Until now, in previous chapters, we have written rules to verify the behavior of specific methods and their impact on a contract’s state. For example:

- In Chapter 2, we wrote a rule to verify that calling

increment()increases the value of count by one. - In Chapter 3, we wrote a rule to check that sequential calls to

increment()anddecrement()should result in an unchangedcountvalue.

But what if we want to reason about properties that should hold true regardless of which function is called? For example, consider the following properties:

- In a simple voting contract, the total number of votes should always equal the sum of votes in favor and votes against.

- In an ERC-20 contract, a user’s balance must never exceed the token’s total supply.

In this chapter, we’ll learn how to write what are known as parametric rules—rules that allow us to formally verify properties that are expected to hold regardless of which function is called.

Introduction to Parametric Rules

In CVL, a standard rule often checks state transitions after a specific function call. You typically define what state transitions are allowed using a pattern like:

rule any_general_rule{

require <setup conditions>;

mySpecificFunction(arg1, arg2);

assert <expected outcome>;

}

A parametric rule works similarly but generalizes this concept. Instead of focusing on one function(args), a parametric rule verifies a property holds true after any function is called with any valid arguments.

How CVL Handles "Any Function, Any Args”

To express this idea of “any function with any valid arguments,” CVL provides two special types:

method: Represents any public or external function within the contract you are verifying. Declaring a variable of typemethodmeans that the rule can dynamically reference and execute any function in the contract.calldataarg: Represents the arguments for a function call. Since different functions need different inputs,calldataargensures that valid arguments are automatically provided for whichever function (method) is being tested.

The Parametric Call Syntax

These two special types allow us to create what we call a parametric call, which enables a rule to access and call every public or external method of the contract under verification, using the following syntax:

rule someParametricRule() {

env e;

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e,args)

//Any assert statement should go here

assert <property_1>;

assert <property_2>;

}

The line f(e, args) is called a parametric call. It allows us to test all public or external functions in the contract instead of picking one manually. Here’s how it works:

frepresents any function in the contract. Instead of specifying a particular function, this variable ensures that every function gets tested one by one.argsrepresents a set of valid input values. Since different functions have different parameters, args ensures that the correct type and number of inputs are provided for each function.e: Provides the necessary environmental context (like sender address, block number) for the function call simulation.

Essentially, the line f(e, args); tells the Certora Prover: “For every function f in this contract, execute it with valid arguments args in a simulated environment e.”

By placing assert statements after the f(e, args); line, we define properties that must hold true universally, after any function call completes. This makes parametric rules ideal for verifying core invariants and general safety properties of smart contracts.

Identifying Invariants In ERC-20

Let’s apply what we’ve learned to formally verify an invariant of an ERC-20 Implementation shown below:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract RareToken {

uint8 public immutable decimals = 18;

uint256 public immutable totalSupply;

mapping(address => uint256) private balances;

mapping(address => mapping(address => uint256)) private allowances;

event Transfer(address indexed from, address indexed to, uint256 value);

event Approval(address indexed owner, address indexed spender, uint256 value);

constructor(uint256 _initialSupply) {

require(_initialSupply > 0, "Invalid initial supply");

totalSupply = _initialSupply * 10 ** uint256(decimals);

balances[msg.sender] = totalSupply;

emit Transfer(address(0), msg.sender, totalSupply);

}

function balanceOf(address account) public view returns (uint256) {

return balances[account];

}

function transfer(address recipient, uint256 amount) public returns (bool) {

require(recipient != address(0), "ERC20: transfer to zero address");

require(balances[msg.sender] >= amount, "Insufficient balance");

balances[msg.sender] -= amount;

balances[recipient] += amount;

emit Transfer(msg.sender, recipient, amount);

return true;

}

function approve(address spender, uint256 amount) public returns (bool) {

require(spender != address(0), "ERC20: approve to zero address");

allowances[msg.sender][spender] = amount;

emit Approval(msg.sender, spender, amount);

return true;

}

function allowance(address owner_, address spender) public view returns (uint256) {

return allowances[owner_][spender];

}

function transferFrom(

address sender,

address recipient,

uint256 amount

) public returns (bool) {

require(recipient != address(0), "ERC20: transfer to zero address");

require(balances[sender] >= amount, "Insufficient balance");

uint256 currentAllowance = allowances[sender][msg.sender];

require(currentAllowance >= amount, "ERC20: insufficient allowance");

if (currentAllowance != type(uint256).max) {

allowances[sender][msg.sender] = currentAllowance - amount;

}

balances[sender] -= amount;

balances[recipient] += amount;

emit Transfer(sender, recipient, amount);

return true;

}

}

As we’ve learned, the purpose of writing parametric rules is to verify smart contract properties that should always hold true across different function calls. In the case of our RareToken contract, one key invariant is: Total Supply Stability.

Since the contract does not include mint or burn functionality, the total supply is initialized once at deployment and must remain constant throughout the contract’s lifetime. In other words, no function should ever modify the value returned by totalSupply().

Let’s see how we can write a parametric rule to verify total supply integrity.

Formally Verifying Total Supply Consistency

Once we’ve identified the key invariants of the contract that we want to verify, follow these steps to write a parametric rule:

1. Define the Rule

Use the rule keyword, followed by a descriptive name for the rule:

rule totalSupplyIsConstant() { }

2. Declare the Execution Environment

Define an env variable to represent the function’s execution environment:

rule totalSupplyIsConstant() {

env e;

}

3. Capture the Pre-Call State

Since we need to compare the value of totalSupply before and after function execution, we store its initial state:

rule totalSupplyIsConstant() {

env e;

mathint beforeSupply = totalSupply(e);

}

4. Model the Function Execution

Declare a method variable to represent any function call and define arguments that might be passed:

rule totalSupplyIsConstant() {

env e;

mathint beforeSupply = totalSupply(e);

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e, args); // Execute the function call with the given arguments

}

5. Capture the Post-Call State

After executing the function, we will store the updated value of totalSupply:

rule totalSupplyIsConstant() {

env e;

mathint beforeSupply = totalSupply(e);

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e, args);

mathint afterSupply = totalSupply(e);

}

6. Enforce the Total Supply Consistency

In the case of our RareToken contract, we want to ensure that the totalSupply variable should never change after any function execution. We use the assert statement (assert beforeSupply == afterSupply) to explicitly enforce this condition:

rule totalSupplyIsConstant() {

env e;

mathint beforeSupply = totalSupply(e);

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e, args);

mathint afterSupply = totalSupply(e);

assert beforeSupply == afterSupply;

}

Running the Verification

To view the results of our parametric rule, apply what you learned in the earlier chapters: place the RareToken contract and the corresponding specification into the Certora Prover environment.

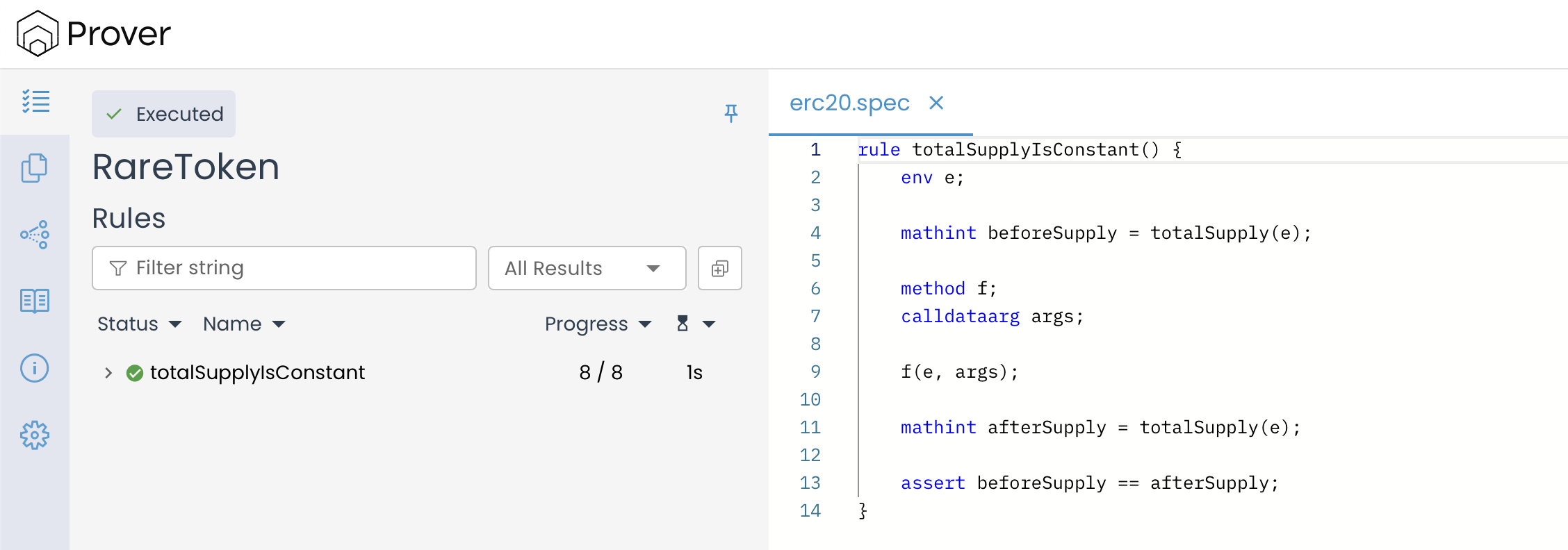

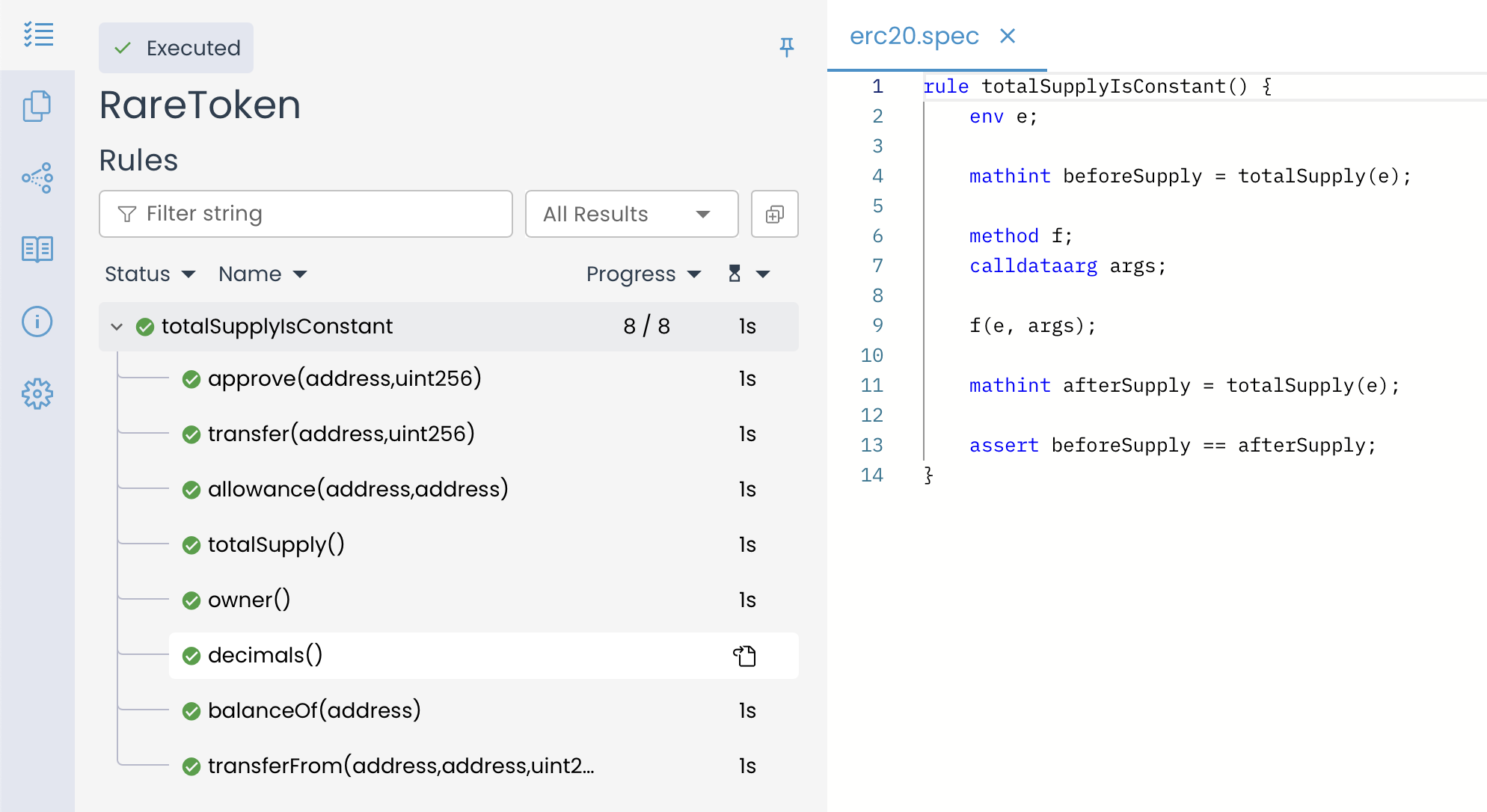

Once the setup is complete, initiate the verification process. If the contract satisfies all conditions defined by the rule, the Certora Prover will confirm a successful verification run with no detected violations, as shown in the image below:

The verification results confirm that all functions in the RareToken contract were tested against the totalSupplyIsConstant() rule. The green checkmarks(✅) next to each function indicate that the rule holds for every possible execution, ensuring that the totalSupply variable remains unchanged under any function call.

Understanding the Scope of Parametric Rule

One important thing to understand about a parametric rule is that it is designed to analyze the effect of just one function call at a time. That means the Prover is not checking what happens after a series of calls—it’s only concerned with a single call to one function and what the contract state looks like immediately after that.

Here’s what happens when the Prover evaluates a parametric rule:

- It begins from an initial contract state—this is the state before any function has been called.

- It selects one function from the contract and checks whether—under the given preconditions—there exists any valid input that could lead to a violation of the rule’s assertions.

- This process is repeated for each function in the contract.

- The rule passes verification (✅) only if none of the functions, under any valid inputs, cause an assertion to fail.

To understand the evaluation process of a parametric rule more clearly, consider the Counter contract. It includes two external functions: increment(), which increases the count, and transferOwnership(), which updates the owner address. The ownership-related functionality is included simply to introduce additional functions, so we can observe how a parametric rule behaves when applied across a variety of function types.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Counter {

uint256 public count;

address public owner;

// Define custom errors

error Unauthorized();

error InvalidAddress();

// Emit events for important state changes

event OwnershipTransferred(address indexed previousOwner, address indexed newOwner);

event CountUpdated(uint256 newCount);

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

emit OwnershipTransferred(address(0), msg.sender);

}

modifier onlyOwner() {

if (msg.sender != owner) revert Unauthorized();

_;

}

function increment() external {

count += 1;

emit CountUpdated(count);

}

function transferOwnership(address _newOwner) external onlyOwner {

if (_newOwner == address(0)) revert InvalidAddress();

emit OwnershipTransferred(owner, _newOwner);

owner = _newOwner;

}

}

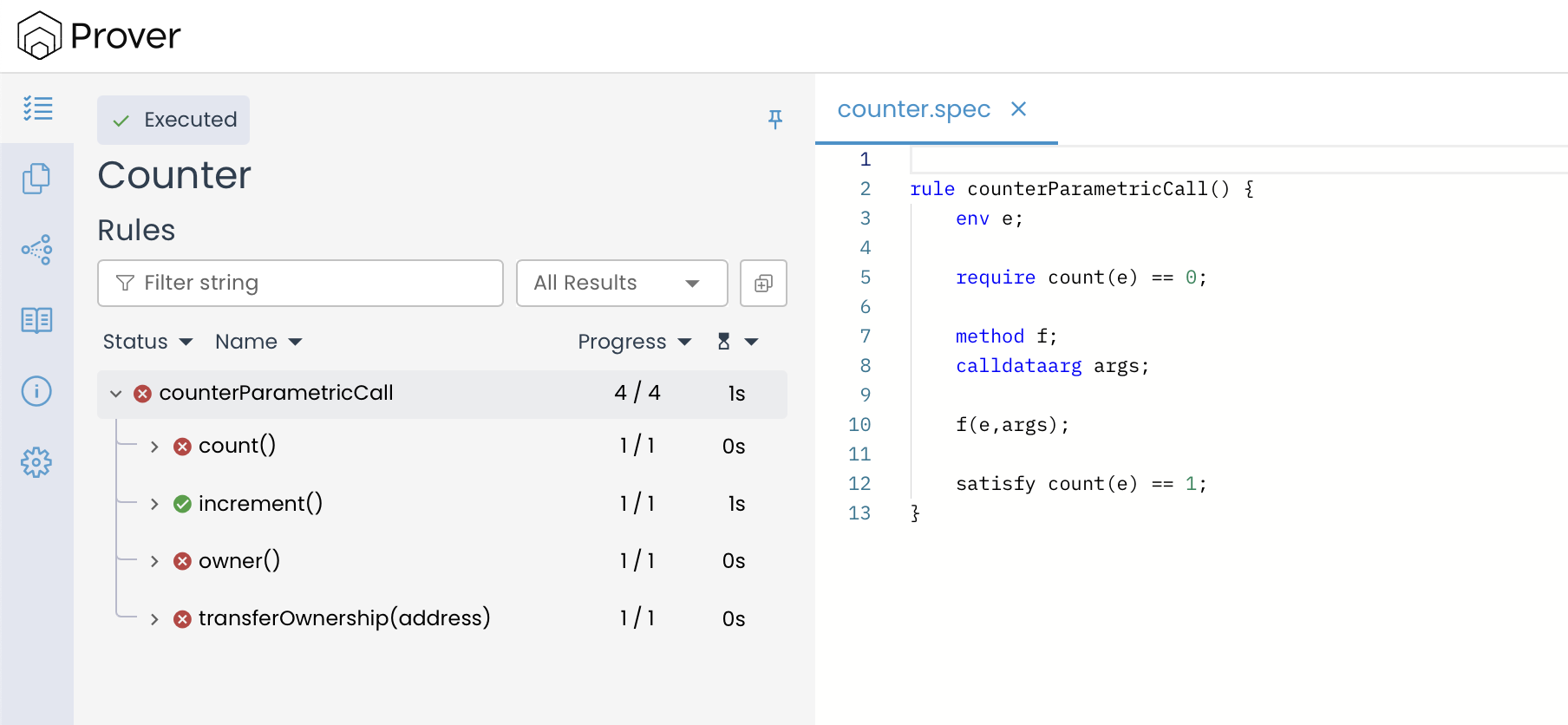

Now consider the specification below that defines a parametric rule called counterParametricCall().

rule counterParametricCall() {

env e;

require count(e) == 0;

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e,args);

satisfy count(e) == 2 ;

}

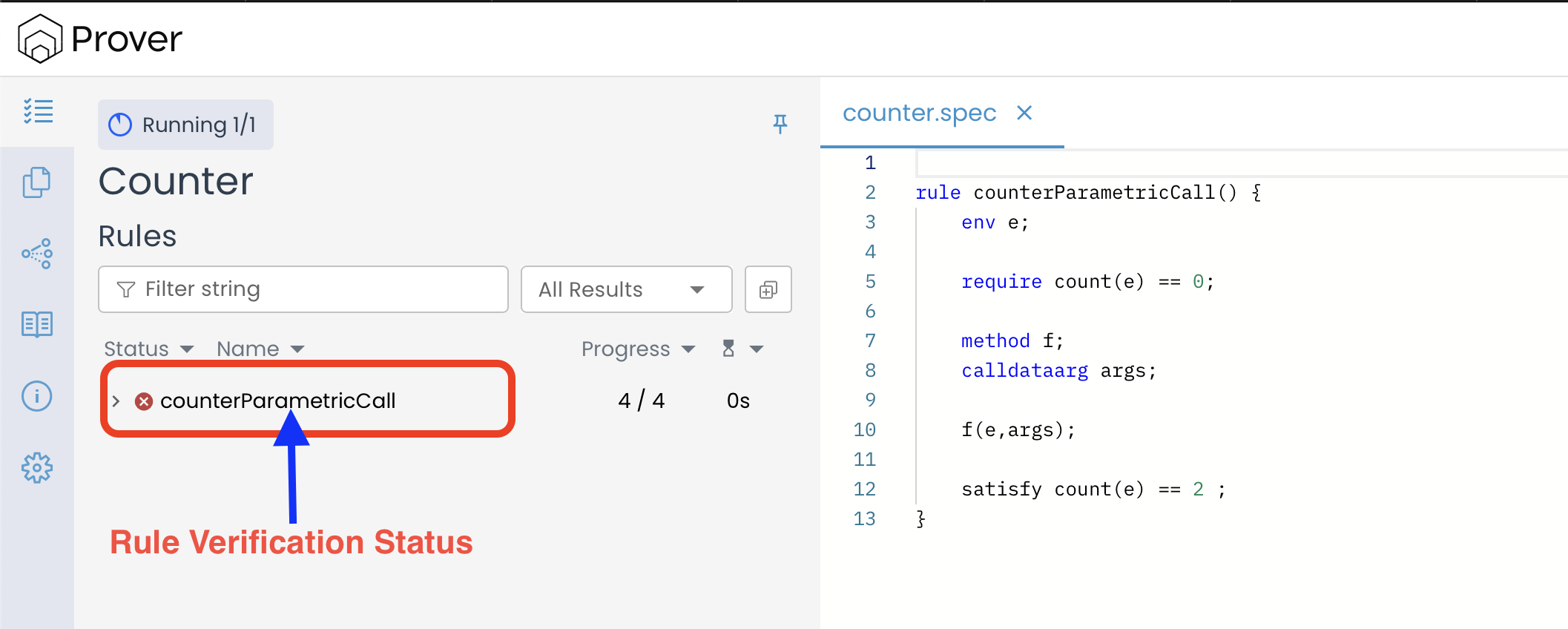

Since our rule counterParametricCall() includes the satisfy statement satisfy count(e) == 2;, we are asking the Prover whether there is at least one possible way to reach a state where count is 2, starting from an initial state where count is 0.

But there’s more to it—the rule also includes a parametric function call (f(e, args)) between the require and satisfy statements. This shifts the question from a general reachability check to a more focused query:

“Does there exist any single function f in the contract such that, when executed once with some valid arguments args__, it transitions the state directly from count == 0 to count == 2?”

In the case of our Counter contract, the only function available is increment(), which increases the counter by 1 per call. Since no function can increase the counter by 2 in a single execution, the Prover cannot find any function that satisfies the condition count(e) == 2.

Therefore, the rule will fail verification, which is the expected and correct outcome—as illustrated below:

It’s very crucial to note that a parametric rule only analyzes the effect of one external function call in isolation. It does not examine sequences of calls or complex interactions within a single transaction. For example, while the above rule proves no single call can make count == 2, it is possible to reach count == 2 within one transaction if another smart contract were to call the increment() function twice in sequence. That scenario involves multiple function calls initiated within a single transaction, which is outside the scope of this chapter.

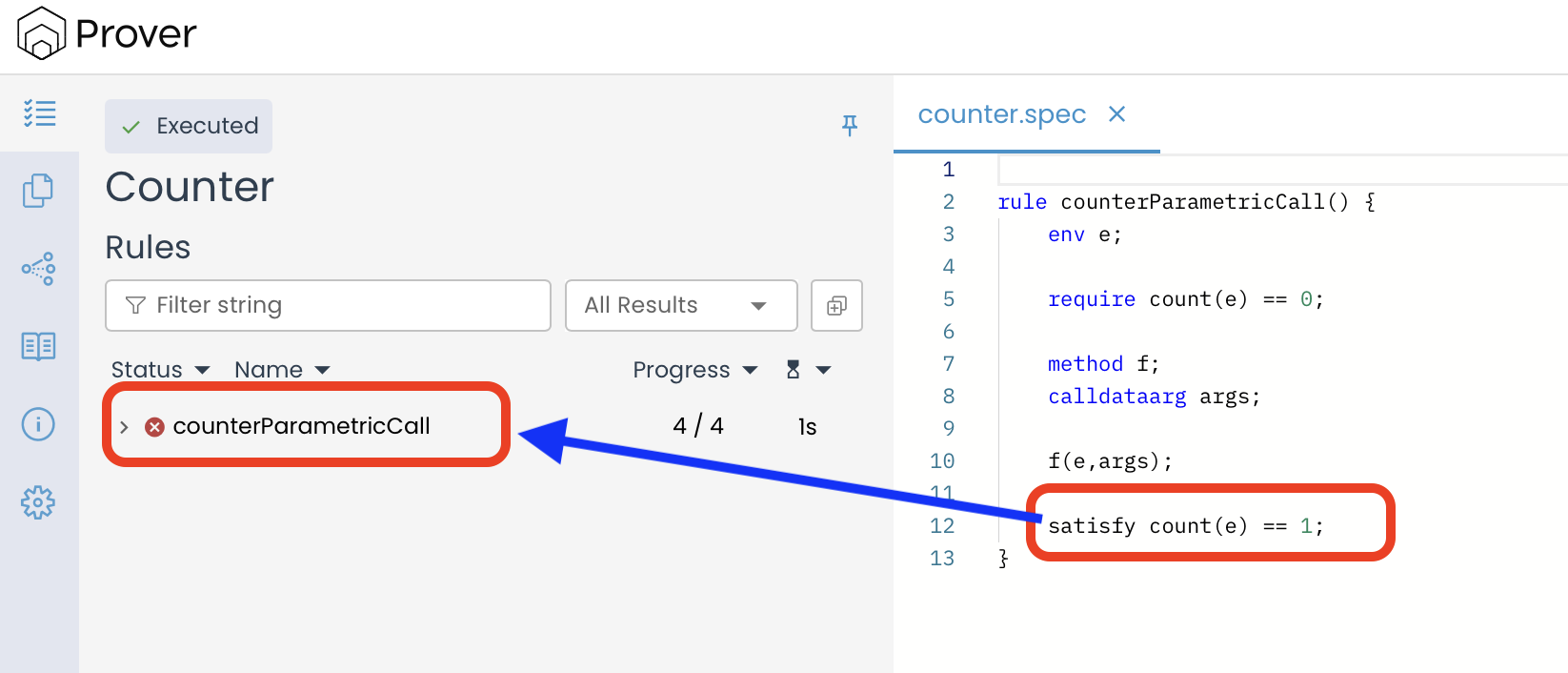

However, even if we relaxed the rule to check satisfy count(e) == 1 instead of satisfy count(e) == 2, the rule would still not pass, as shown below:

This happened because, under the hood, when evaluating a parametric rule, the Prover creates an instance of the rule for each function in the contract. It tests each of these rule instances individually against the assertions. The rule passes the verification if and only if every function instance satisfies all the conditions specified by the assert and satisfy statements. If even one function fails to meet the criteria, the entire rule fails.

In the Counter contract, only the increment() function modifies the count variable, making it the only candidate that can potentially satisfy the satisfy condition (e.g., count == 1). In contrast, transferOwnership() and the getter functions count() and owner() do not affect count at all. When the Prover evaluates the rule for these functions, it finds that none of them can produce the required state change. As a result, their rule instances fail, and since all instances must pass for the rule to succeed, the entire rule fails verification.

Wrapping Up

This is how we can use a parametric rule to verify smart contract properties that are expected to hold true across all function executions. However, there are cases where we may want to exclude certain functions from the rule or handle them differently. In the next chapter, we’ll learn how to fine-tune parametric rules to selectively enforce constraints based on specific function calls.