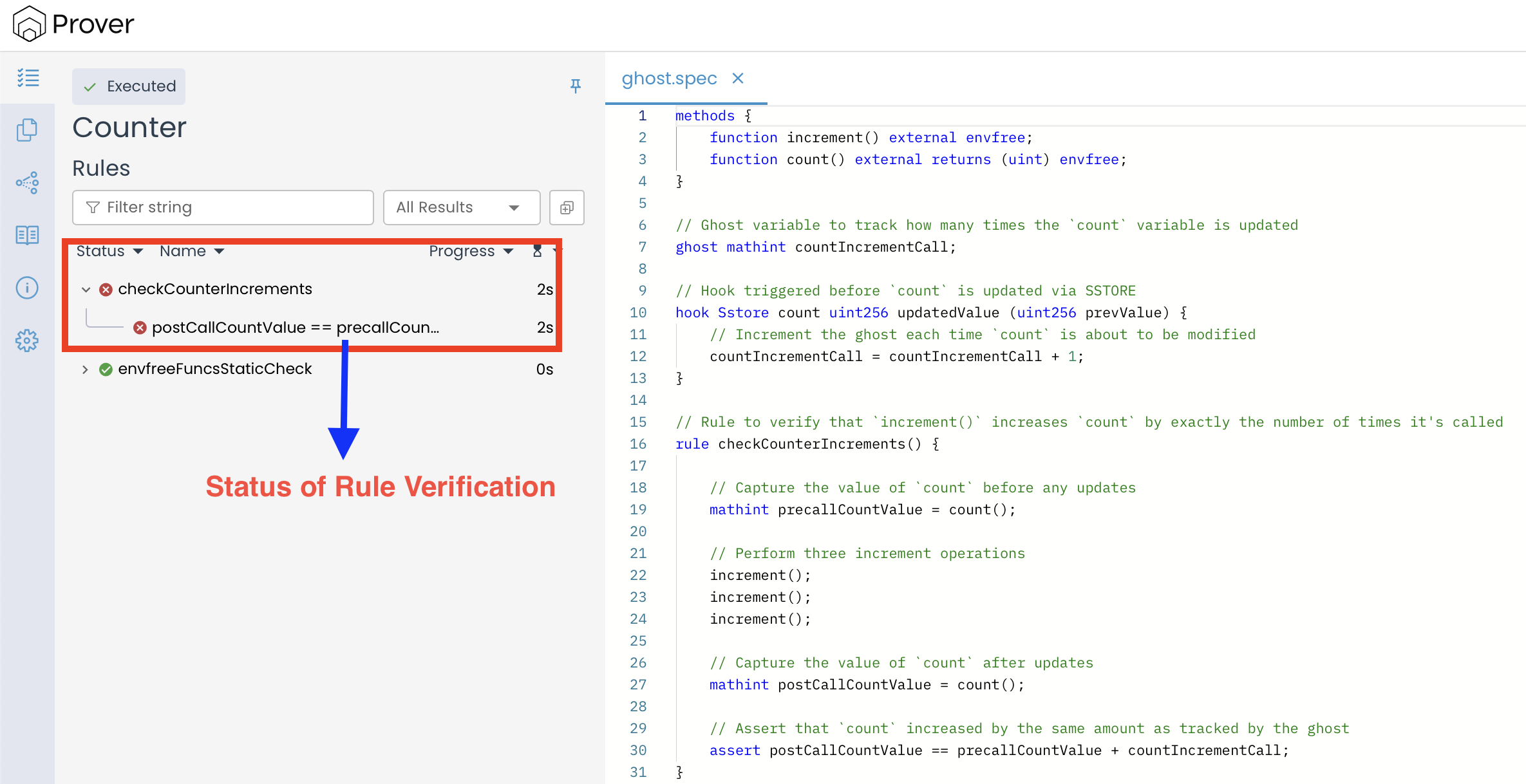

At first glance, this specification appears logically sound. However, when it is run through the Certora Prover, it fails to verify the checkCounterIncrements rule, as shown in the output illustrated below:

To understand why the assertion fails, let’s dig into the call trace provided by the Prover.

Why the Verification Failed

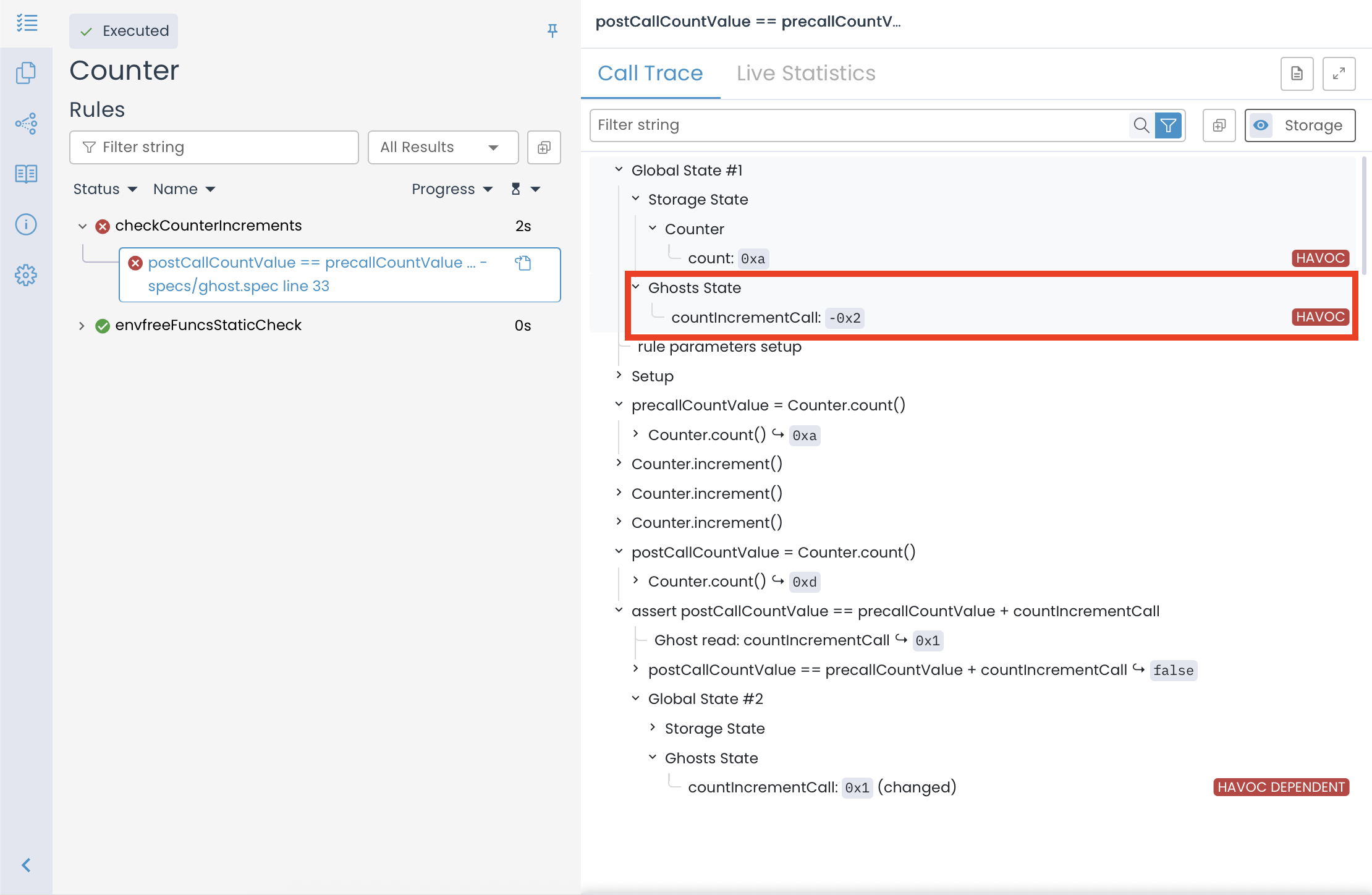

Our analysis of the call trace reveals that the rule failed not due to any flaw in logic, but because the ghost variable countIncrementCall began with a value chosen adversarially by the Prover, in this case -0x2 (or -2). Importantly, this value was not chosen by mistake. Instead, it was assigned intentionally through a systematic process known as havocing.

Havocing is the mechanism by which the Prover assigns arbitrary (unconstrained) initial values to state or ghost variables. “Arbitrary” here means that the variable is free to take any value within its type’s range. By doing so, the Prover can systematically examine edge cases and extreme scenarios that might cause a verification failure. This technique makes the verification process exhaustive, allowing the Prover to reason about all possible states the contract could reach.

In this particular case, the storage variable count started at 0xA (10 in decimal), while countIncrementCall started at -2. After calling increment() three times, count reached 0xD (13 in decimal), and the ghost variable increased from -2 to 1. However, the assertion expected:

postCallCountValue == precallCountValue + countIncrementCall;

which, substituting the actual values, became:

13 == 10 + 1

This is clearly false, hence the verification failed.

The “Lesson” to Remember

This failure highlights an important concept about how the Prover operates. During verification, the Prover does not assume any default or constructor-defined initial values for either contract storage or ghost variables. Instead, it havocs them — assigning arbitrary symbolic values within their allowed range. This behavior allows the Prover to reason about all possible starting states of the contract, ensuring that properties hold universally, not just for specific initial configurations.

While this approach makes verification exhaustive, it can also introduce unrealistic initial conditions. If a rule depends on a meaningful relationship between the contract’s storage and a ghost variable, havocing can break that relationship by starting them from unrelated values. For instance, a ghost that represents the number of increment() calls might begin with -2 or 5, even though no call to the increment() function has yet occurred.

When that happens, the rule might fail — not because its logic is flawed, but because the verification began from a state that could never exist in practice. Such failures are false positives: they highlight a mismatch between symbolic initialization and semantic intent rather than a real issue in the contract.

What’s the “Solution”

The key to avoiding these false failures is to ensure that the initial relationship between a ghost variable and the contract’s storage is logically correct before verification begins. This doesn’t mean fixing their exact values, but rather constraining them so they start in a state that makes sense.

For example, in our rule, the ghost variable countIncrementCall is meant to represent the number of times increment() has been invoked. At the start the rule, before any calls occur, this number must be zero. The contract’s count variable might start at any value — 0, 10, or 100 — but the ghost should always begin at 0, since no increments have yet happened.

To enforce such logical consistency, we use the require statement in CVL. In CVL, a require statement acts as a logical precondition, telling the Prover to explore all possible behaviors only from initial states that satisfy that specified relationship. By adding a simple constraint such as:

require countIncrementCall == 0;

We effectively filter out meaningless configurations where the ghost’s initial value contradicts its intended meaning.

With this constraint in place, the Prover still performs adversarial exploration, but it does so starting from semantically valid states. This ensures that any verification failure that occurs after applying the constraint corresponds to a real issue in the rule or the contract logic — not a side effect of arbitrary initialization.

Constraining the Ghosts with the require Statement

As discussed earlier, in our case, the ghost variable countIncrementCall is meant to represent the number of times the increment() function has been called. At the start of the rule’s execution, no such calls have occurred yet — meaning that the correct initial value for this ghost should be zero.

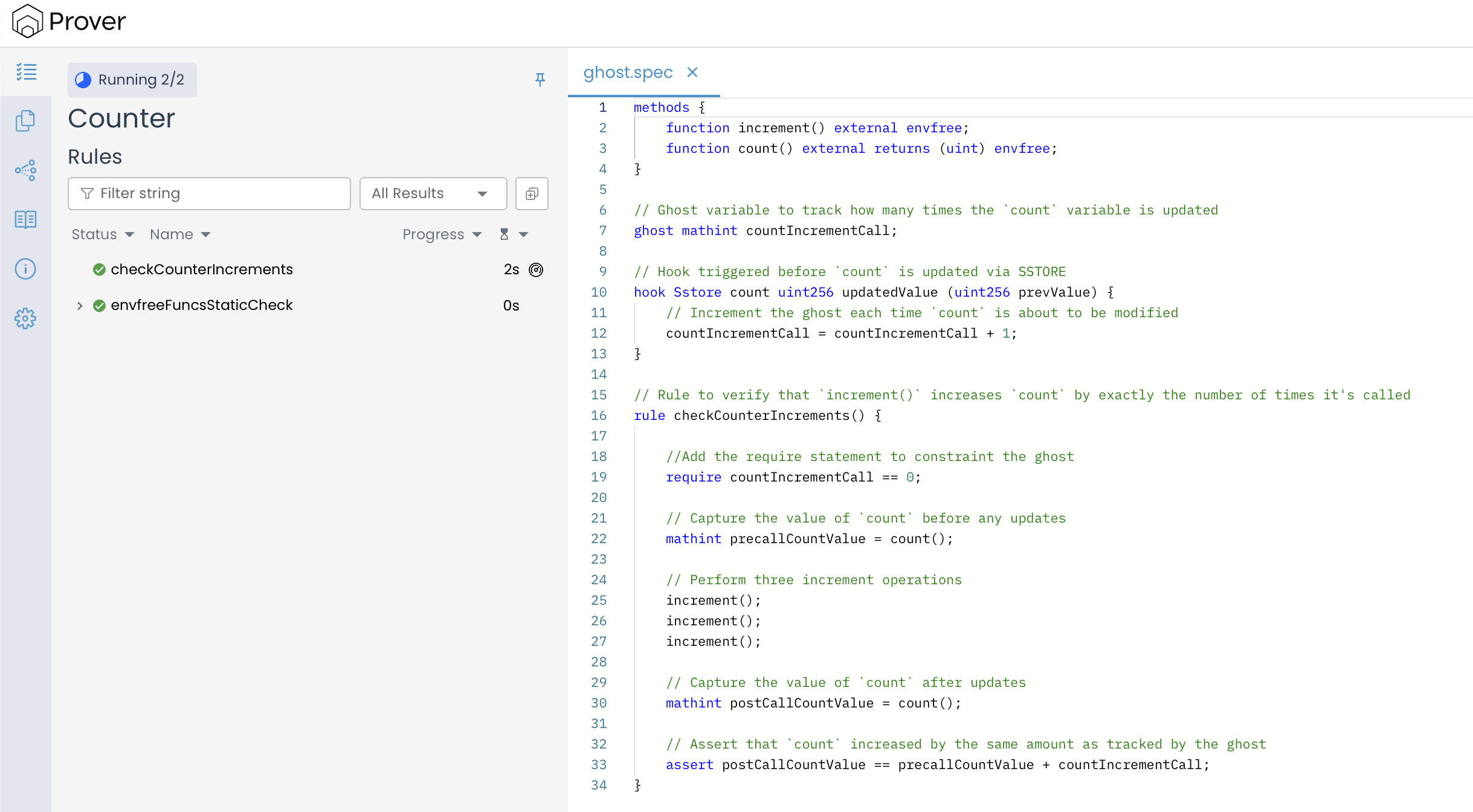

We can encode this constraint directly in our rule by simply adding require countIncrementCall == 0; at the beginning of the rule.

// Rule to verify that `increment()` increases `count` by exactly the number of times it's called

rule checkCounterIncrements() {

//Add the require statement to constrain the ghost

require countIncrementCall == 0;

// Capture the value of `count` before any updates

mathint precallCountValue = count();

// Perform three increment operations

increment();

increment();

increment();

// Capture the value of `count` after updates

mathint postCallCountValue = count();

// Assert that `count` increased by the same amount as tracked by the ghost

assert postCallCountValue == precallCountValue + countIncrementCall;

}

By including this precondition, we ensure that the Prover starts rule execution in a logically meaningful state, where the contract’s storage and the ghost’s semantics are aligned. The Prover still performs full symbolic and adversarial exploration, but it now avoids exploring impossible states such as the ghost variable countIncrementCall starting at -2 or 5.

When the verification is re-run, both count and countIncrementCall begin in logically consistent states. Their values might differ — for instance, count could start at 10 and countIncrementCall at 0 — yet their relationship remains sound.

From here on, every call to increment() updates both the contract’s storage and the ghost in perfect sync. After three calls, count increases by three, and countIncrementCall also records three updates. As a result, the assertion

assert postCallCountValue == precallCountValue + countIncrementCall;

holds across all valid execution paths, confirming that the rule now verifies successfully.

This demonstrates how a single line require countIncrementCall == 0 can eliminate false verification failures by anchoring the Prover’s analysis to a logically sound starting point. It doesn’t limit the scope of verification; instead, it ensures that the exploration space is semantically valid and that any rule failure reflects a genuine logical problem rather than an arbitrary initialization artifact.

However, there is one important assumption in this specification that deserves closer thought.

Here, the ghost countIncrementCall is incremented on writes to the count storage slot, which works because count is currently modified only inside increment(). But what if another function—say, reset() or setCount()—also modified count? The ghost would still increment, even though increment() wasn’t called.

This highlights an important design consideration: the choice of what to hook determines what the ghost actually tracks. In this case, we’re tracking storage writes, not function calls. For simple contracts, these may be equivalent—but as contracts grow more complex, that equivalence can break down. We’ll explore alternative hooking strategies that address this limitation in a later chapter.

Conclusion

Unconstrained ghost variables can lead the Prover to explore unrealistic states, resulting in misleading verification failures. By constraining their initial values using a require statement, we can make sure that ghosts start in a state that aligns logically with the contract’s storage. This small but crucial step keeps verification both exhaustive and semantically valid, allowing the Prover to report only genuine logical issues.