Introduction

The implication operator is frequently used as a substitute for the if statement since it is cleaner.

Consider the following example: a function mod(x, y) that takes two unsigned integers as parameters and returns x modulo y. The modulo operation computes the remainder of dividing x by y.

The Solidity implementation of this function is as follows:

/// Solidity

function mod(uint256 x, uint256 y) external pure returns (uint256) {

return x % y;

}

Suppose we want to formally verify the property: “if x < y, then the modulo must equal x." Using an if statement to express this in CVL causes a compilation error, since the final statement in a rule must be either an assert or a satisfy:

/// this rule will not compile

rule mod_ifXLessThanY_resultIsX_usingIf() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = mod(x, y);

if (x < y) {

assert result == x;

}

}

ERROR

: Failed to run Certora Prover locally. Please check the errors below for problems in the specifications (.spec files) or the prover_args defined in the .conf file.

CRITICAL

: [main] ERROR ALWAYS - Found errors in certora/specs/ImplicationOperator.spec:

CRITICAL

: [main] ERROR ALWAYS - Error in spec file (ImplicationOperator.spec:15:5): last statement of the rule mod_ifXLessThanY_resultIsX_usingIf is not an assert or satisfy command (but must be)

To resolve this, one workaround is to add a trivial assertion at the end:

if (P) {

assert Q;

}

assert true;

rule mod_ifXLessThanY_resultIsX_usingIf() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = mod(x, y);

if (x < y) {

assert result == x;

}

assert true; // trivially TRUE

}

However, this solution introduces a pointless assertion that clutters the specification. Another workaround is to use an if-else statement, where the else branch executes meaningful assertions:

if (P) {

assert Q;

} else {

assert (something_else);

}

rule mod_ifXLessThanY_resultIsX_usingIfElse() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = mod(x, y);

if (x < y) {

assert result == x;

} else {

assert result != x;

}

}

However, we weren’t originally interested in asserting that: “if x >= y, then result != x.” In many cases, like the one shown above, we are not interested in creating an assertion for every possible branch.

Implication (=>) In CVL

To handle this elegantly, we use the implication operator (=>). With implication, we can succinctly express conditions while avoiding the control flow complexity of if-else statements.

Thus, instead of writing if (P) assert Q (which doesn’t compile), we can equivalently use assert P => Q:

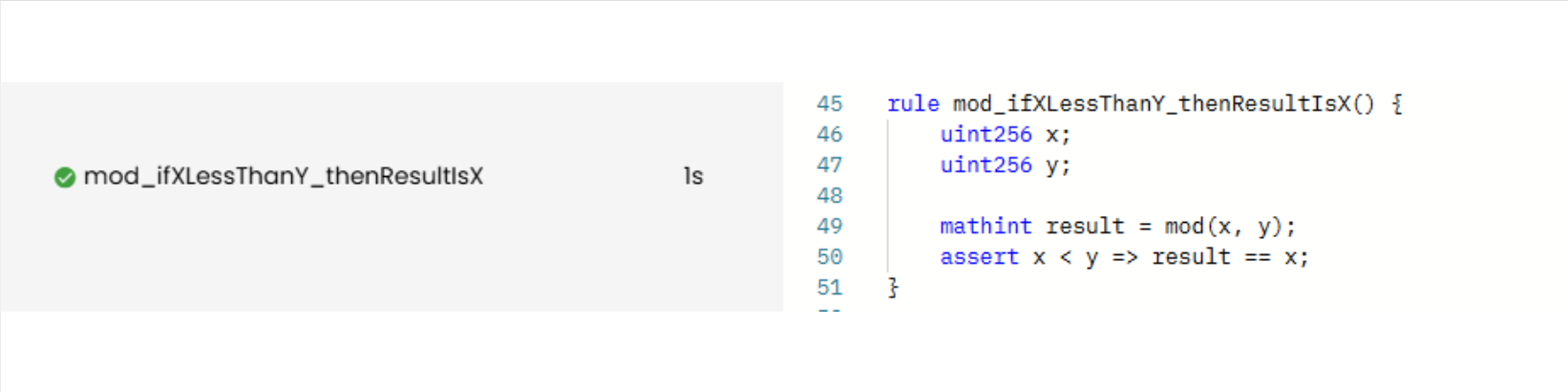

rule mod_ifXLessThanY_thenResultIsX() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = mod(x, y);

assert x < y => result == x;

}

Prove run: link

The form P => Q reads as “If P, then Q,” or simply, “P implies Q.” Note that Q => P is not necessarily equivalent, as we’ll see in the next section.

P Implies Q P => Q

Let’s take another example: Solady’s gas-optimized max function. As discussed in the previous chapter, it returns the greater of two inputs, x and y, defaulting to x if they are equal.

Below is the implementation, and as in the previous chapter, we’ve changed the visibility from internal to external to avoid the need for harnessing (which is beyond the scope of this chapter):

/// Solidity

function max(uint256 x, uint256 y) external pure returns (uint256 z) {

assembly {

z := xor(x, mul(xor(x, y), gt(y, x)))

}

}

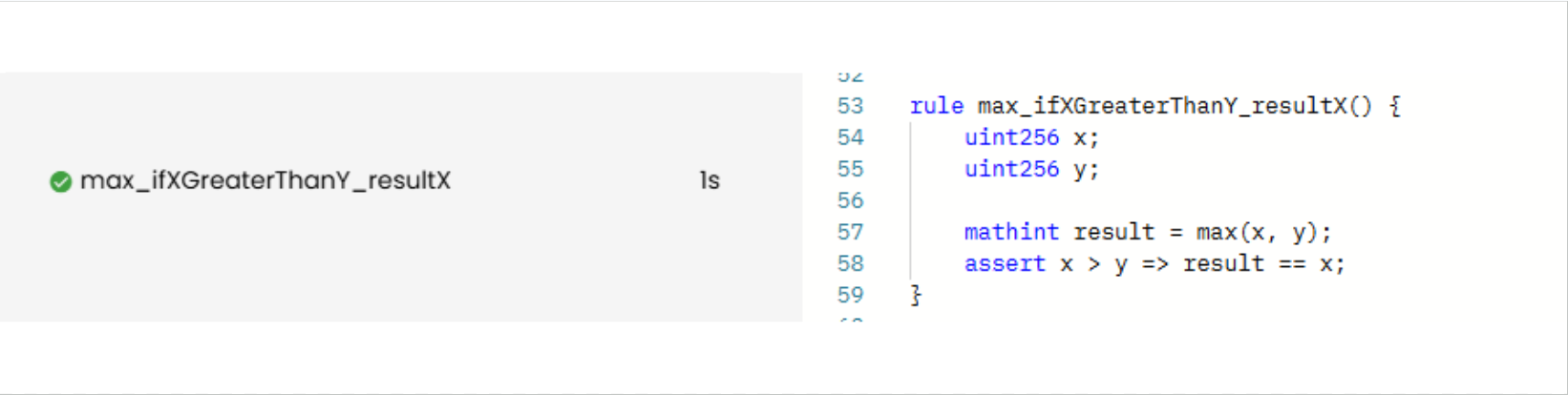

Let’s now formally verify the following property: “if x is greater than y, the return value of max(x, y) must be x.” We can express this in CVL as:

rule max_ifXGreaterThanY_resultX() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert x > y => result == x;

}

In this rule, the condition (x > y) and the expected outcome (result == x) form the implication P => Q. As expected, the property is VERIFIED.

Prover run: link

Note: The verification of the max function is not yet complete. We will cover that in the next section.

P => Q Is Not Equivalent To Q => P

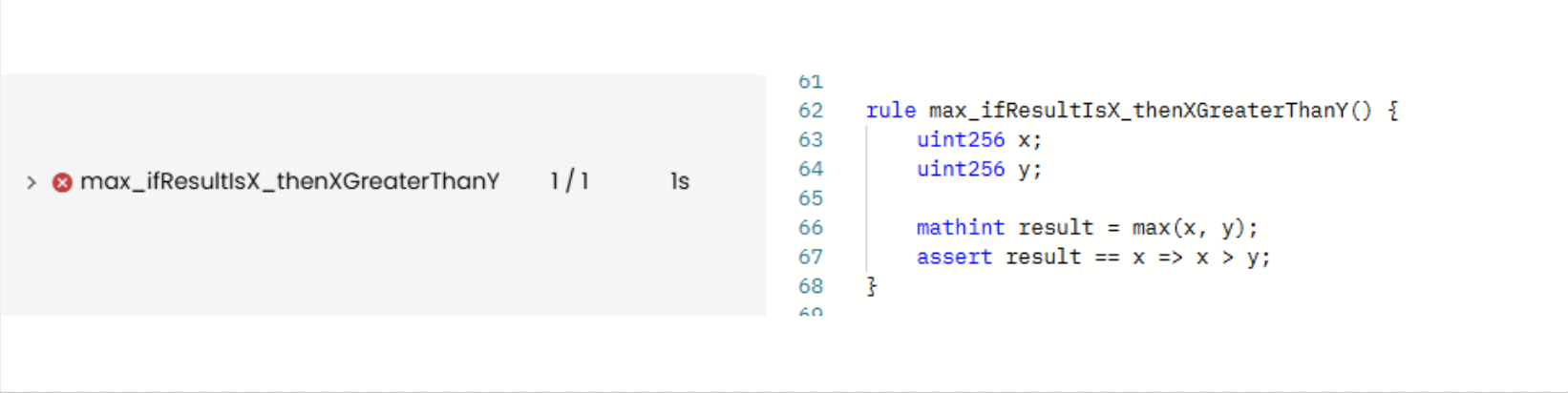

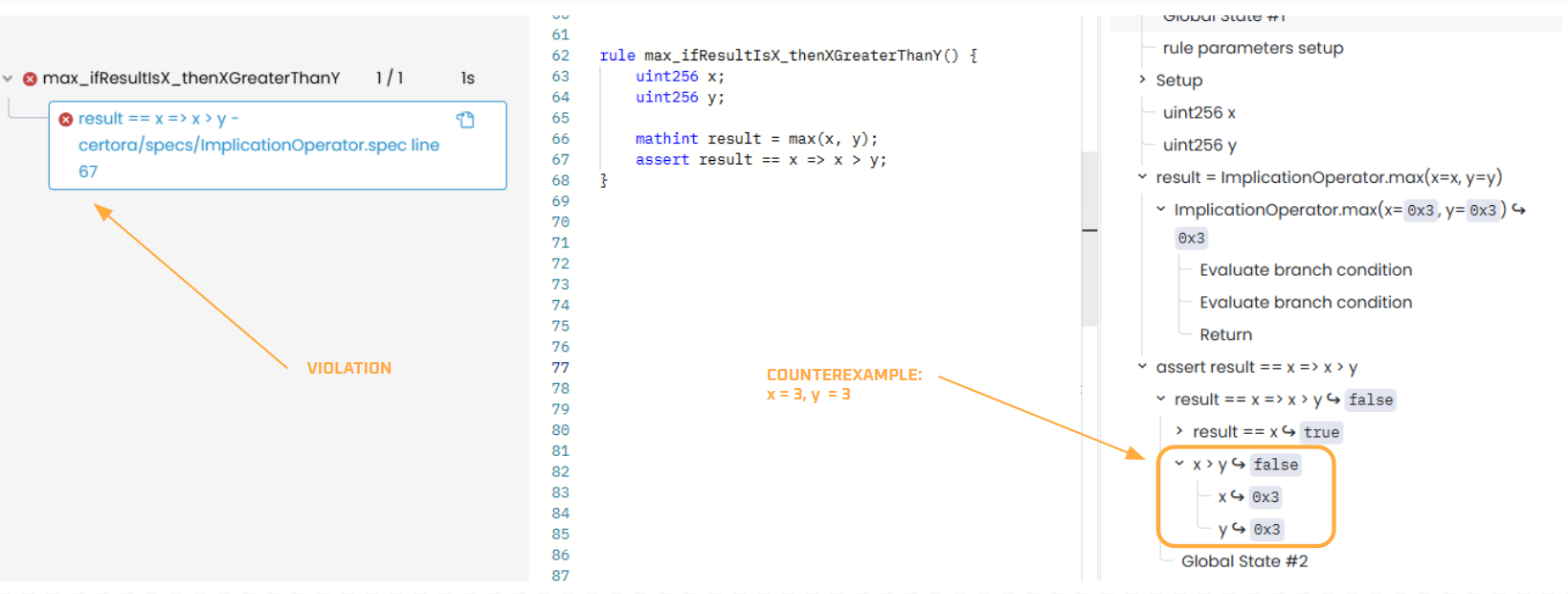

Now let’s consider the reverse implication: “if the return value of max(x, y) is x, then x > y” or result == x => x > y. This may seem valid at first; however, when x == y, the function still returns x. This contradicts the assertion that x > y, making the implication false in that case.

Here’s the rule that fails:

rule max_ifResultIsX_thenXGreaterThanY() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert result == x => x > y;

}

Counterexample

When a rule is violated, the Prover shows a counterexample. In this case, result == x not only happens when x > y — it also occurs when x == y. The counterexample specifically shows x = 3 and y = 3:

To fix this, we need to revise the condition to include all cases where result == x is valid: both when x > y and when x == y.

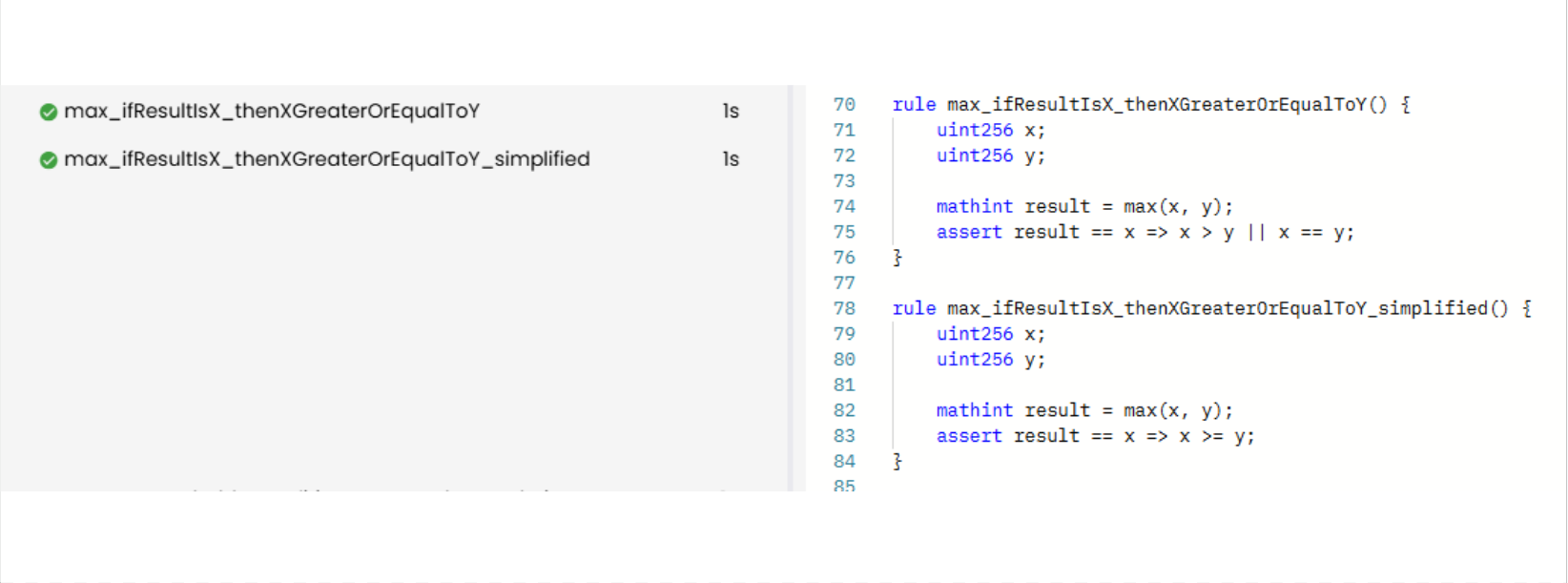

Here’s the revised rule, where || is the OR operator:

rule max_ifResultIsX_thenXGreaterOrEqualToY() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert result == x => x > y || x == y;

}

or, more simply:

rule max_ifResultIsX_thenXGreaterOrEqualToY_simplified() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert result == x => x >= y;

}

And now it’s VERIFIED:

Prover run: link

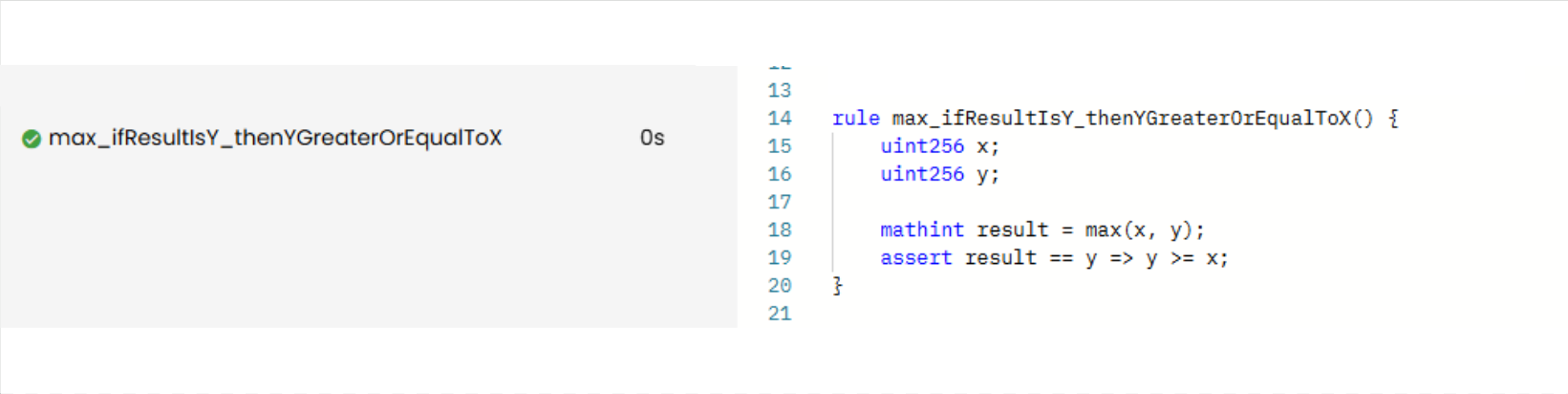

Now, to complete the verification, we will also verify the property that max(x, y) returns y when y is greater than or equal to x. Here’s the rule:

rule max_ifResultIsY_thenYGreaterOrEqualToX() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert result == y => y >= x;

}

As expected, it is VERIFIED:

Prover run: link

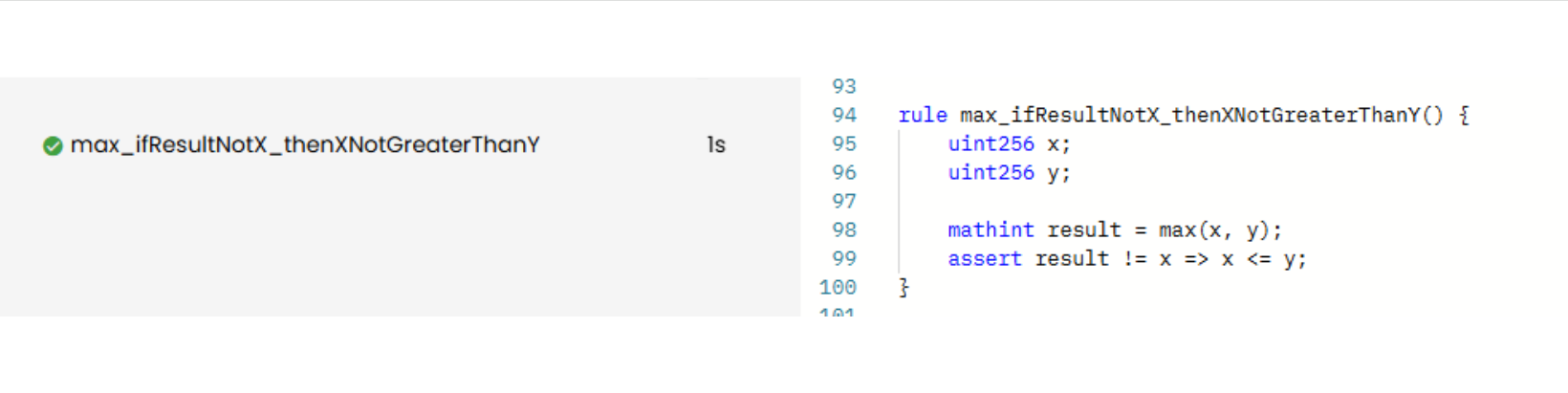

P => Q Is Equivalent to !Q => !P

Rewriting an implication P => Q into its contrapositive form !Q => !P suggests an alternative way to think about a specification.

Let’s revisit our previous rule with the assertion: x > y => result == x:

rule max_ifXGreaterThanY_resultX() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert x > y => result == x;

}

In its original form, this rule is concerned with what happens when x is greater than y, which is that the return value of max(x, y) is x.

In the contrapositive form, assert !(result == x) => !(x > y), we are instead concerned with what happens if the return value of max(x, y) is not x. In that case, we expect that x is not greater than y (or simply, x <= y):

rule max_ifResultNotX_thenXNotGreaterThanY() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert result != x => x <= y;

}

Prover run: link

Both forms express the same logical truth, but from different perspectives.

To better understand this, let’s use a common analogy:

- “If it rained, the ground is wet,” or

hasRained => isGroundWet

Its contrapositive is:

- “If the ground is not wet, then it definitely didn’t rain,” or

!isGroundWet => !hasRained

However, the fact that it has not rained does not guarantee that the ground is not wet. Someone could have poured water on it. Therefore, !hasRained => !isGroundWet is not logically valid.

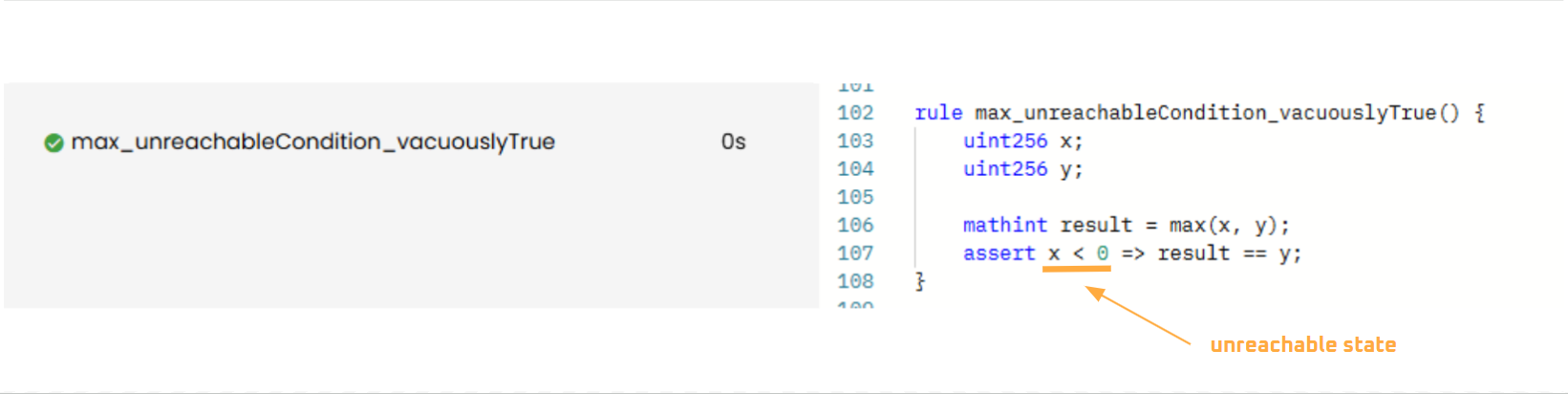

Vacuous Truth and Tautology In Implication

Now that we understand how implication works, we must also be cautious when writing these statements. We might unknowingly write implications with false assurances, a topic we’ll explore next.

When P is always FALSE, P => Q is TRUE regardless of Q (vacuous)

An implication becomes vacuously true when the condition (P) is unreachable (always false), meaning there’s no possible state where P holds. In such cases, the entire statement P => Q is automatically considered true, regardless of what the outcome (Q) is.

This happens because if P can never be true, then there is no instance in which the implication can be violated. Hence, no counterexample exists.

Let’s use this example: “if x < 0, then result == y.” Since x is a uint256, it can never be negative. That makes x < 0 an unreachable state. No matter what we assert on the right-hand side (Q), the implication will always verify.

Here’s the CVL vacuous rule:

rule max_unreachableCondition_vacuouslyTrue() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert x < 0 => result == y;

}

This rule is VERIFIED, but not because x < 0 leads to result == y. It verifies only because x < 0 is unreachable in any valid execution path, making the implication vacuously true. It confirms that no counterexample exists because the condition can never happen:

Prover run: link

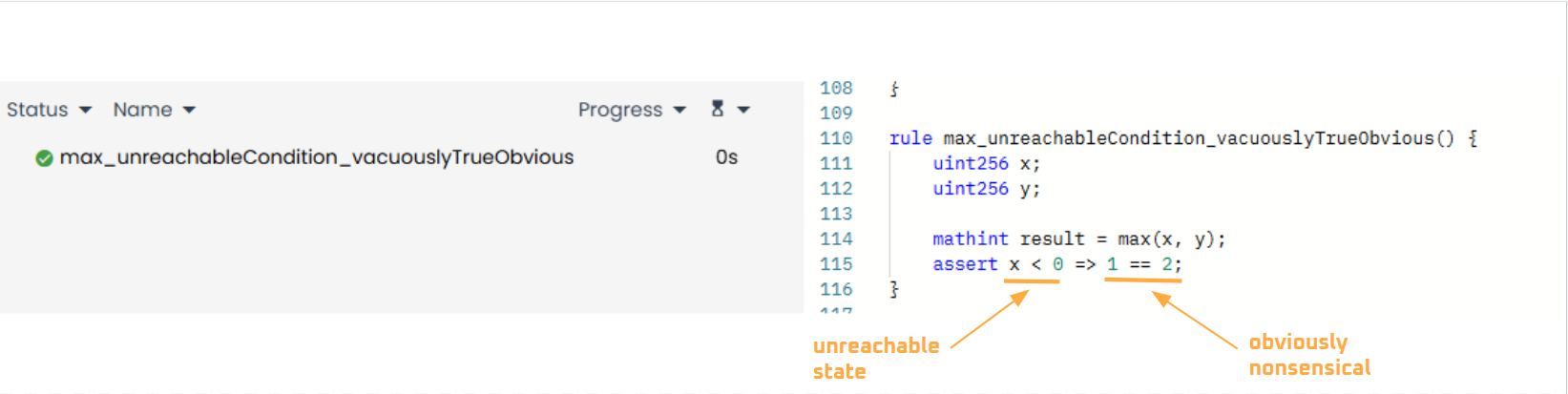

Since the condition (P) can never occur, the outcome (Q) can be anything — even something nonsensical like 1 == 2, as shown below:

rule max_unreachableCondition_vacuouslyTrueObvious() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert x < 0 => 1 == 2;

}

Prover run: link

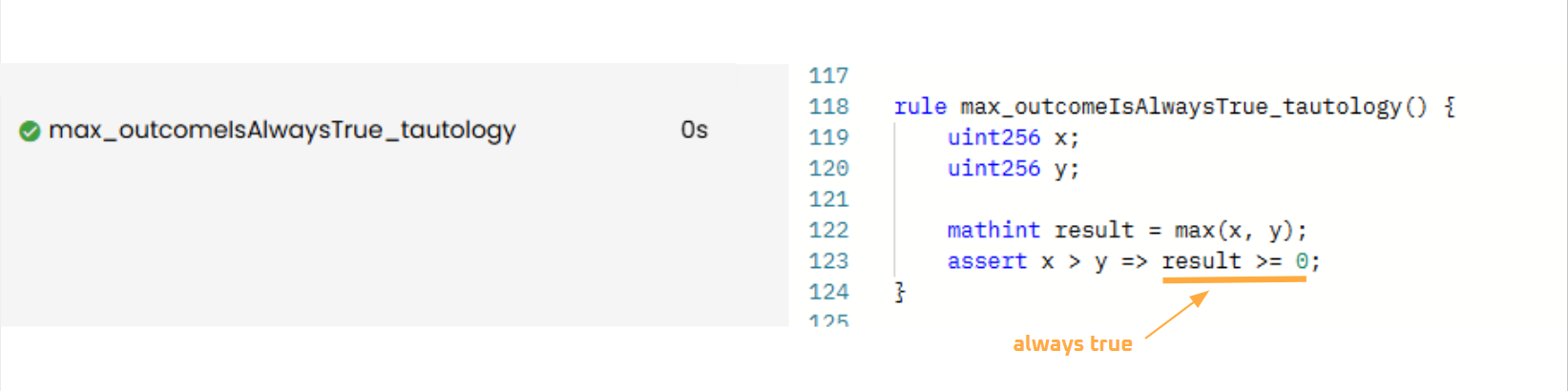

When Q is always TRUE_,_ P => Q is TRUE regardless of P (tautology)

An implication becomes tautologically true when the outcome (Q) is always true, regardless of the condition (P). In such cases, the entire statement P => Q is automatically considered true, even if the condition is irrelevant or misleading.

This happens because if Q is always true, the outcome is guaranteed; hence, the implication can never be false.

Let’s use this example: “if x > y, then result >= 0.”

At first glance, this seems to imply that x > y guarantees a non-negative result. But result is a uint256, which is always greater than or equal to zero by type. So the expression result >= 0 is always true.

Here’s the CVL tautological rule:

rule max_outcomeIsAlwaysTrue_tautology() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint result = max(x, y);

assert x > y => result >= 0;

}

This rule is VERIFIED, not because x > y leads to result >= 0, but because result >= 0 is always true by type, making the implication tautologically true:

Prover run: link

Formally Verifying Solmate’s mulDivUp()

Now that we know the fundamentals, we’re formally verifying Solmate’s mulDivUp() using the implication operator. As the name suggests, this function multiplies two unsigned integers, divides the result by another unsigned integer, and rounds up if there is a remainder. If there is no remainder, it simply returns the quotient.

The properties we’ll formally verify fall into two categories: rounding behavior and revert behavior. But before we do that, we will make a small adjustment to the original mulDivUp() code.

The Solmate’s mulDivUp() function has internal visibility, and we will change it to external for convenience. Otherwise, setting up a harness contract would be necessary, which is beyond the scope of this chapter and may introduce unnecessary mental overhead at this point.

Here’s the mulDivUp() function:

/// Solidity

uint256 internal constant MAX_UINT256 = 2**256 - 1;

function mulDivUp(

uint256 x,

uint256 y,

uint256 denominator

) external pure returns (uint256 z) {

assembly {

// Equivalent to require(denominator != 0 && (y == 0 || x <= type(uint256).max / y))

if iszero(mul(denominator, iszero(mul(y, gt(x, div(MAX_UINT256, y)))))) {

revert(0, 0)

}

// If x * y modulo the denominator is strictly greater than 0,

// 1 is added to round up the division of x * y by the denominator.

z := add(gt(mod(mul(x, y), denominator), 0), div(mul(x, y), denominator))

}

}

The assembly code explanation is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, the comments help us understand what the code is doing.

These lines below,

// Equivalent to require(denominator != 0 && (y == 0 || x <= type(uint256).max / y))

if iszero(mul(denominator, iszero(mul(y, gt(x, div(MAX_UINT256, y)))))) {

revert(0, 0)

}

as the comment suggests, represent a require statement that enforces the following conditions:

denominator != 0, which prevents division by zero, as division by zero is not allowed.y == 0 || x <= type(uint256).max / y, meaning:- If

y == 0, the condition holds becausex * ynaturally evaluates to0. In this case, an overflow check is unnecessary. - Otherwise, if

y != 0,xmust be less than or equal totype(uint256).max / ymaking sure thatx * ydoes not exceedtype(uint256).max, preventing overflow.

- If

Now we conclude that the properties to be formally verified are the following:

- If

denominator == 0, then function reverts. - If

x * y > MAX_UINT256, then function reverts.

In the next line,

// If x * y modulo the denominator is strictly greater than 0,

// 1 is added to round up the division of x * y by the denominator.

z := add(gt(mod(mul(x, y), denominator), 0), div(mul(x, y), denominator))

as the comment suggests, the function handles rounding as follows:

- If

x * y % denominator > 0,1is added tox * y / denominatorto compensate for Solidity’s truncation in integer division. Since Solidity rounds down, adding1effectively rounds up the value. - If

x * y % denominator == 0, no rounding adjustment is needed, and the result is returned as is.

Now we conclude that the properties to be formally verified are the following:

- If

x * y % denominator > 0, then the result isx * y / denominator + 1. - If

x * y % denominator == 0, then the result isx * y / denominator.

Since we now understand how the function works and what properties to formally verify, we can proceed with writing the rules. Let’s start with the rules for rounding behavior.

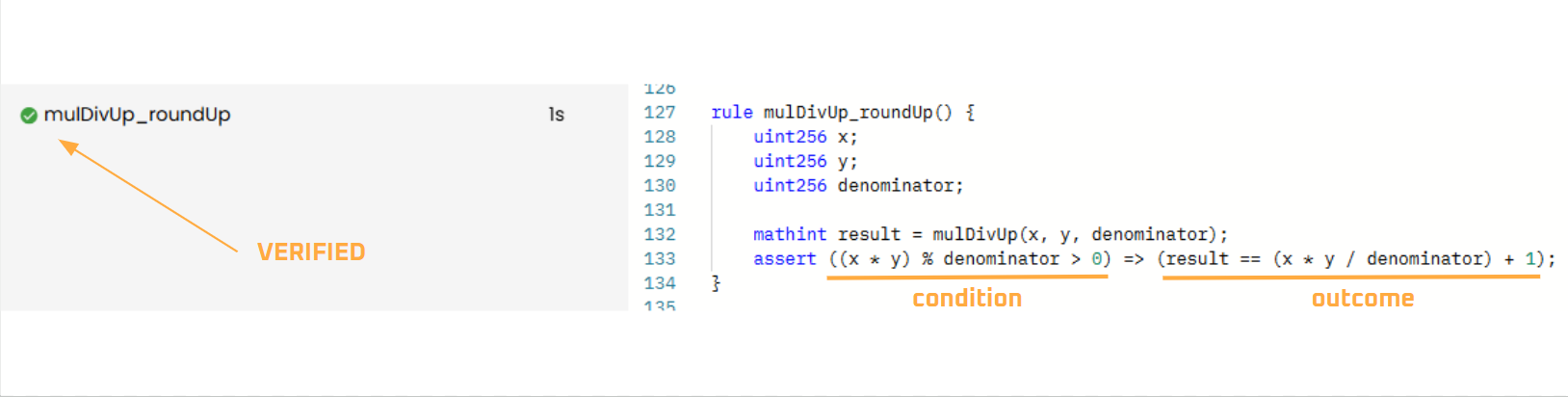

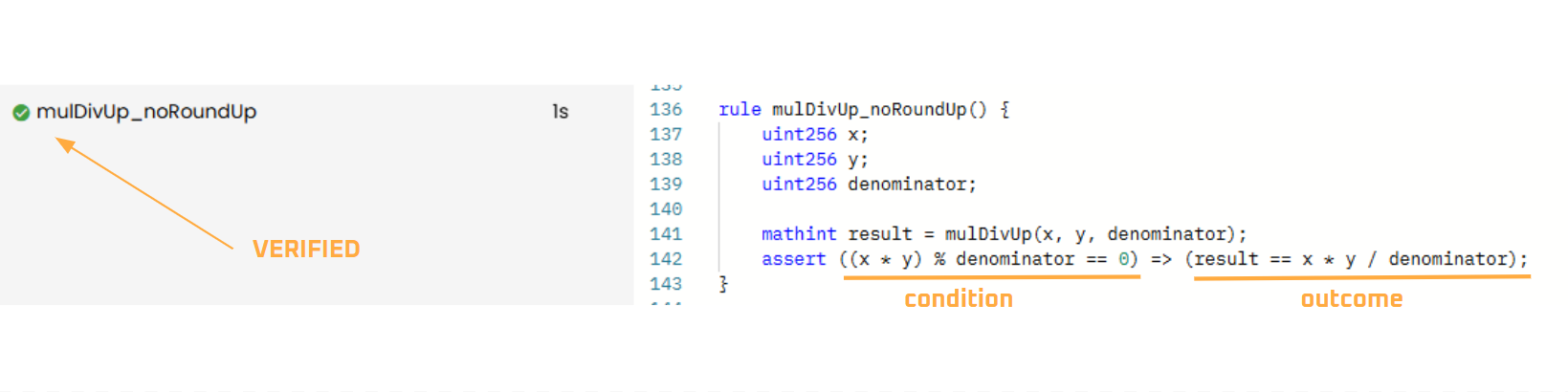

Rounding Behavior

Below is the CVL rule specification for the rounding behavior property.

The assertion of the rule mulDivUp_roundUp() states that when the product of x and y is divided by the denominator and has a remainder, the result is incremented by 1.

Similarly, the assertion in the rule mulDivUp_noRoundUp() states that when the product of x and y is divided by the denominator and has no remainder, the result is returned as is.

As expected, these rules are VERIFIED:

rule mulDivUp_roundUp() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mathint result = mulDivUp(x, y, denominator);

assert ((x * y) % denominator > 0) => (result == (x * y / denominator) + 1);

}

rule mulDivUp_noRoundUp() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mathint result = mulDivUp(x, y, denominator);

assert ((x * y) % denominator == 0) => (result == x * y / denominator);

}

Prover run: link

Now, let’s move on to the next category of properties for this function: revert behavior.

Revert Behavior

As previously discussed, there are two cases where mulDivUp() reverts:

- If

denominator == 0 - If

x * y > MAX_UINT256

When formally verifying reverts, we must include the @withrevert tag when invoking functions. By default, the Prover executes only non-reverting paths, meaning all arguments passed to mulDivUp(x, y, denominator) are non-reverting. However, adding @withrevert to the function instructs the Prover to also consider arguments that cause a revert. This allows us to account for reverting cases in our implication statements.

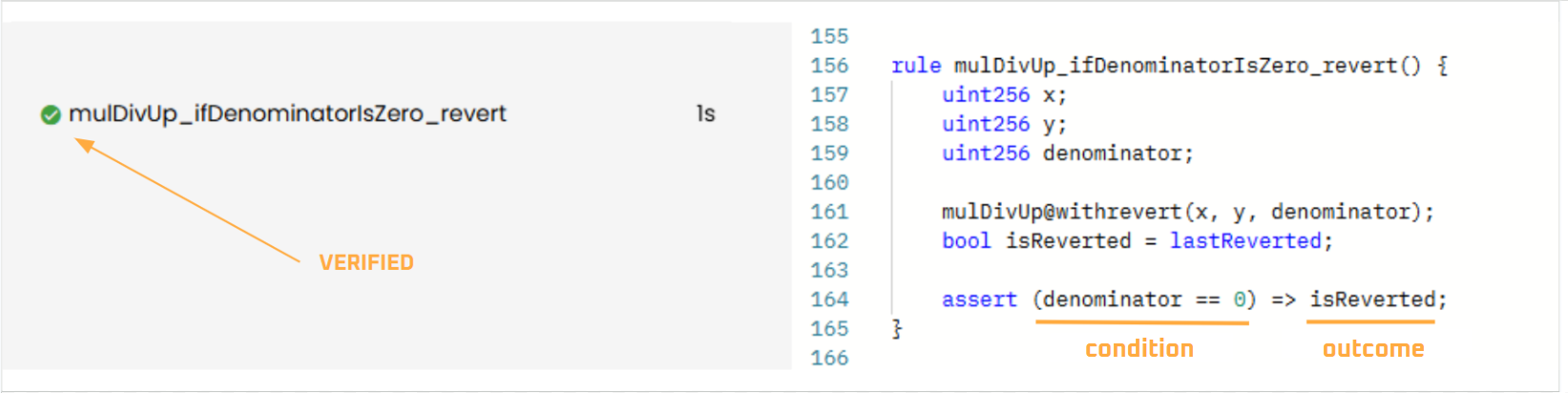

Below is the CVL rule specification:

rule mulDivUp_ifDenominatorIsZero_revert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

bool isReverted = lastReverted;

assert (denominator == 0) => isReverted;

}

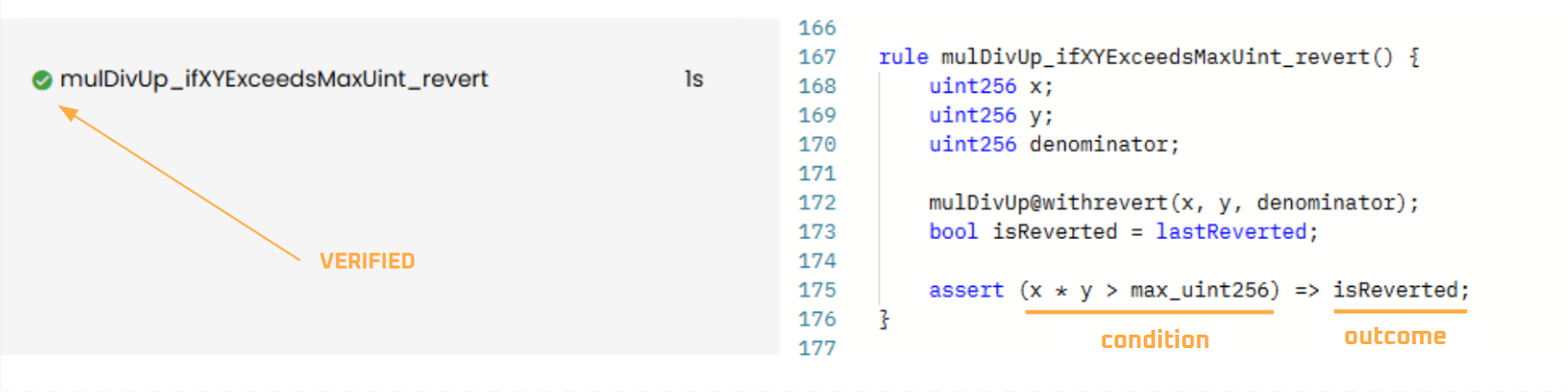

rule mulDivUp_ifXYExceedsMaxUint_revert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

bool isReverted = lastReverted;

assert (x * y > max_uint256) => isReverted;

}

As expected, these rules are VERIFIED:

Prover run: link

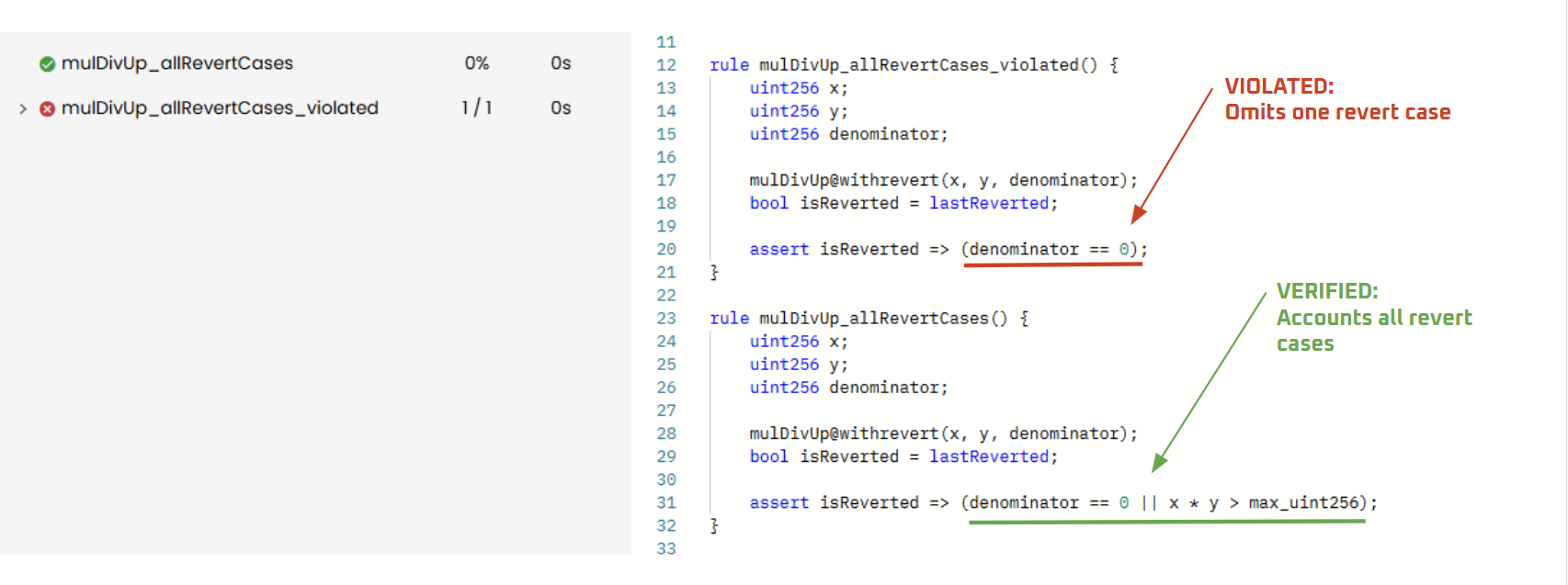

There’s an even more interesting approach to this. So far, we’ve used the P => Q construct, which means (P) condition result in (Q) outcome. But if we reverse it to Q => P, it means (Q) outcome results from (P) conditions; therefore, we must account for all possible cases of P leading to Q.

Below is the implementation where, in the first rule, we intentionally omit one revert case, while in the second rule, we account for all cases. As a result, the first rule results in a VIOLATION, while the second rule is VERIFIED:

rule mulDivUp_allRevertCases_violated() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

bool isReverted = lastReverted;

assert isReverted => (denominator == 0);

}

rule mulDivUp_allRevertCases() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

bool isReverted = lastReverted;

assert isReverted => (denominator == 0 || x * y > max_uint256);

}

Prover run: link

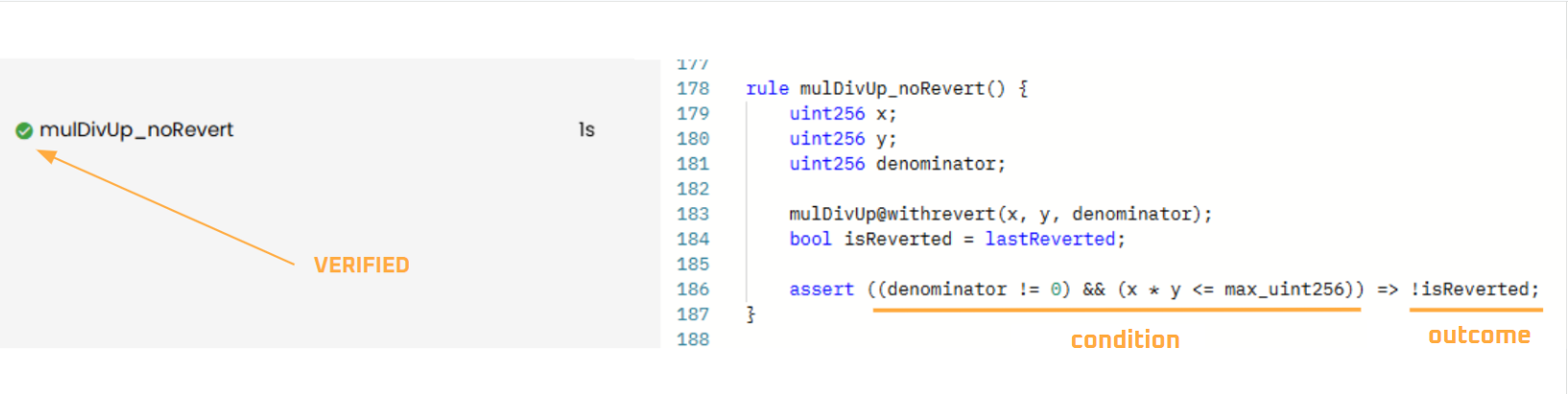

In the next sub-section, we’ll formally verify non-reverts, an optional step since we’ve covered all revert cases. However, we’ll still do it as it may have future use cases.

Non-Revert Behavior (Optional)

If we can formally verify reverting paths, we can also verify non-reverting ones. To do so, we need to reframe the statements as:

denominator != 0x * y <= MAX_UINT256

and combine them as shown in the CVL rule implementation below:

rule mulDivUp_noRevert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

bool isReverted = lastReverted;

assert ((denominator != 0) && (x * y <= max_uint256)) => !isReverted;

}

As expected, the rule is VERIFIED:

Prover run: link

Summary

- An implication statement consists of a condition

P, an outcomeQ, and the implication operator (=>). - The implication operator defines a one-way conditional relationship, meaning

P => Qdoes not implyQ => P. P => Qand its contrapositive!Q => !Pare logically equivalent but offer different perspectives, shifting focus from when the condition holds to when it does not.- For an implication to be meaningful (neither vacuous nor tautological),

Q(the outcome) must depend onP(the condition) being true. - A vacuous truth occurs when

Pis unreachable (always false), makingP => Qtrue regardless ofQdue to the lack of counterexamples. - A tautology occurs when

Qis always true, makingP => Qtrue regardless ofP. - Vacuous truths and tautologies create misleading assurance in formal verification.

Exercises for the reader

- Formally verify Solady min always returns the min.

- Formally verify Solady zeroFloorSub returns

max(0, x - y). In other words, ifxis less thany, it returns0. Otherwise, it returnsx - y.