Loops are one of the most common programming constructs, but they remain challenging to reason about in formal verification. While a loop in Solidity or any other programming language appears simple—merely repeating an action until a condition is met—its verification becomes exponentially complex. A formal verification engine, such as the Certora Prover, must reason about all possible numbers of loop iterations, which leads to what is known as the path explosion problem: the exponential increase in possible execution paths that the Prover must explore as the number of loop iterations or conditional branches increases.

To manage this complexity, the Certora Prover and other formal verification tools use a technique called bounded loop unrolling. This technique limits how many times a loop is symbolically explored during verification, allowing the Prover to avoid an otherwise infeasible search space caused by unknown and unbounded loop iterations.

In this chapter, we will:

- Explain why loops are difficult to verify and how the path explosion problem arises.

- Show how the Prover mitigates this issue using bounded loop unrolling.

- Introduce two configuration flags,

--loop_iterand--optimistic_loop, that control how loops are explored. - Discuss the strengths and limitations of these approaches, and why they cannot provide a complete and sound proof for unknown and unbounded loops.

Why Loops Are Hard to Verify

To understand why loops are difficult to verify, consider the following Solidity contract that keeps track of the largest number added to a collection array:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract MaxInCollection {

uint256[] collection;

uint256 public maxInCollection = 0;

function addToCollection(uint256 x) public {

if (x > maxInCollection) {

maxInCollection = x;

}

collection.push(x);

}

function returnMax() public view returns (uint256) {

uint256 maxTmp = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < collection.length; i++) {

if (collection[i] > maxTmp) {

maxTmp = collection[i];

}

}

return maxTmp;

}

}

In the above contract, the function addToCollection() appends a new element to the collection array. It also updates the maxInCollection state variable whenever the new element exceeds the current maximum. The contract also includes returnMax(), which iterates through the array to compute and return the maximum value.

The core property (invariant) this contract should uphold is simple: maxInCollection should always equal the value returned by returnMax().

Let’s formally verify this by expressing it as an invariant in CVL:

methods {

function maxInCollection() external returns(uint256) envfree;

function returnMax() external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

invariant maxEqReturnMax()

maxInCollection() == returnMax();

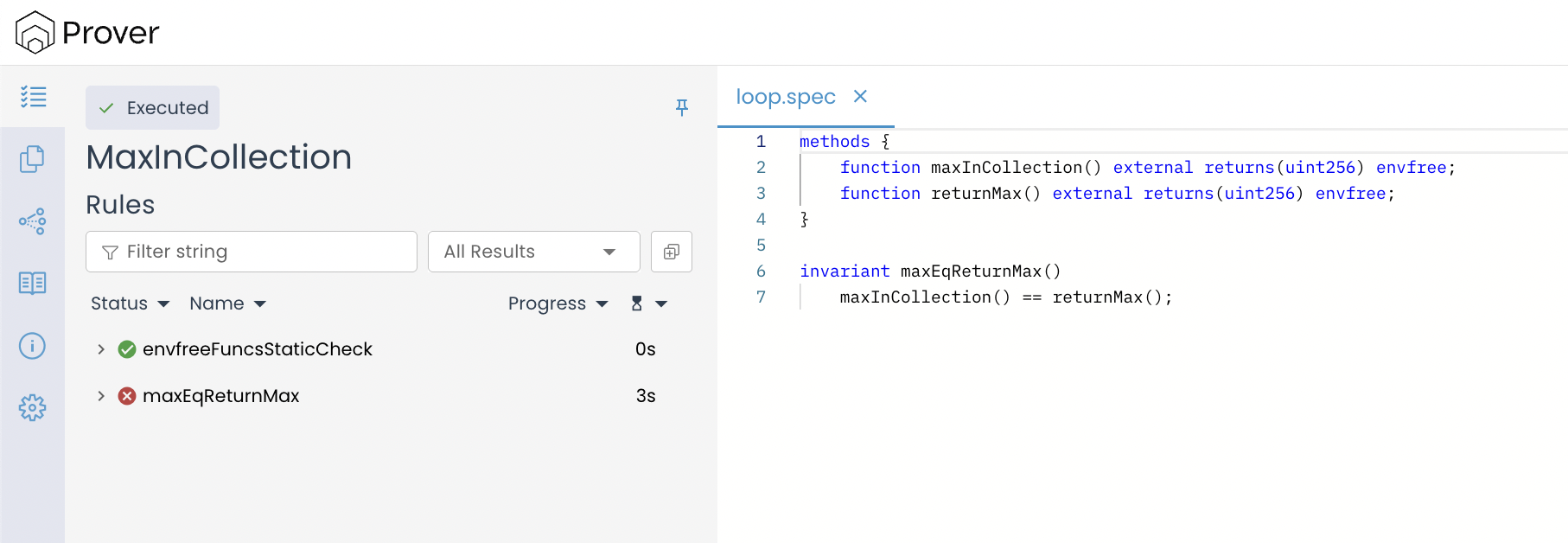

At first glance, this claim appears valid and we expect the Prover to verify it successfully. However, when we run it through the Certora Prover, the verification fails, as shown below:

After seeing the verification result, you might be puzzled: if both functions are logically equivalent in what they return, why does the Prover still fail to establish that equivalence?

The answer lies in the fundamental difference between how the EVM executes a program and how the Prover reasons about it: the EVM executes one specific path with concrete inputs, whereas the Prover explores all possible paths with symbolic inputs.

To understand this difference, let’s first examine what happens during contract execution, then contrast it with how the Prover reasons symbolically.

A Program Follows One Concrete Path

When we execute this contract in practice with concrete inputs (specific, actual values), the program follows a single, concrete path determined by these inputs and the sequence of function calls.

For example:

- Suppose we call

addToCollection(7),addToCollection(5), andaddToCollection(9)in that order. - The array collection becomes

[7, 5, 9], andmaxInCollectionis updated to 9. - When we later call

returnMax(), the function iterates over the array three times and computes the maximum value 9. - Both

maxInCollectionandreturnMax()therefore return the same result, confirming that the maximum value is correctly tracked.

So in concrete execution, the program follows a single, deterministic path defined by the given inputs and array contents, and both functions return the same value.

The Prover Reasons About All Inputs at Once

The Certora Prover is a symbolic execution engine, meaning it doesn’t test the program on one input at a time. Instead, it reasons about all possible executions simultaneously.

To achieve this, the Prover symbolically simulates the program’s behavior step by step, reasoning over logical constraints instead of concrete values.

Here’s how the Prover tackles the invariant maxEqReturnMax(), step-by-step:

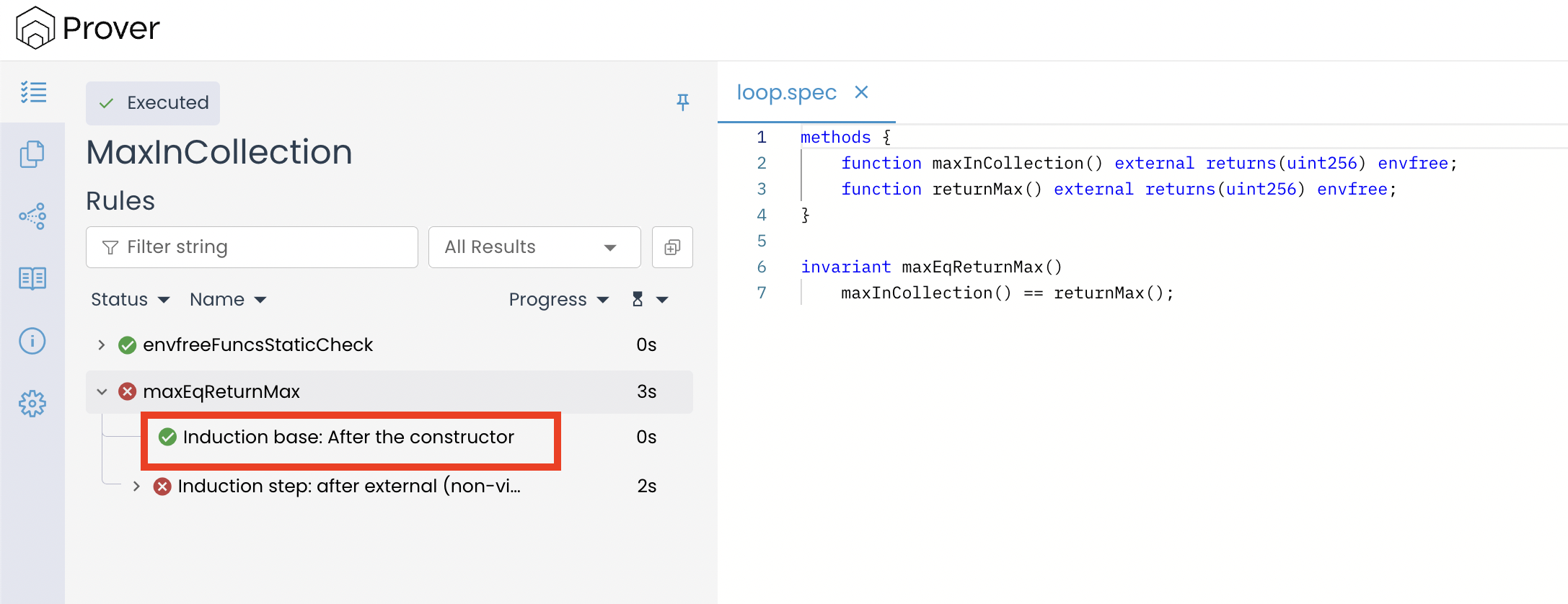

- Initial State Check (Base Case): The first step is to check whether the invariant holds immediately after the contract’s constructor finishes executing.

- In this state, the

collectionarray is empty, socollection.lengthis0. - The

maxInCollectionstate variable is initialized to0. - The Prover then symbolically executes the

returnMax()function. It initializesmaxTmpto 0 and encounters the loop:

- In this state, the

for (uint256 i = 0; i < collection.length; i++)

Since collection.length is 0 in the initial state, the loop body never runs, and the function simply returns maxTmp, which remains 0.

As a result, the invariant holds in the initial state, meaning the base case is successfully verified, as shown below:

-

The Inductive Step: After confirming that the invariant holds in the initial state, the Prover moves to the next phase — the inductive step. This step is about ensuring that the invariant continues to hold after any state change in the contract.

In simple terms, the Prover checks the following:

“If the invariant holds in the current state S, then it must also hold in the next state S′ that results from any valid function call.”

To reason about this, the Prover conceptually follows three stages:

a. Before the Call Assumption: The Prover begins by considering an arbitrary, valid state

Sin which the invariant already holds. This forms the inductive hypothesis, a standard step in inductive reasoning. The Prover doesn’t need to know the actual contents of thecollectionarray or the value ofmaxInCollection; it assumes—as part of the proof method itself—that in this stateS, the propertymaxInCollection() == returnMax()is true.b. Symbolic Execution: Next, the Prover simulates a function call that could change the contract’s state. In our case, it picks

addToCollection(). Crucially, it does not choose a specific value like5or10as input toaddToCollection(). Instead, it uses a symbolic variable, x, which represents any possibleuint256value that the function could receive.The Prover then symbolically executes the body of

addToCollection(x):-

It sees the

ifstatement:if (x > maxInCollection). Since bothxandmaxInCollectionare symbolic, the Prover branches, considering both possibilities:Case 1:

x > maxInCollection. The new stateS'will havemaxInCollectionupdated tox.Case 2:

x <= maxInCollection. The new stateS'will havemaxInCollectionunchanged.

In both cases, it symbolically executes

collection.push(x). This means thecollectionarray in stateS'is now thecollectionfrom stateSplus the new elementx, andcollection.lengthhas increased by 1.The Prover now has a complete symbolic description of the new state,

S', in terms of the old stateSand the symbolic inputx.c. After Call Verification: In the final step, the Prover must now prove that the invariant holds in the new state

S'. It asks: IsmaxInCollection()(in state S’) ==returnMax()(in state S’)?To complete this step, the Prover analyzes both sides of this equation:

-

LHS (

maxInCollection()): This is straightforward. The Prover knows the new value ofmaxInCollectionsymbolically (it’s either the old value orx). -

RHS (

returnMax()): Next, it will symbolically execute thereturnMax()function. This is the point where verification becomes challenging, becausereturnMax()contains a loop:

-

for (uint256 i = 0; i < collection.length; i++) {...}

Why is the Loop an Issue?

When the Prover reaches the returnMax() function, it needs to symbolically execute the loop:

for (uint256 i = 0; i < collection.length; i++) {...}

In concrete execution, the loop runs a specific number of times — once for each element in the array.

But for the Certora Prover, the array length is symbolic, so the number of iterations is unknown.

This is the critical point: the Prover must consider all possible array lengths at once, from an empty array to the maximum representable size. That alone already creates a huge search space.

Inside the loop, there is another conditional:

if (collection[i] > maxTmp)

For symbolic inputs, this condition may be true or false in each iteration.

So every iteration doubles the number of symbolic paths the Prover must consider.

If the array length is n, the Prover faces roughly 2ⁿ paths.

For example:

- 2 elements ⇒ 4 paths (2²)

- 3 elements ⇒ 8 paths (2³)

- 10 elements ⇒ 1024 paths (2¹⁰)

- For a symbolic (unbounded) length → effectively unmanageable

This exponential growth is what makes it practically infeasible for the Prover to explore all paths within reasonable time or resources.

The Prover’s Approach to Tackling the Path Explosion Problem

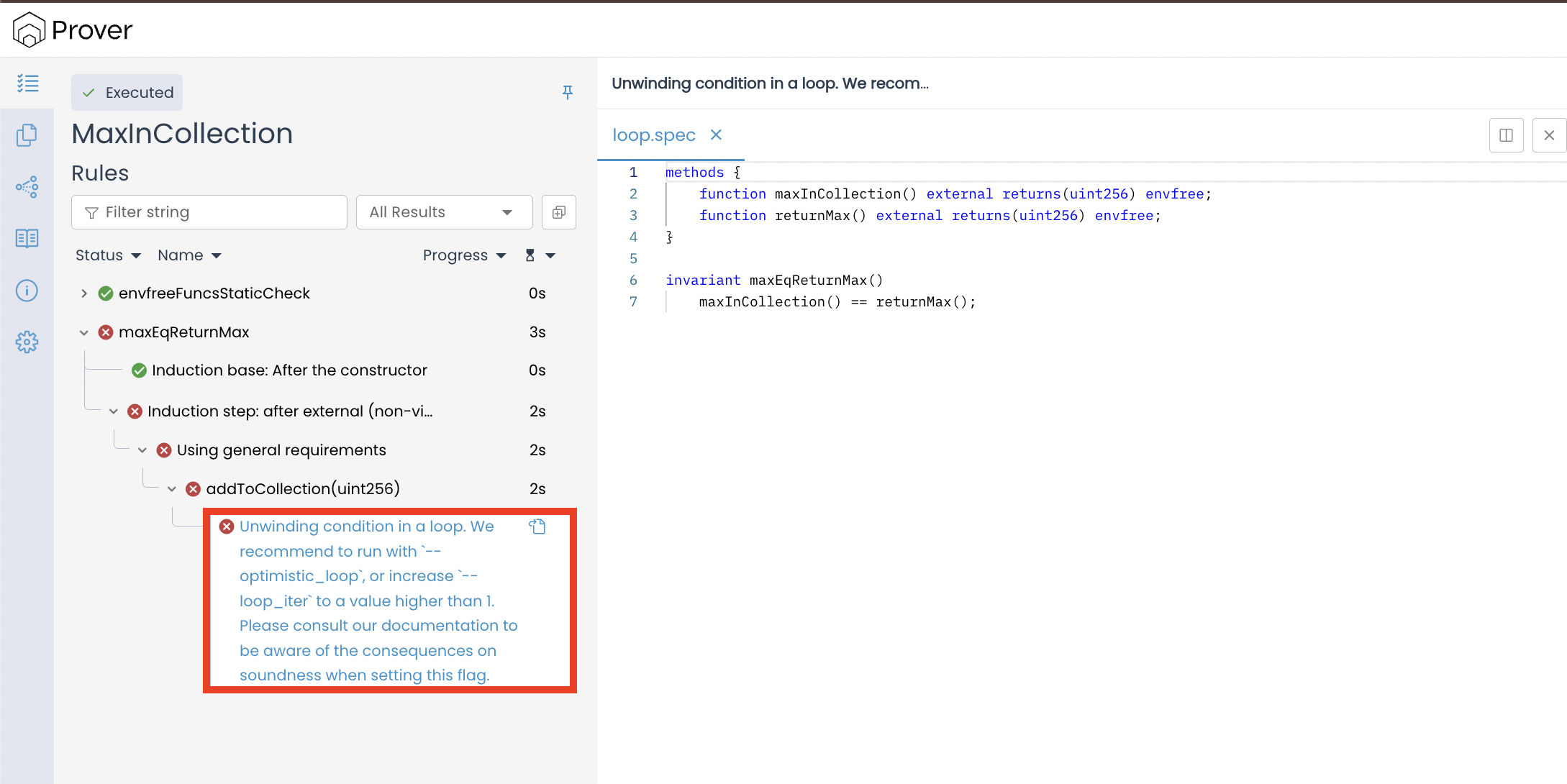

As mentioned earlier, the Certora Prover uses bounded loop unrolling to handle this problem. The technique limits how many times a loop is explored during verification, with the default bound set to one iteration. Once this limit is reached, the Prover stops exploring further because each additional iteration doubles the number of symbolic paths it must analyze. As a result, the remaining paths are left unproven.

In formal verification, proving an invariant requires showing that it holds for every possible state transition, including all iterations of any loop. If even one potential path is left unchecked, the inductive step of the proof becomes incomplete. That’s why the Prover marks the invariant maxEqReturnMax() as failed:

It is very important to understand that any computation with an unbounded number of steps is hard for the Prover to reason about symbolically. And this difficulty isn’t limited to for/while loops in your Solidity code. The same problem appears even in places where no explicit loop is visible. Let’s examine a concrete example of such hidden loops: Solidity strings.

Solidity string: The Classic Case of Hidden Loops

To understand how strings lead to “unwinding condition in a loop” errors, consider the smart contract below that stores a string in the state variable txt and lets anyone update it via setTxt():

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Example {

string public txt;

function setTxt(string memory _txt) external {

txt = _txt;

}

}

Now, consider the following specification that tries to prove the stored string always equals the input:

methods{

function setTxt(string) external envfree;

function txt() external returns(string) envfree;

}

rule storedStringShouldEqualToInput() {

string _txt;

//call

setTxt(_txt);

//assertions

assert _txt == txt();

}

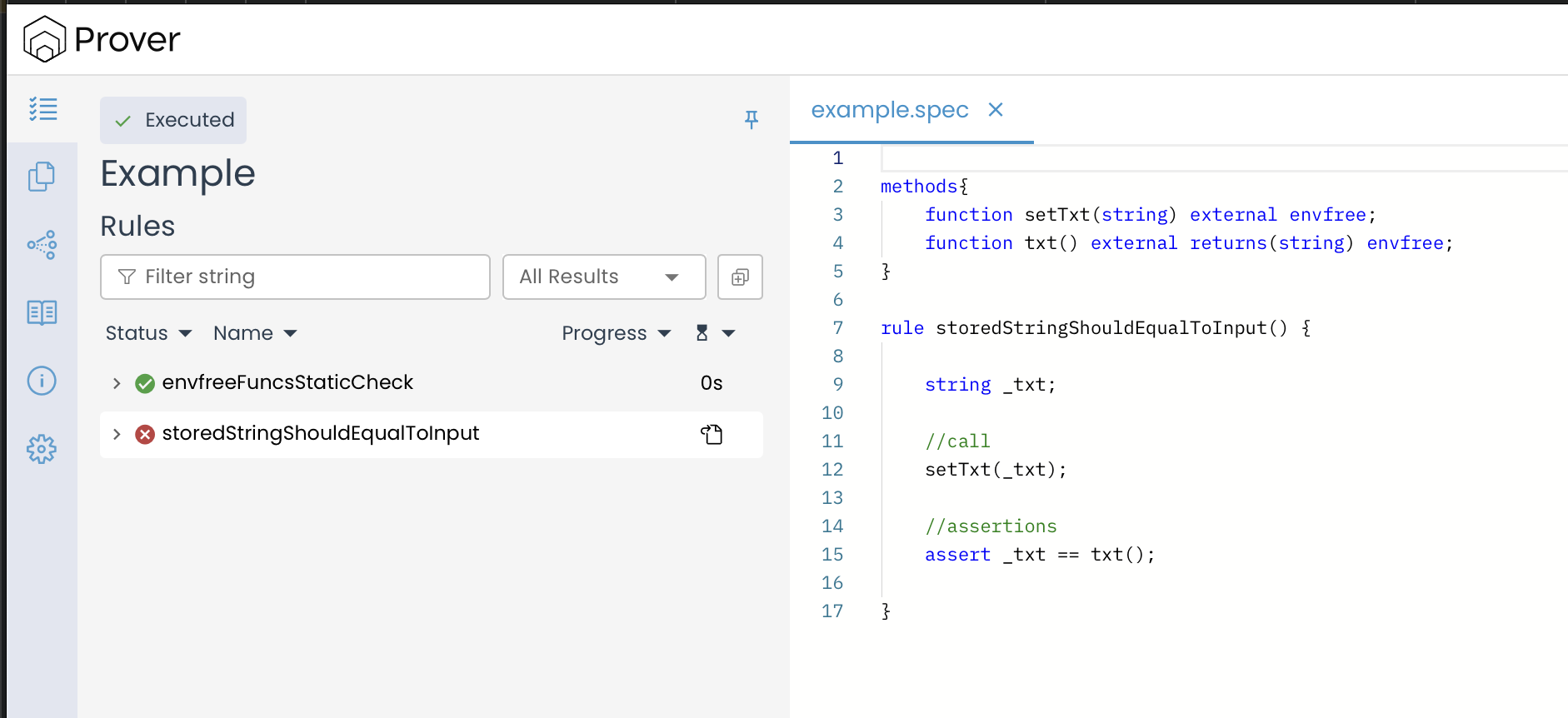

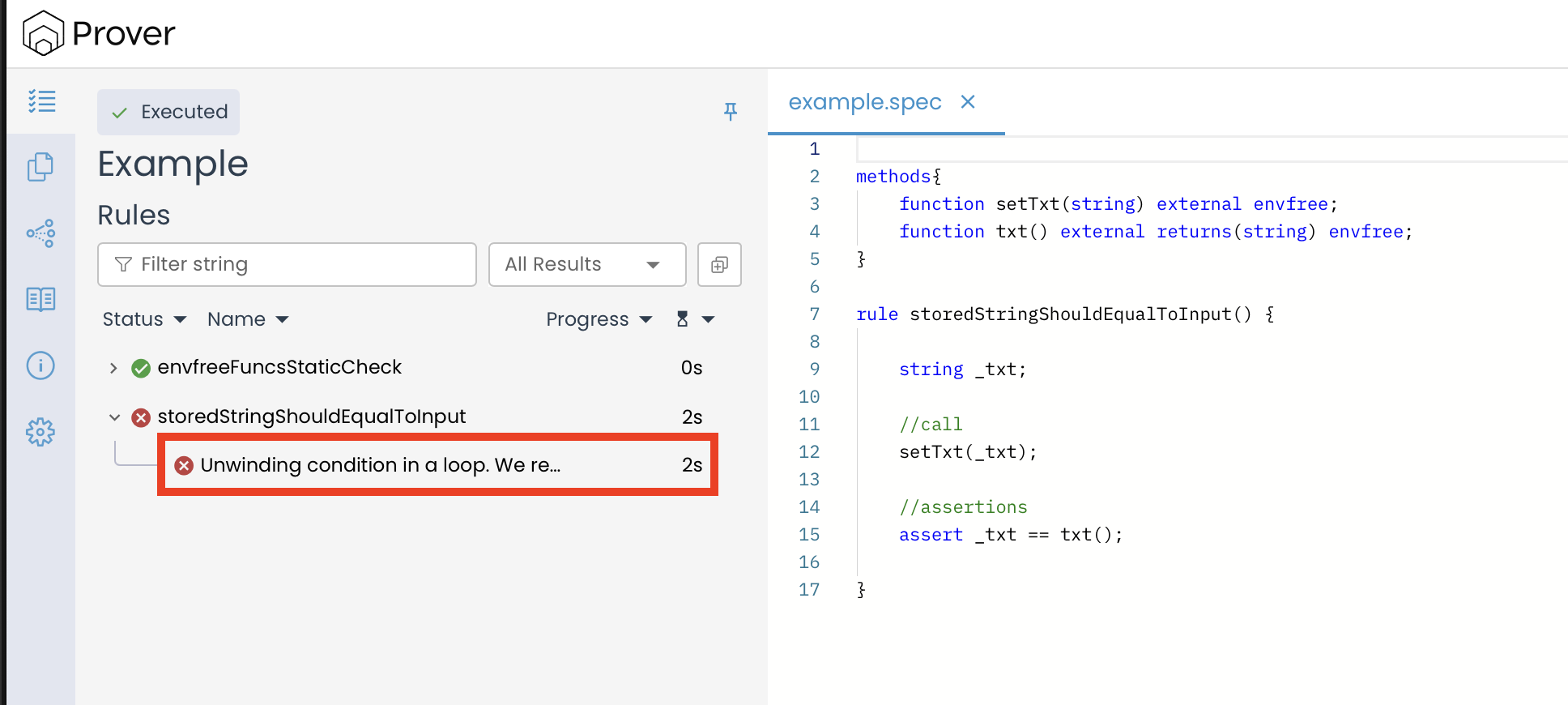

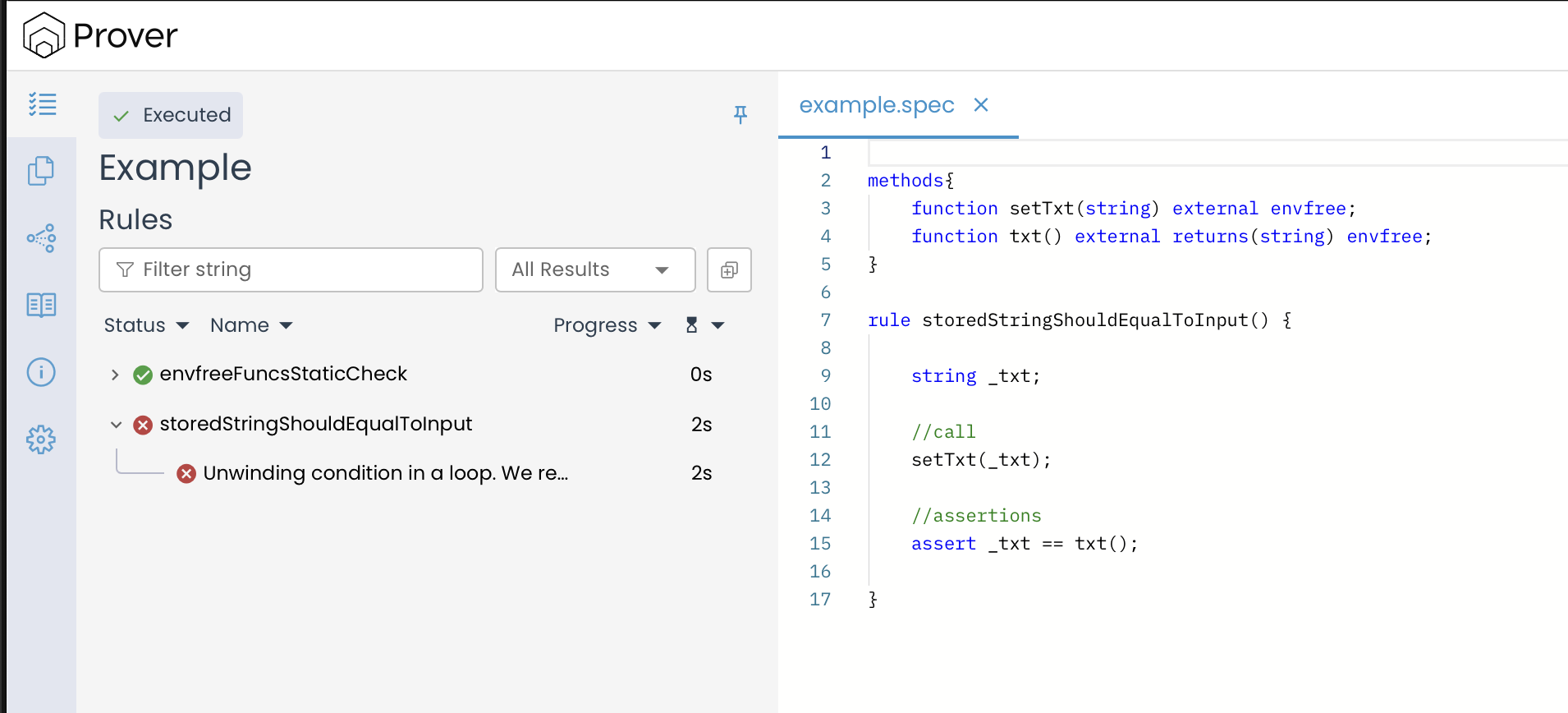

If you run the Prover with this spec, the rule fails:

And you’ll see the familiar “Unwinding condition in a loop” error, just like in the previous example involving an explicit loop.

You might be wondering why this error shows up when the code doesn’t contain any explicit loop.

The reason is simple: a hidden loop.

In Solidity, a string is not a single value but a dynamic array of bytes. However, due to the EVM’s 256-bit word architecture, when you work with dynamic arrays, the compiler and the EVM handle them by copying 32-byte chunks at a time.

This repeated, word-based copying are the hidden loop that the Prover encounters in the compiled bytecode.

In our specification, four hidden loops get triggered during string handling:

-

Copying from

calldatatomemory(The Entrance)- What happens: When you call

setTxt(_txt), the input string arrives in a temporary, read-only holding area calledcalldata. To actually use or process that string inside the function, the EVM must first move it into the function’s workspace, calledmemory. - The Loop: This transfer is done 32 bytes at a time. The EVM loops until the entire string has been moved from

calldatatomemory.

- What happens: When you call

-

Copying from

memorytostorage(The Assignment)- What happens: The assignment

txt = _txt;saves the string permanently. It moves the data from the temporarymemoryworkspace into the contract’sstorage, which is where your contract’s state lives on the blockchain. - The Loop: Since this is a permanent write, the EVM runs a loop to copy the string word-by-word (32 bytes at a time) into the contract’s designated storage slots. This is the main point of failure for verification.

- What happens: The assignment

-

Copying from

storageback tomemory(The Read)- What happens: When you call the public getter

txt(), the contract has to fetch the stored string data. It loads the string from its permanentstoragelocation back into temporarymemoryso it can be returned. - The Loop: Yet another internal loop runs, reading the string’s 32-byte words out of storage one by one.

- What happens: When you call the public getter

-

Comparing Strings (The Assertion)

- What happens: In your assertion,

assert _txt == txt();, the Prover must check if the two symbolic strings are equal. - The Loop: The only way to check equality for two dynamic arrays is to compare them word-by-word from beginning to end, which is the definition of a final hidden loop.

- What happens: In your assertion,

For concrete execution (running the code with a specific input, like the string "Hello"), this hidden loop is simple. The string’s length is a known, fixed number, so the loop runs a definite number of times. Everything is predictable.

However, for a symbolic execution engine like the Certora Prover, the input _txt isn’t a fixed string. It’s a symbolic value, meaning it represents every possible string at once—from an empty string to one of maximum size.

The Prover is now forced to reason about an unbounded family of executions. It has to check whether the property holds, no matter the string’s length or what bytes it contains. This creates two huge problems:

Problem 1: Unknown Loop Size (The Unbounded Search)

The first challenge arises because the string’s length is symbolic (unknown). This means the loop counter that controls the 32-byte copying process is also symbolic.

- For a specific string, the loop runs a set number of times (e.g., exactly 3 times).

- For the Prover, the loop could run any number of times (e.g., 0, 1, 10, or 100 times).

The Prover must, therefore, check not just one execution path, but an entire family of paths, one corresponding to every possible length the string could take. While this alone creates a huge, technically unbounded search space, this issue is made exponentially worse by the second problem: branching inside the loop.

Problem 2: Exponential Branching (The Doubling Effect)

The total number of paths explodes because the hidden loop frequently hits conditional checks (like comparing the current 32-byte word). Since the Prover doesn’t know the symbolic string’s contents, it can’t determine the outcome of the check.

To guarantee correctness, the Prover must explore both possibilities simultaneously. This forces the execution path to split, requiring the Prover to explore the consequences of the condition being true and the condition being false. This exploration effectively doubles the number of execution paths with every single iteration of the loop.

For Example:

- If the hidden loop runs just 3 times, and there’s one conditional check in each iteration, the Prover must analyze

2 x 2 x 2 = 8separate paths. - If the symbolic string is long enough to trigger 10 loop iterations, the Prover has to analyze

2^10 = 1,024paths.

This combination of unbounded length and exponential branching is what creates the path explosion problem, quickly rendering the verification process computationally impossible.

The Prover gets overwhelmed by the enormous and rapidly growing number of possible execution paths and is forced to stop exploring the loop after a fixed number of iterations using bounded loop unrolling.

Because the Prover cannot check all possible paths (i.e., it cannot fully unroll the loop for all symbolic lengths), the proof is considered incomplete. Therefore, it cannot prove that the property holds for all possible strings, which is why the rule storedStringShouldEqualToInput() fails to verify successfully.

Revisiting the “Cause”

We can see that the Prover failed to verify both rules: maxEqReturnMax() and storedStringShouldEqualToInput(), not because the properties are false, but because the Prover cannot finish reasoning about them.

- In the case of

maxEqReturnMax(), the loop insidereturnMax()can, in principle, run up to2²⁵⁶−1times — once for every possible element in the array. If we denote the array length asn, the Prover must attempt to unroll the loop for every possible value ofn, which is computationally infeasible. - In the case of

storedStringShouldEqualToInput(), the hidden loop insidetxt = _txtcan run once for every 32 bytes in the string. Since the input length is symbolic, the Prover must consider all possible string lengths, which again leads to unbounded exploration.

In both cases, the root cause is the same: the Prover cannot symbolically explore an unbounded number of loop iterations.

This leaves us with a question: what options do we have for handling these cases?

The “Solution”: Configuration Flags

The Certora Prover provides two configuration options to help deal with loops. While these do not provide complete proofs of correctness, they are useful tools for controlling the Prover’s behavior.

1. Increasing the Unrolling Bound with loop_iter

The first and most straightforward option is to tell the Prover to unroll the loop more times using the --loop_iter flag. This can be done either from the terminal or through the configuration file.

From the terminal:

certoraRun confs/<your-config-file>.conf --loop_iter <N>

Or inside a configuration file:

{

"files": [

"contracts/<YourContract>.sol:<ContractName>"

],

"verify": "<ContractName>:specs/<your-spec-file>.spec",

"loop_iter": "<N>"

}

In the terminal command and configuration file examples above, <N> specifies the maximum number of loop iterations the Prover will explore before stopping**.**

Using the loop_iter Flag in Our Rule

To understand how the --loop_iter flag works in practice, let’s apply this to our string example and run the Prover with the following command:

certoraRun confs/example.conf --loop_iter 3

When we run the prover with the above command, here is what is going to happen in practice:

- The Prover will now unroll up to 3 iterations of the hidden loop (the byte-copying loop inside

txt = _txt). - Since each iteration copies one 32-byte word, this means the Prover can successfully verify the property for strings up to 96 bytes (3 × 32 = 96) in length.

- However, for strings longer than 96 bytes, the Prover reaches its unrolling bound. At that point, those paths remain unproven.

- As a result, the rule

storedStringShouldEqualToInput()will still fail in the general case as the Prover cannot prove correctness for all string lengths.

The result will be the same no matter how much you raise the bound: any finite --loop_iter only proves the property for strings up to that number of 32-byte words. Larger strings remain unproven, and increasing the bound rapidly slows the Prover.

2. Skipping Beyond the Bound with optimistic_loop

The second option takes a very different approach. Instead of increasing the bound, the Prover can be told to assume everything beyond the bound works fine. That’s what --optimistic_loop does.

From the terminal:

certoraRun confs/<your-config-file>.conf --optimistic_loop

Or inside a configuration file:

{

"files": [

"contracts/<YourContract>.sol:<ContractName>"

],

"verify": "<ContractName>:specs/<your-spec-file>.spec",

"optimistic_loop": true

}

Normally, when the Prover hits its loop bound and sees that the loop could continue, it marks that path as unproven.

With --optimistic_loop, the Prover changes strategy:

- For iterations within the bound, it behaves normally and checks every case.

- For iterations beyond the bound, it assumes that the property will continue to hold without actually exploring those paths.

Using the optimistic_loop Flag in Our Rule

To understand how the --optimistic_loop flag works in practice, let’s apply this to our string example and run the Prover with following command:

certoraRun confs/example.conf --optimistic_loop

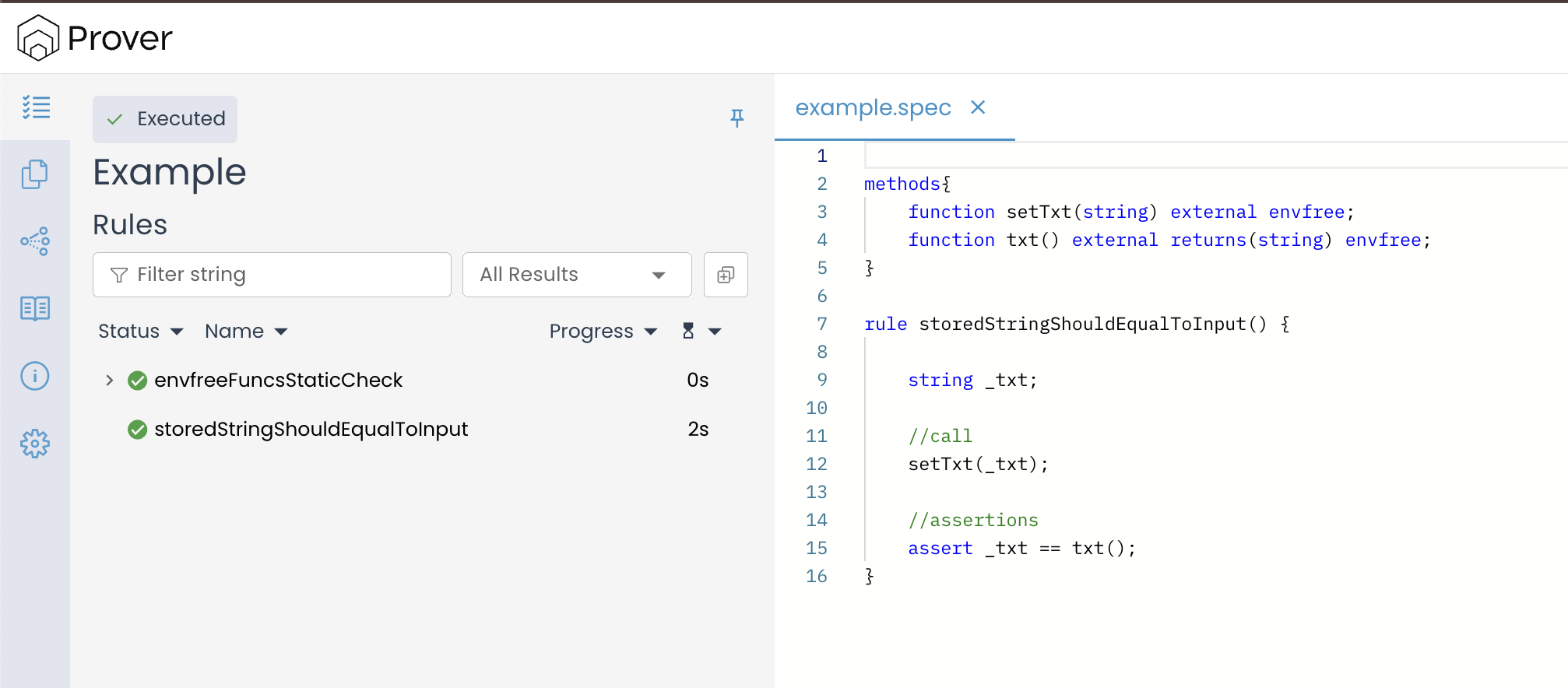

When we run the prover with the above command, this is what is going to happen in practice:

- The Prover still explores the loop for a small number of iterations (its default unrolling bound).

- Once it hits that bound, instead of reporting an “unwinding condition in a loop” error, it assumes the property continues to hold for all remaining cases.

- As a result, the rule

storedStringShouldEqualToInput()now passes verification, even though longer string lengths were never fully checked.

This approach is called “optimistic” because the Prover essentially hopes that what it saw in the first few iterations will keep holding true for all future ones.

We can see that with --loop_iter, the Prover explores only up to the bound (3 iterations in our example). Anything longer remains unproven, so the verification fails. However, with --optimistic_loop, the Prover takes a shortcut: it assumes that if the property holds within the explored bound, it also holds beyond it. This removes the unwinding failure and makes the rule pass.

While these flags are useful for debugging and managing verification, neither provides a complete, sound proof for an unknown and unbounded loops.

--loop_iteris incomplete.--optimistic_loopis unsound (it makes assumptions).

Wrapping Up

In this chapter, we saw why loops, both explicit and hidden, pose such a major challenge in formal verification. In both situations, the Prover cannot symbolically explore an unknown and unbounded number of iterations. To make progress, it relies on two configuration flags: --loop_iter and --optimistic_loop

The --loop_iter flag increases the number of iterations explored, but this only proves correctness for small inputs and therefore remains incomplete. The --optimistic_loop flag allows the Prover to skip beyond the bound by assuming correctness, but that assumption may be wrong, making it unsound.

These workarounds are helpful for debugging, quick checks, or catching shallow bugs. However, they cannot provide a complete proof when dealing with unbounded loops.