Introduction

In the previous chapter, we learned about parametric rules, which allow us to formally verify properties that are expected to hold regardless of which function is called. This is particularly useful for verifying universal invariants. But what if the desired behavior isn’t universal, and instead depends on the specific function being called? For instance, consider the scenarios:

- The

ownerof any contract should stay the same, except when the owner callschangeOwnerorrenounceOwnership. - The total supply of an ERC-20 token should stay the same, except when tokens are being minted or burned.

How do we handle such cases where a property generally holds but has known exceptions based on the function? Or what if you simply want to exclude certain administrative methods from general invariant checks altogether?

In this chapter, we learn how to use method properties to enforce function-specific assertions in parametric rules. We’ll also see how to exclude certain functions from verification when those rules aren’t applicable.

What Are Method Properties?

The code below shows a parametric rule — one that applies to all functions.

rule someParametricRule() {

env e;

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e, args);

assert property_1;

}

Whether you need to enforce function-specific assertions or exclude certain functions from the rule, you need a way to distinguish one function from another. This is where method properties come in.

In CVL, method properties are attributes accessible on the method variable (like f) using field-like syntax (e.g., f.propertyName). These properties provide information about the function that f refers to at runtime, allowing your rule logic to adapt based on the specific method being invoked.

The available method properties include:

f.selector: This returns the 4-byte function selector (a hash of the function signature, e.g.,0xa9059cbb) that can be used to identify specific named functions (e.g.,f.selector == sig:transfer(address,uint256).selector) to apply function-specific assertions in a parametric rule.f.isPure: This returnstrueif the functionfis declared with thepurekeyword in Solidity. This can be useful to exclude purely computational functions from rules that are only meaningful for state-modifying logic.f.isView: This returnstrueif the functionfis declared with theviewkeyword. This can be used to skip read-only functions when writing rules concerned with state changes. We’ll explore the benefits of this in a later section.f.isFallback: This returnstrueiffrepresents afallback()orreceive()function. This is helpful when you need to write rules governing fallback behavior—like payable requirements or special handling for low-level calls.f.numberOfArguments: This returns the number of arguments that the functionfexpects.f.contract: This returns the contract in which the function is defined. This is useful when you’re verifying multiple contracts at once, or dealing with inheritance—like when two contracts have functions with the same name and arguments. This is something we’ll explore in later chapters, as our current examples involve only a single contract.

Out of all these, the most commonly used method properties are f.selector, f.isView, and f.isPure. These cover the most typical use cases—like identifying a specific function (using the selector) or skipping read-only and computational functions (isView and isPure) when writing rules focused on state changes. To keep things practical, we’ll focus on these properties in the upcoming examples and show how they help write more precise and efficient parametric rules.

Enforcing Function-Dependent Assertion In Parametric Rule

To understand how method properties can be used to enforce function-dependent assertions within a parametric rule, consider the ERC-20 implementation RareToken shown below, which includes both mint and burn functionality:

//SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract RareToken {

uint256 public totalSupply;

address public owner;

mapping(address => uint256) public balanceOf;

mapping(address => mapping(address => uint256)) public allowance;

event Transfer(address indexed from, address indexed to, uint256 value);

event Approval(address indexed owner, address indexed spender, uint256 value);

modifier onlyOwner() {

require(msg.sender == owner, "Unauthorized");

_;

}

constructor(uint256 _initialSupply) {

owner = msg.sender;

if (_initialSupply > 0) {

_mint(msg.sender, _initialSupply);

}

}

function transfer(address to, uint256 amount) public virtual returns (bool) {

_transfer(msg.sender, to, amount);

return true;

}

function approve(address spender, uint256 amount) public virtual returns (bool) {

_approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

return true;

}

function transferFrom(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public virtual returns (bool) {

address spender = msg.sender;

uint256 currentAllowance = allowance[from][spender];

require(currentAllowance >= amount, "Allowance exceeded");

if (currentAllowance != type(uint256).max) {

_approve(from, spender, currentAllowance - amount);

}

_transfer(from, to, amount);

return true;

}

function mint(address account, uint256 amount) public onlyOwner {

_mint(account, amount);

}

function burn(uint256 amount) public virtual {

_burn(msg.sender, amount);

}

function _transfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) internal virtual {

require(from != address(0), "Invalid sender");

require(to != address(0), "Invalid recipient");

uint256 fromBalance = balanceOf[from];

require(fromBalance >= amount, "Insufficient balance");

balanceOf[from] = fromBalance - amount;

balanceOf[to] += amount;

emit Transfer(from, to, amount);

}

function _mint(address account, uint256 amount) internal virtual {

require(account != address(0), "Invalid recipient");

totalSupply += amount;

balanceOf[account] += amount;

emit Transfer(address(0), account, amount);

}

function _burn(address account, uint256 amount) internal virtual {

require(account != address(0), "Invalid burner");

uint256 accountBalance = balanceOf[account];

require(accountBalance >= amount, "Burn exceeds balance");

balanceOf[account] = accountBalance - amount;

totalSupply -= amount;

emit Transfer(account, address(0), amount);

}

function _approve(address ownerAccount, address spender, uint256 amount) internal virtual {

require(ownerAccount != address(0), "Invalid owner");

require(spender != address(0), "Invalid spender");

allowance[ownerAccount][spender] = amount;

emit Approval(ownerAccount, spender, amount);

}

}

Since the above ERC-20 implementation includes mint() and burn(), the totalSupply value is expected to change during those function calls—unlike the ERC-20 implementation we used in the last chapter, where no function was allowed to alter the supply.

Now, suppose we want to write a parametric rule for the RareToken contract that enforces the following behavior:

- When the

mint()function is called, thetotalSupplymust not decrease (it can either increase or stay the same if the amount is zero). - When the

burn()function is called, thetotalSupplymust not increase (it can either decrease or stay the same if the amount is zero). - For any other function (like

transfer,approve,transferFrom), thetotalSupplymust remain unchanged.

To define a parametric rule that enforces the above behaviour, the rule must ensures the following:

- The rule should first record the initial value of the

totalSupplyvariable before any function execution to establish a reference point for state comparison. - To evaluate the impact of multiple functions on the

totalSupplystate, the rule should employ a parametric framework that executes each target function one at a time. - After each function completes execution, the rule must record the updated value of

totalSupplyto track state modifications. - Finally, the rule should enforces three critical assertions based on the executed function.

The following rule, totalSupplyIntegrityCheck, implements all these steps. It captures the totalSupply before and after each function execution, invokes any method using a parametric setup, and then enforces the expected behavior depending on which function was called:

rule totalSupplyIntegrityCheck() {

env e;

// Step 1: Record initial state

mathint supplyBefore = totalSupply(e);

// Step 2: Execute an arbitrary function

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e, args);

// Step 3: Record updated state

mathint supplyAfter = totalSupply(e);

// Step 4: Function-specific assertions

if (f.selector == sig:mint(address,uint256).selector) {

assert supplyAfter >= supplyBefore, "Total supply should not decrease after mint()";

}

else if (f.selector == sig:burn(uint256).selector) {

assert supplyAfter <= supplyBefore, "Total supply should not increase after burn()";

}

else {

assert supplyAfter == supplyBefore, "Total supply must remain unchanged for other function calls";

}

}

In the above rule, we accessed the function selector of an arbitrary function (f) using f.selector, and we derived the function selector of a known function using the sig:functionName(...).selector notation. We then used it to compare whether the executed function f corresponds to a specific named function like mint() or burn() to enforce function-specific assertions within our parametric rule.

The above rule simply enforces the following behaviour:

- If the

mint()function is executed (identified byf.selector == sig:mint(address,uint256).selector), thetotalSupplyvalue must not decrease compared to its initial value. - If the

burn()function is executed (identified byf.selector == sig:burn(uint256).selector), thetotalSupplyvalue must not increase compared to its initial value. - For all other function calls, the rule enforces that the

totalSupplyvalue must remain unchanged, ensuring that no unintended function modifies thetotalSupplyvariable.

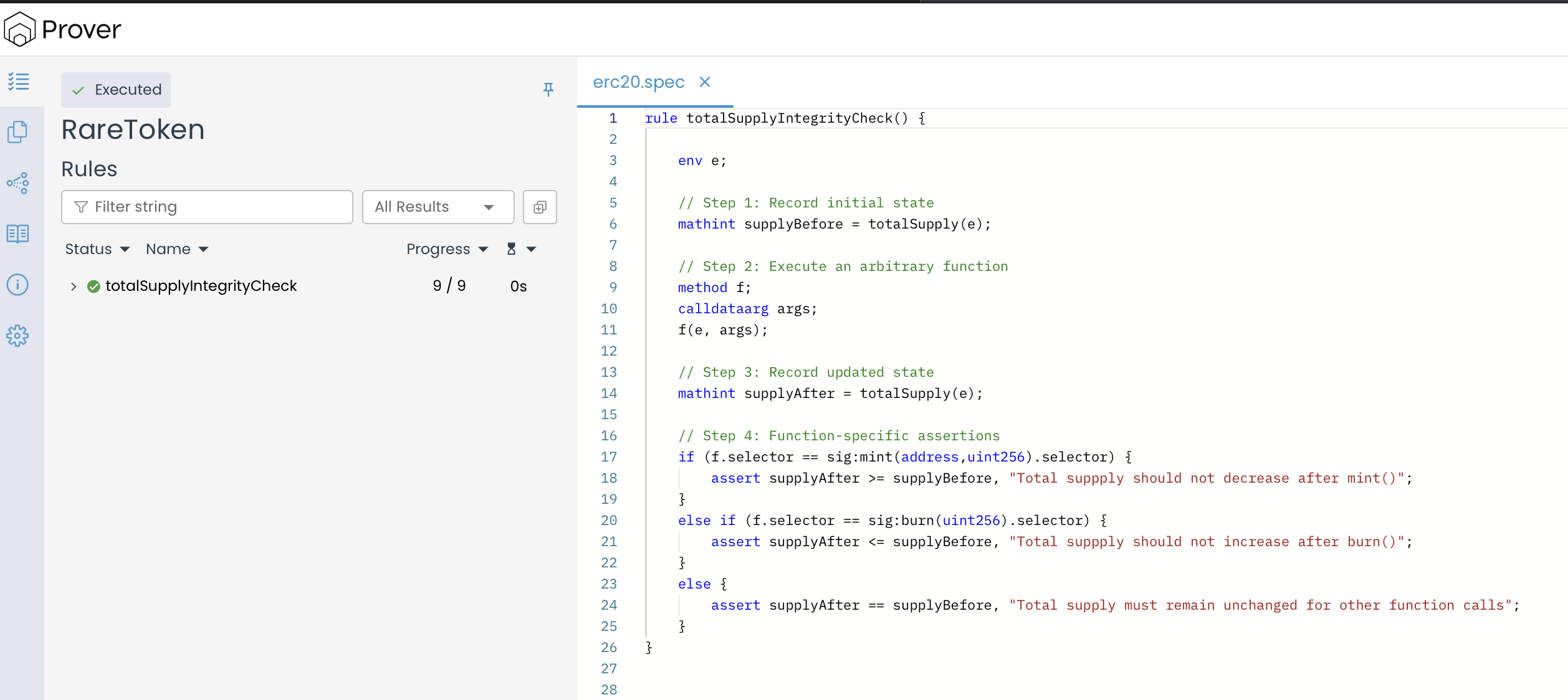

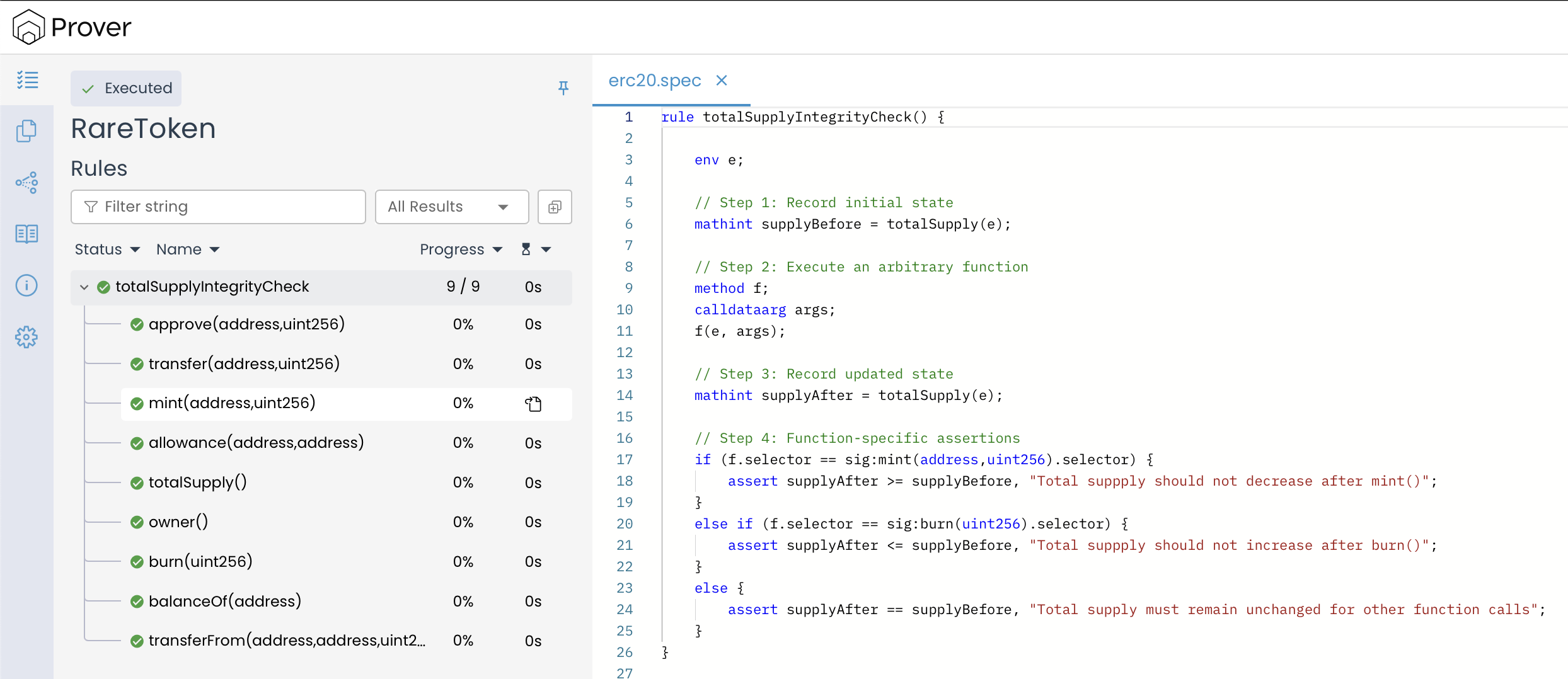

To view the results of our parametric rule, set up the Certora Prover environment by placing the RareToken contract and its specification in the appropriate directory. Then, run the verification process. If the contract meets the rule’s conditions, the prover will confirm a successful verification with no detected violations, as shown in the results below.

The verification results confirm that the totalSupplyIntegrityCheck rule was successfully executed, with all nine checks passing without any detected violations. This validates that the behavior of the mint(), burn(), and other functions in the RareToken contract is consistent with the rule’s expectations—totalSupply increases after mint(), decreases after burn(), and remains unchanged for all other functions.

The above rule successfully uses conditional logic based on f.selector to apply the correct assertions after executing each function f. This ensures every function compatible with the rule’s parameters is checked against the appropriate expectation based on its identity.

Optimizing Parametric Rule with filtered Blocks

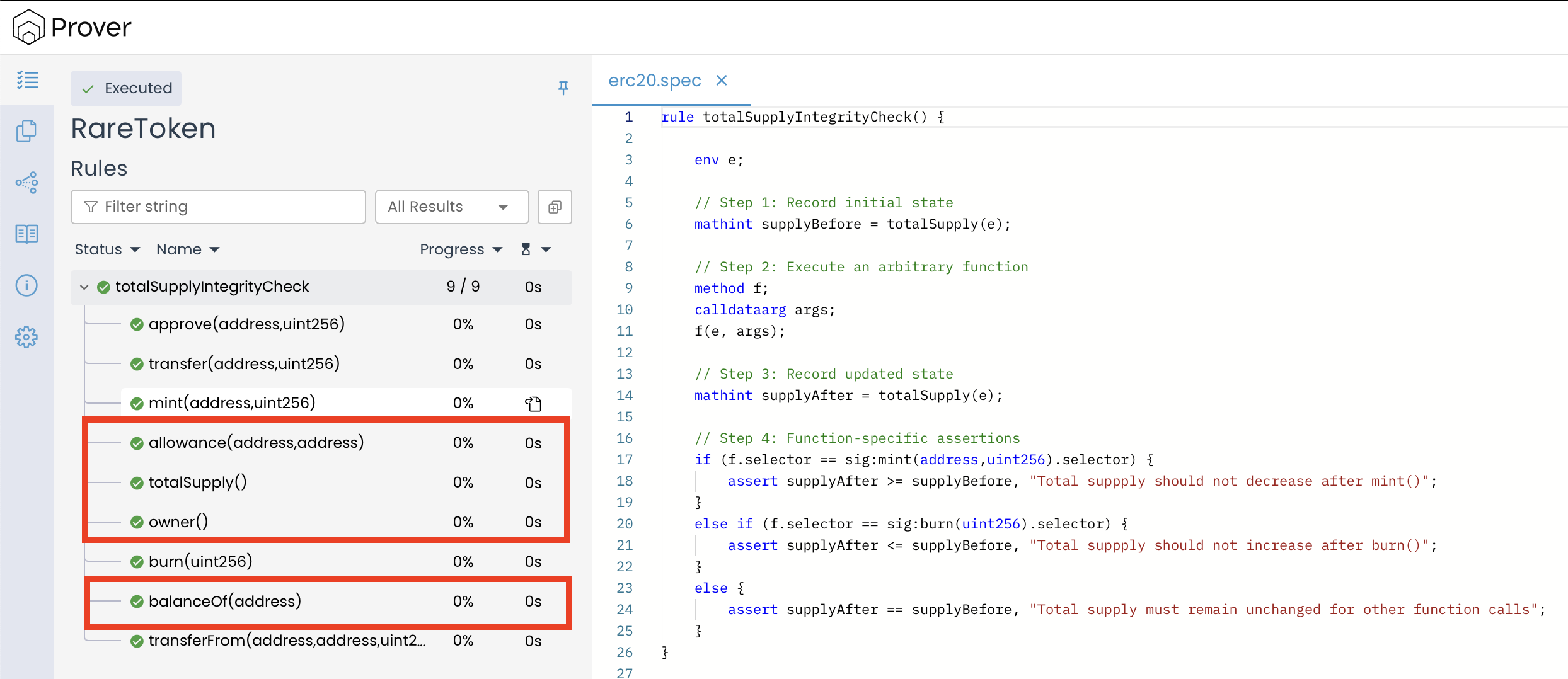

When we review the verification report, we notice that the Certora Prover has applied our assertion checks to every function in the contract—including read-only ones like totalSupply(), balanceOf(), and owner(). These functions are marked as view in Solidity, which means they only read from the blockchain state and do not modify anything. Because of this, running state-change rules on these functions doesn’t make much sense and doesn’t help us catch meaningful bugs.

Even though verifying them isn’t technically wrong, it causes extra computational work and slows down the process. That’s why it’s important to exclude functions that don’t impact the contract state when they aren’t relevant to the rule being tested. This is where the filtered block comes in handy.

The filter block allows us to selectively include or exclude methods from being analyzed by a parametric rule based on method properties like isView, isPure etc.

Using filtered Block to Exclude View Functions

To understand the functioning of the filter block, consider the specification below that includes a rule that contains a filter block.

rule totalSupplyIntegrityCheck(env e, method f, calldataarg args) filtered {

f -> !f.isView

} {

// Step 1: Record initial state

mathint supplyBefore = totalSupply(e);

// Step 2: Execute an arbitrary function

f(e, args);

// Step 3: Record updated state

mathint supplyAfter = totalSupply(e);

// Step 4: Function-specific assertions

if (f.selector == sig:mint(address,uint256).selector) {

assert supplyAfter >= supplyBefore, "Total supply should not decrease after mint()";

}

else if (f.selector == sig:burn(uint256).selector) {

assert supplyAfter <= supplyBefore, "Total supply should not increase after burn()";

}

else {

assert supplyAfter == supplyBefore, "Total supply must remain unchanged for other function calls";

}

}

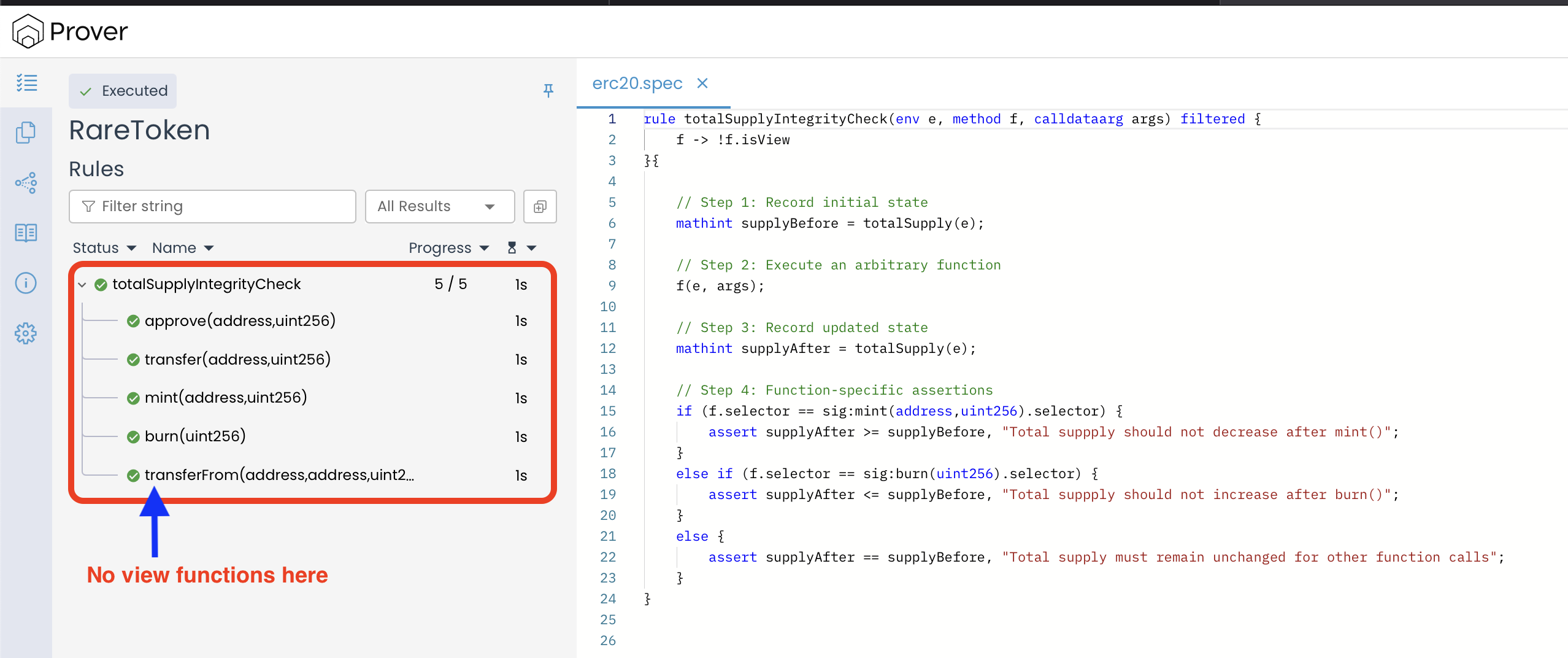

In the above rule, the line f -> !f.isView inside the filter block filtered {} acts as a filter that tells the Prover: “Only run this rule on functions where f.isView is false.” In other words, it excludes all functions marked as view from verification.

If we re-run the Prover with the above specification, we can see that view functions like totalSupply(), balanceOf(), and owner() are no longer included in the verification of this rule, as shown in the image below:

Using a filter block inside a parametric rule helps us achieve two things:

- It reduces computational overhead by skipping irrelevant functions that are guaranteed not to change the contract’s state.

- It simplifies the verification output, allowing us to focus only on the results of state-changing functions.

Wrapping Up

This is how we can utilize method properties to enforce function-specific assertions as well as exclude irrelevant functions from verification using filtered blocks.