In the previous chapter, we learned that a specification is a piece of code written in CVL that describes the expected behavior of a smart contract. A specification mainly consists of:

- Rules

- The Methods Block

The bodies of these rules and the Methods Block are composed of CVL statements.

In this chapter, we will learn about CVL statements.

Introduction to CVL Statements

According to Certora’s official documentation, “Statements describe the steps that are simulated by the Prover when evaluating a rule.” In other words, statements define the conditions and actions that guide how the Certora Prover tests a smart contract against a rule.

CVL offers a wide range of statements for writing rules, but for now, we will focus on the following:

require– Used to specify a condition that must hold before running the rule.assert– Used to specify a condition that must hold in all execution paths for a rule to be evaluated as verified.satisfy– Used for asserting at least one valid execution path exists.

What Does “Execution Path” Mean?

When verifying a smart contract, the Prover explores different possible states and transitions to check that the rule holds under all scenarios. An execution path refers to a specific sequence of function calls and state changes that the contract goes through during verification.

Understanding the Use of assert

The assert statement in CVL is used to verify a condition that must be true during the execution of the contract. Every rule must conclude with either an assert or a satisfy statement.

If a rule does not end with either an assert or a satisfy statement, the Prover cannot determine what condition should be checked, leading to an error. For example, consider running the specification below from the previous chapter with the assert statements commented out:

methods {

function count() external returns(uint256) envfree;

function increment() external envfree;

function decrement() external envfree;

}

rule checkIncrementCall() {

//Precall Requirement

require count() == 0;

// Call OR Action

increment();

// Post-call Expectation

//assert count() == 1;

}

rule checkCounter() {

//Retrieval of Pre-call value

uint256 precallCountValue = count();

// Call

increment();

decrement();

//Retrieval of Post-call value

uint256 postcallCountValue = count();

//Post-call Expectation

//assert postcallCountValue == precallCountValue;

}

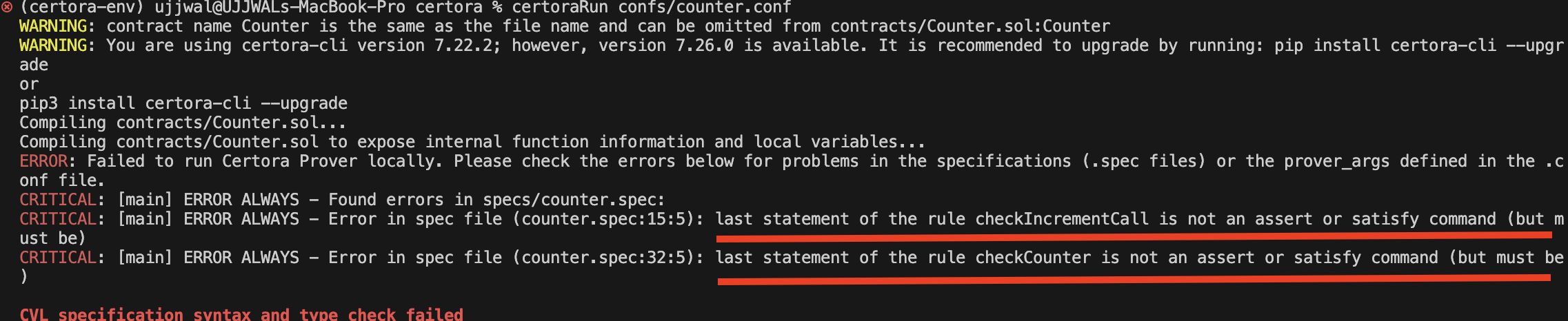

Since neither of the above rules includes an assert statement at the end, the Prover cannot determine which property to verify. This results in the error “last statement of the rule …… is not an assert or satisfy command (but must be),” as shown below.

The assert statement contains the expected state of the contract in the form of an expression, along with an optional message string describing the expression, as shown below:

assert Expression, "An Optional Message String";

//OR

assert Expression;

During verification, a rule passes if all execution paths satisfy the conditions expressed in its assert statements. However, if any assert statement evaluates to false in any execution path, the rule is considered violated.

Defining Validation Benchmarks for the Counter Contract

To better understand how the assert statement works, let’s revisit our earlier Counter example and explore its functionality in more detail.

//SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.24;

contract Counter {

uint256 public count;

function increment() external {

count++;

}

}

The contract above can be considered to be working correctly if it satisfies the following conditions during testing:

- Once the contract is deployed, the

countvariable should initialize correctly. - When

increment()is called, the value ofcountshould increase by 1.

Transforming Expectations into Assertion Checks

Now, suppose we want to formally verify our expectations for the Counter contract. To do this, we define a rule called checkCountValidity(), which ensures that the count variable starts at zero and correctly increments with each function call.

rule checkCountValidity(.......)

Here’s how the rule works, step by step:

- Capture the Initial State: We first retrieve the current value of count using the

count()getter and store it in a variable calledPrecallCountValue. This gives us a reference point before any modifications occur.

rule checkCountValidity() {

// Grabbing the initial state of the count variable

uint256 PrecallCountValue = count();

}

- Perform the increments: We then call the

increment()function three times to increase the counter.

rule checkCountValidity() {

// Grabbing the initial state of the count variable

uint256 PrecallCountValue = count();

// Call to increment()

increment();

increment();

increment();

}

- Retrieve the updated state: After executing the

increment()calls, we fetch the new value ofcountand store it inPostcallCountValue. This allows us to compare the state before and after the function executions.

rule checkCountValidity() {

// Grabbing the initial state of the count variable

uint256 PrecallCountValue = count();

// Call to increment()

increment();

increment();

increment();

// Grabbing the state of count after the increment() calls

uint256 PostcallCountValue = count();

}

- Validate the initial state: To ensure correctness, we use an

assertstatement to verify that count was initially 0—confirming that the contract starts from a known, expected state.

rule checkCountValidity() {

// Grabbing the initial state of the count variable

uint256 PrecallCountValue = count();

// Call to increment()

increment();

increment();

increment();

// Grabbing the state of count after the increment() calls

uint256 PostcallCountValue = count();

// Assertions

assert PrecallCountValue == 0;

}

- Verify the increment behavior: Finally, we assert that

counthas increased by exactly 3, confirming that each call toincrement()successfully added 1 to the value.

rule checkCountValidity() {

// Grabbing the initial state of the count variable

uint256 PrecallCountValue = count();

// Call to increment()

increment();

increment();

increment();

// Grabbing the state of count after the increment() calls

uint256 PostcallCountValue = count();

// Assertions

assert PrecallCountValue == 0;

assert PostcallCountValue == PrecallCountValue + 3;

}

We can see how we used the assert statements to enforce our expectations about the contract’s behavior.

What’s the Expected Result?

At first glance, you might expect checkCountValidity to pass the verification because:

- Default Initialization: The

Countercontract does not explicitly initialize thecountstate variable, so Solidity automatically sets it to 0. As a result, when the rule retrieves the initial value usingcount(), it should return 0, making the assertionPrecallCountValue == 0valid for any execution path. - Increment Behavior: Each call to

increment()increases thecountvariable by 1. Since the rule callsincrement()three times, the expected final value ofcountshould bePrecallCountValue + 3. Therefore, the assertionPostcallCountValue == PrecallCountValue + 3is expected to hold true for any execution path.

Running the Verification

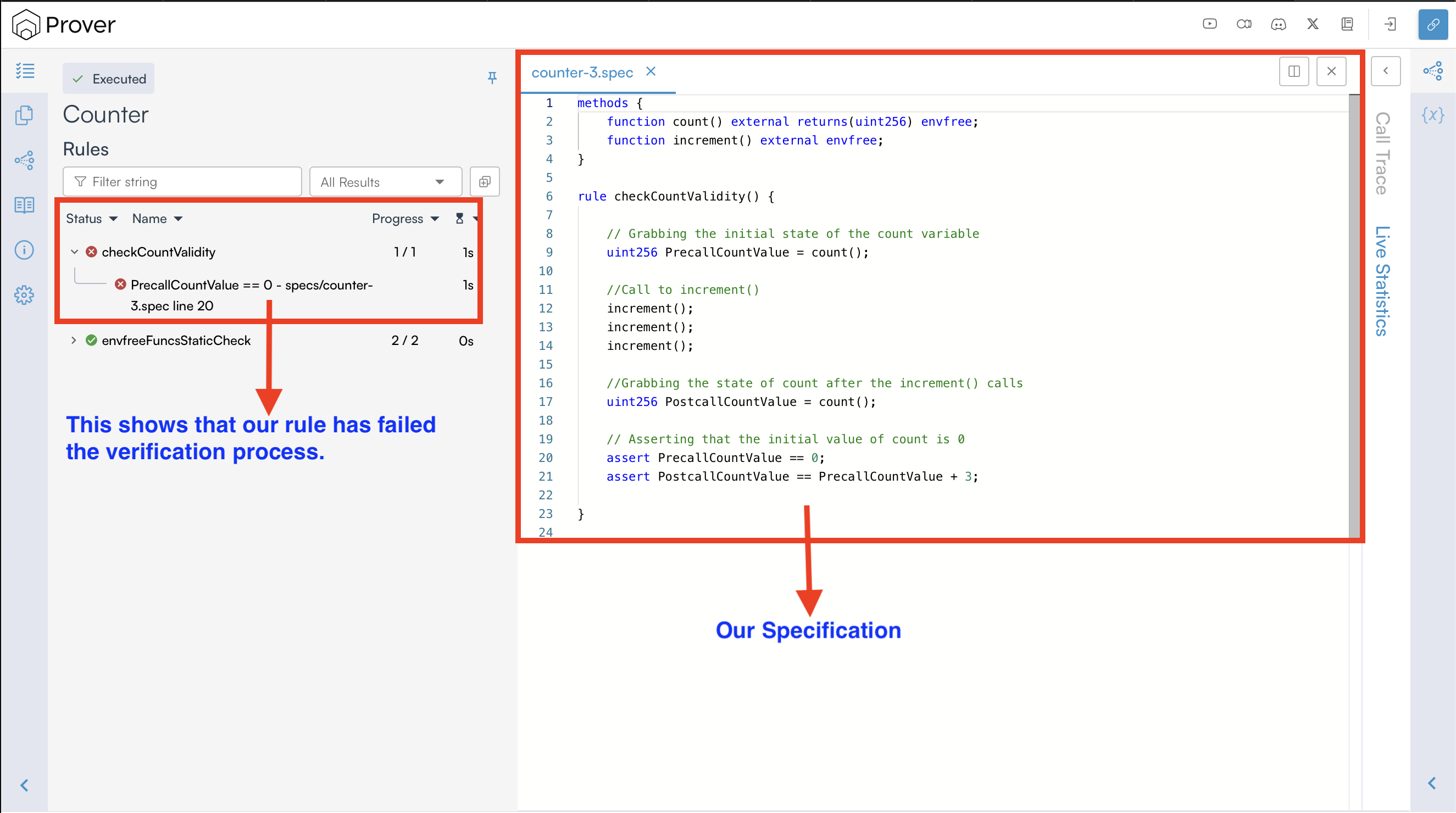

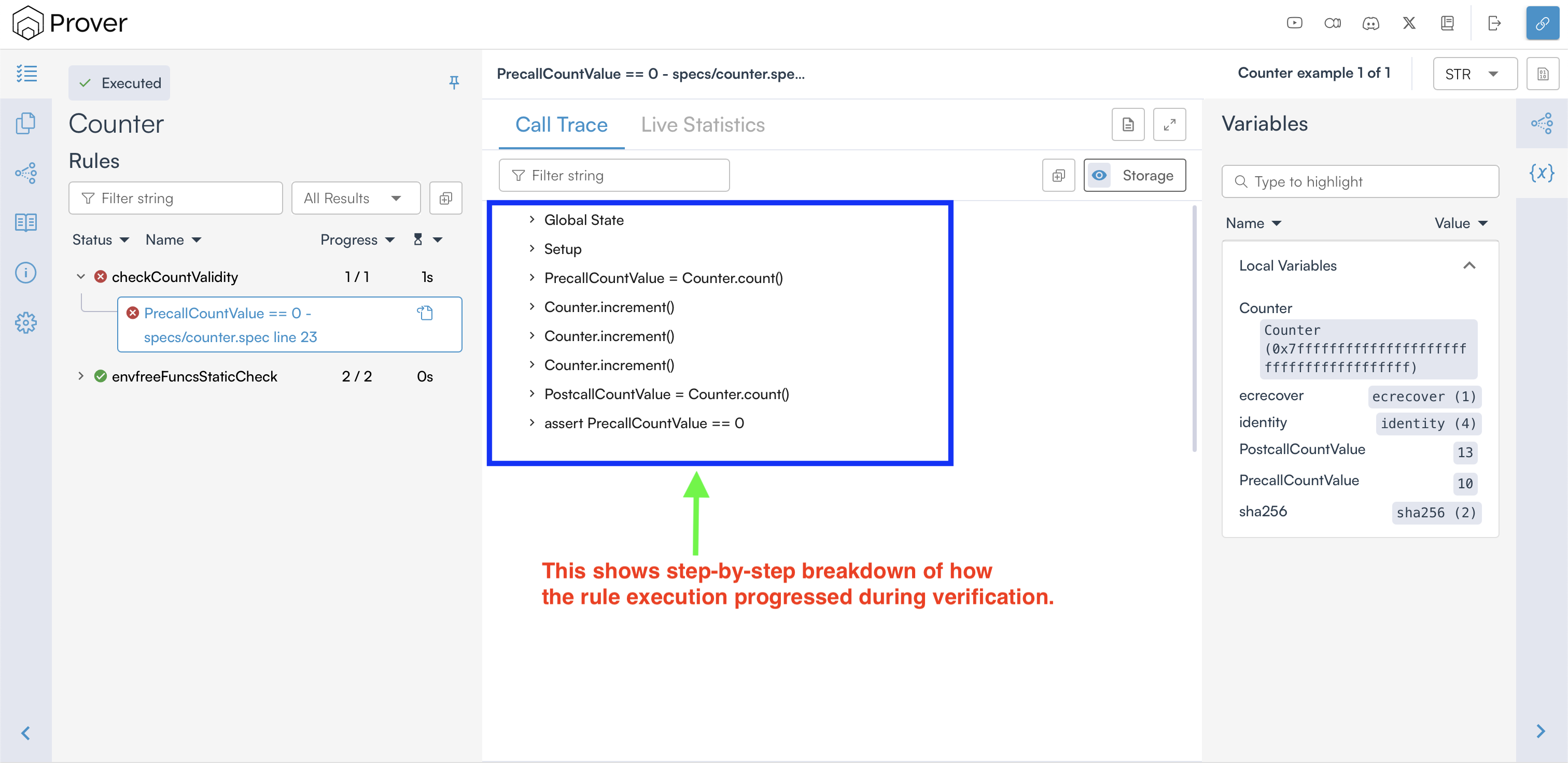

However, when you run the verification process, you will encounter an unexpected result as shown below.

In the result above, we can clearly see that the Prover failed to verify the checkCountValidity() rule. This suggests that at least one of the following conditions evaluated to false, resulting in a rule violation:

assert PrecallCountValue == 0assert PostcallCountValue == PrecallCountValue + 3

In case of a violation, the Prover generates a detailed report outlining the violation, including information about which assertion failed, the relevant variable values, and the execution steps leading to the failure.

Interpreting Verification Failures Through Counterexample

To understand the violation, the Certora Prover provides counterexamples. In simple terms, a counterexample is a specific execution path where the verification of a rule fails.

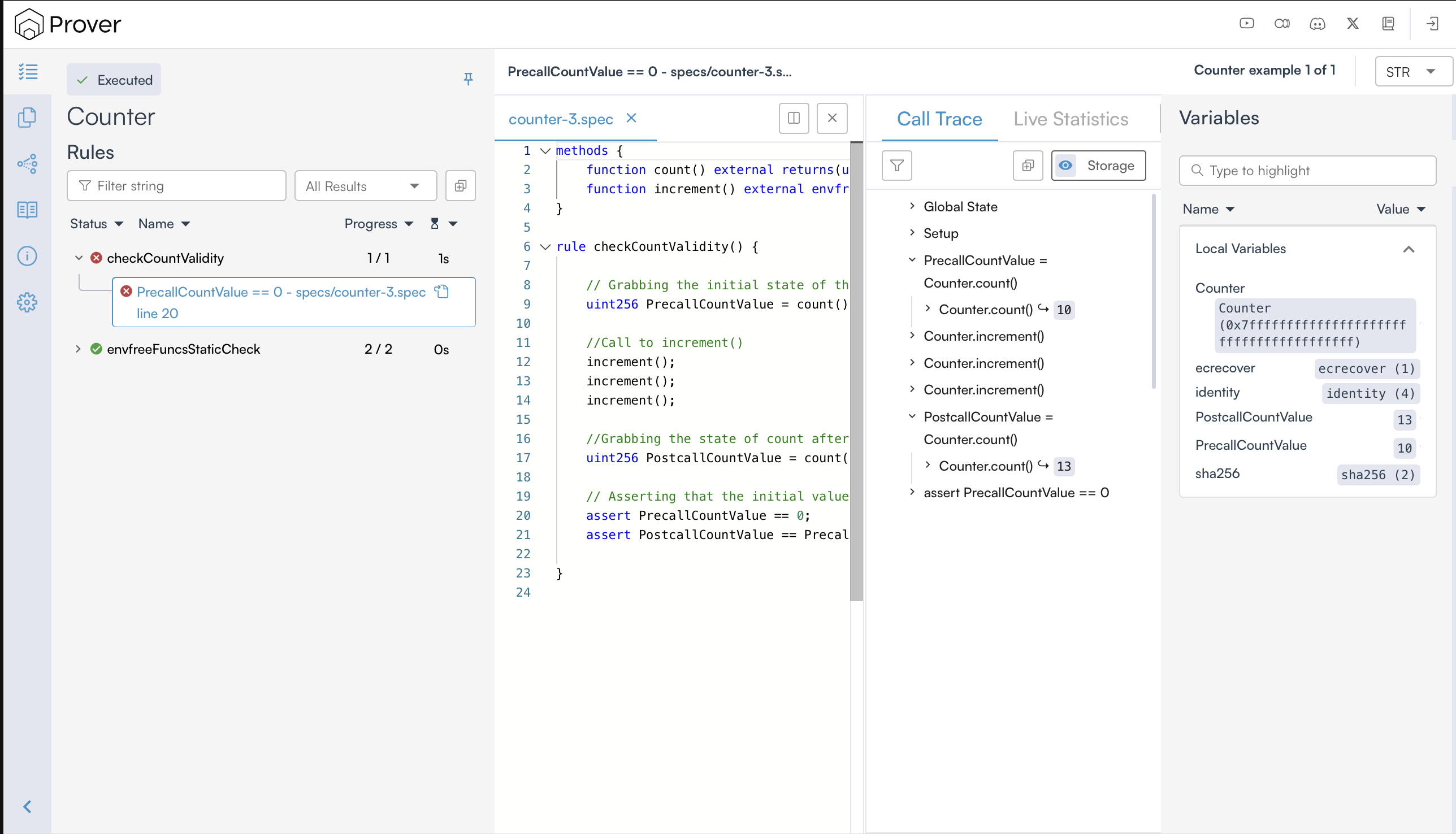

To view the counterexample of our violated rule, click the violated rule (checkCountValidity) name on the report page to get a view similar to the one below.

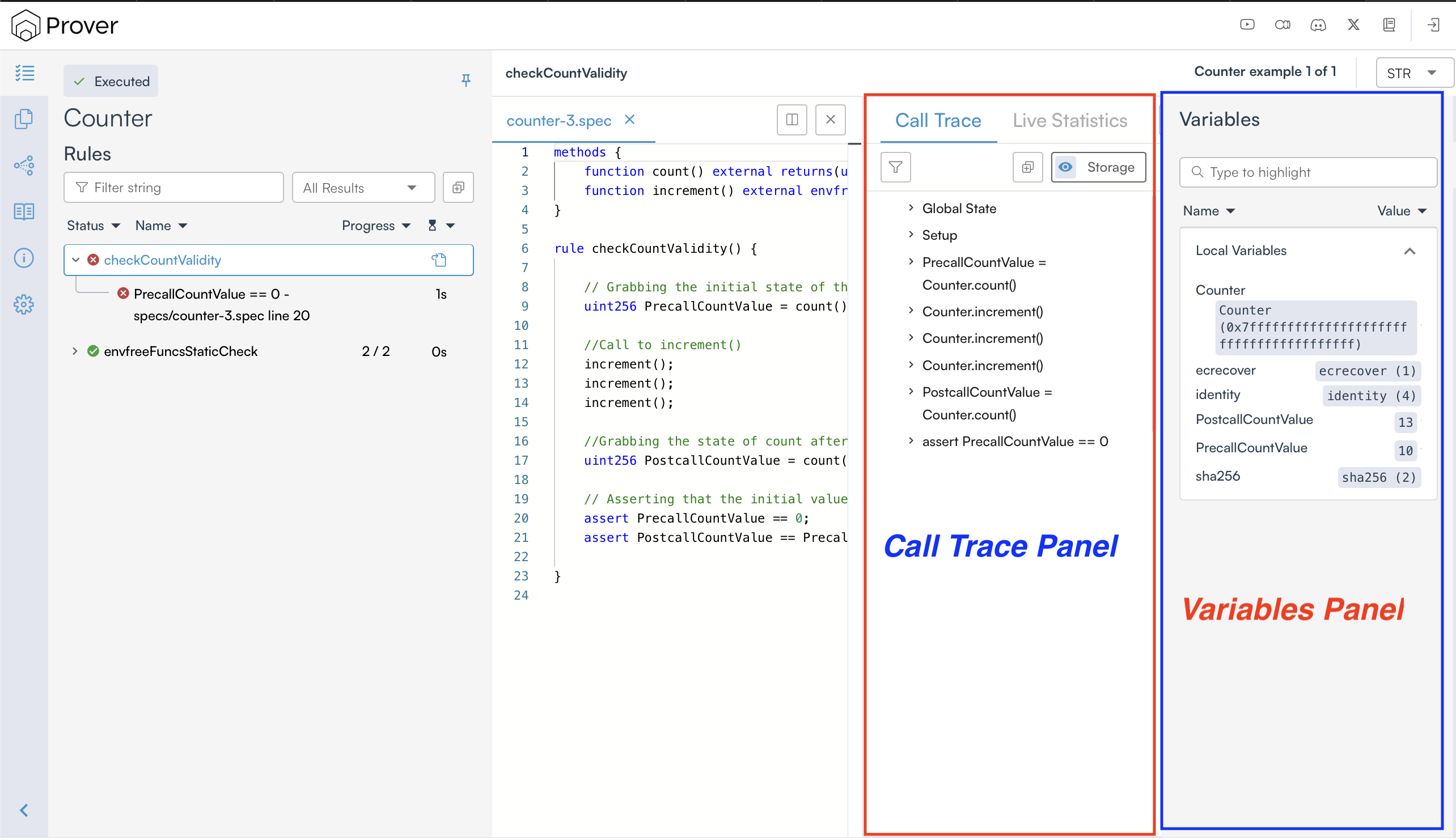

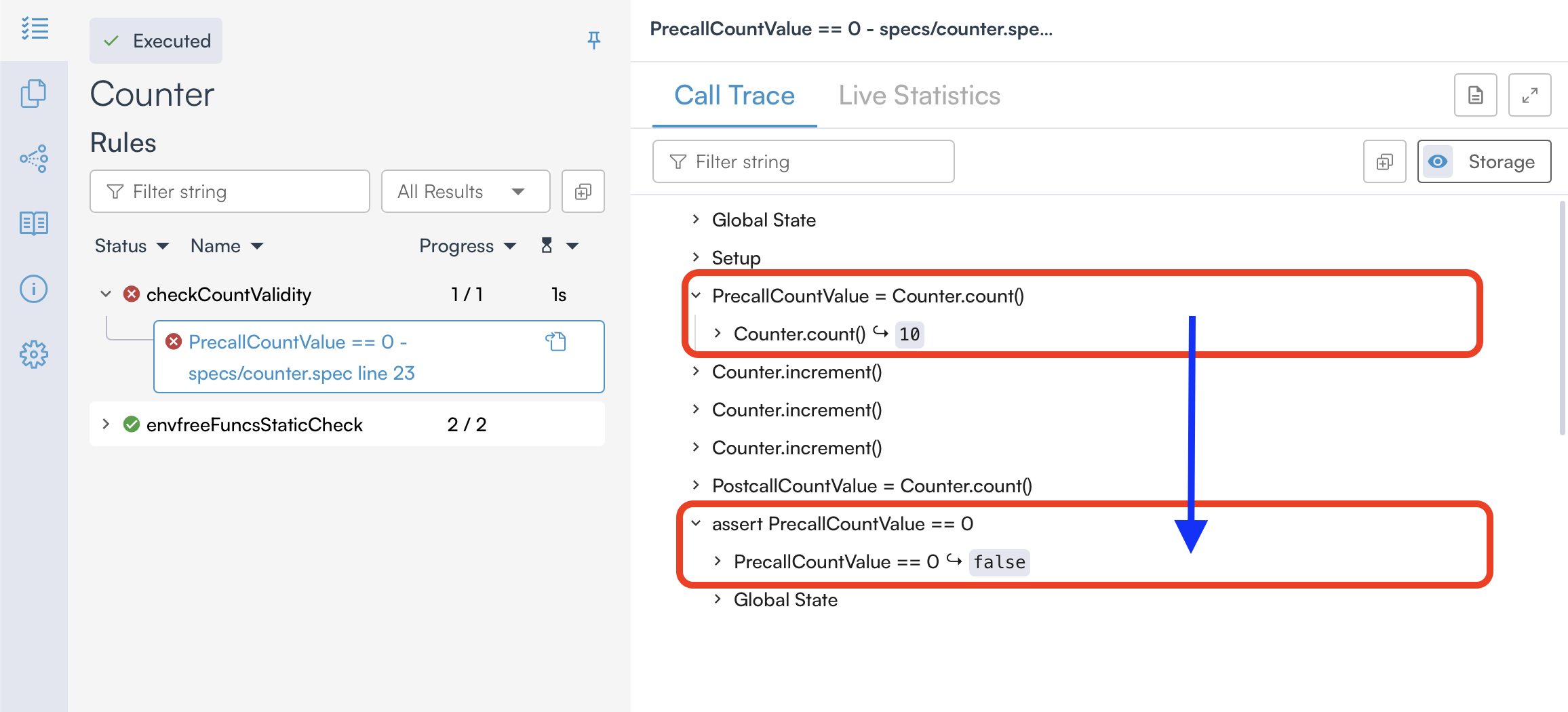

Once you do so, it shows the values of the rule’s parameters and variables (on the right-hand side), and a call trace (in the middle), as shown below.

While investigating a violation, the call trace is extremely helpful as it provides detailed information about the state variables at the beginning of the rule execution and also tracks updates to those variables throughout the execution, as shown below:

In the counterexample provided by the Certora Prover, we can clearly see that our rule failed verification because the rule expected count to start at 0, but instead it started at 10, which caused assert PrecallCountValue == 0 to fail.

This raises an important question: Why is count set to 10 instead of the expected default of 0? To understand this, we need to understand how Solidity and CVL handle uninitialized variables differently.

Why Is the count Value Set to 10 Instead of 0?

As we know, if a Solidity smart contract doesn’t explicitly initialize a state variable, it is automatically assigned a default value based on its type. For example:

- For

uint256, the default value is0. - For

bool, the default value isfalse. - For

address, the default value is the zero address.

Unlike Solidity, CVL does not automatically assign default values to variables. Instead, uninitialized variables in CVL remain unconstrained, meaning they can take on any possible value within their defined range during verification. This ties into a crucial concept: CVL rules do not start verification from the contract’s specific initial deployment state (like Solidity execution often assumes), but rather from an arbitrary state. This is a key difference and a fundamental aspect of formal verification.

Due to this behavior, the initial value of count was set to 10 during verification, which caused the rule to fail since we expected count to start at 0.

Understanding the Use of require

As observed above, the Prover assigns arbitrary values to state variables during the verification process, which can lead to unexpected initial values and cause assertions to fail if the rule assumes Solidity’s default values.

In such cases, we may want to explicitly define constraints on state variables in our verification setup, ensuring they start with the expected values before executing the rule. This is where the require statement in CVL becomes useful.

The require statement in CVL is used to specify preconditions for a rule, ensuring that certain conditions are met before the rule is considered valid.

When a require statement is included in a rule, it acts as a filter that tells the Prover to ignore any execution paths where the specified condition does not hold. This means the Prover will only consider scenarios in which the require expression evaluates to true, effectively excluding all others from analysis.

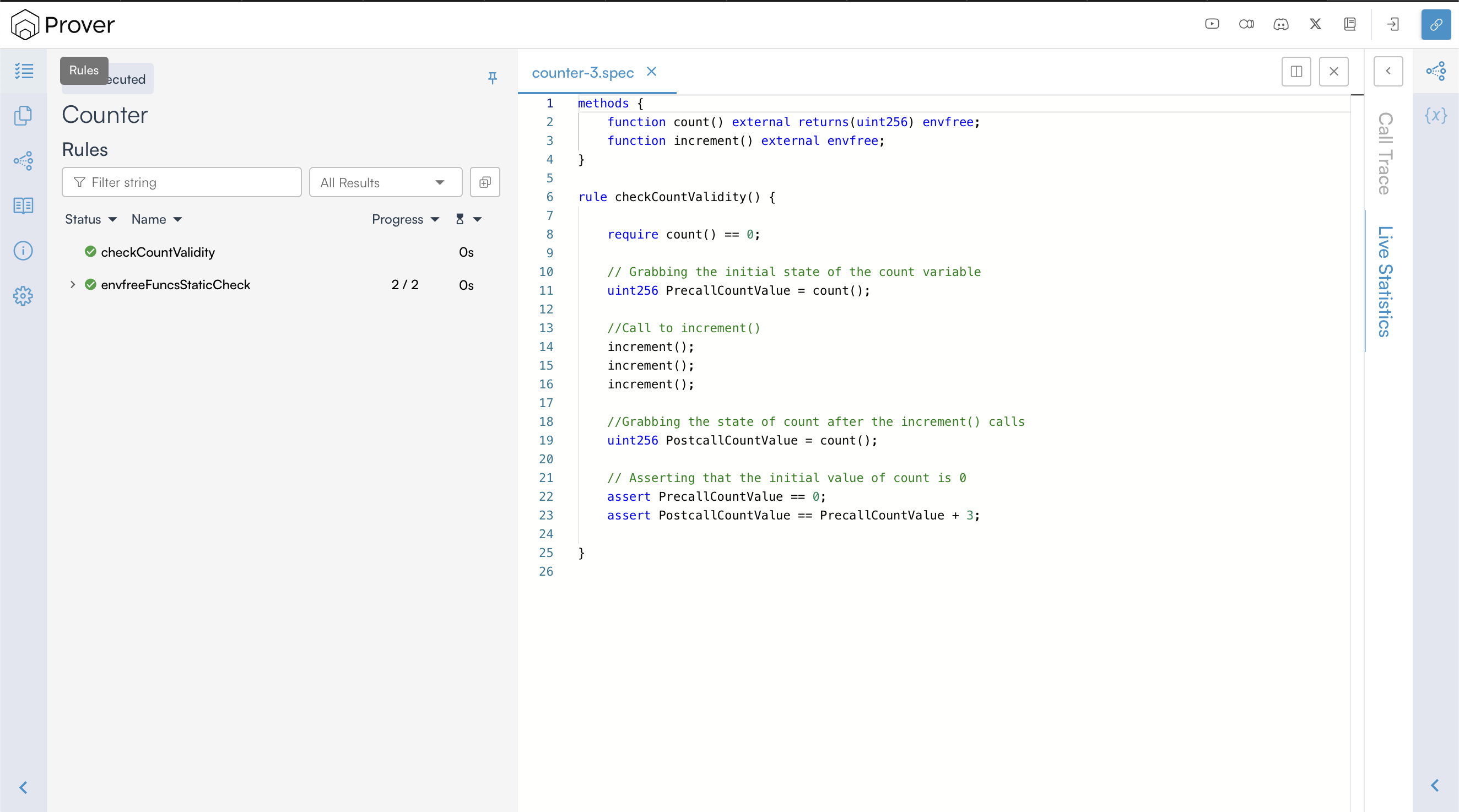

For example, we can use the require statement in our checkCountValidity rule to constrain the initial value of count to zero, as shown below:

rule checkCountValidity() {

// We just added this

require count() == 0;

// Grabbing the initial state of the count variable

uint256 PrecallCountValue = count();

//Call to increment()

increment();

increment();

increment();

//Grabbing the state of count after the increment() calls

uint256 PostcallCountValue = count();

// Asserting that the initial value of count is 0

assert PrecallCountValue == 0;

assert PostcallCountValue == PrecallCountValue + 3;

}

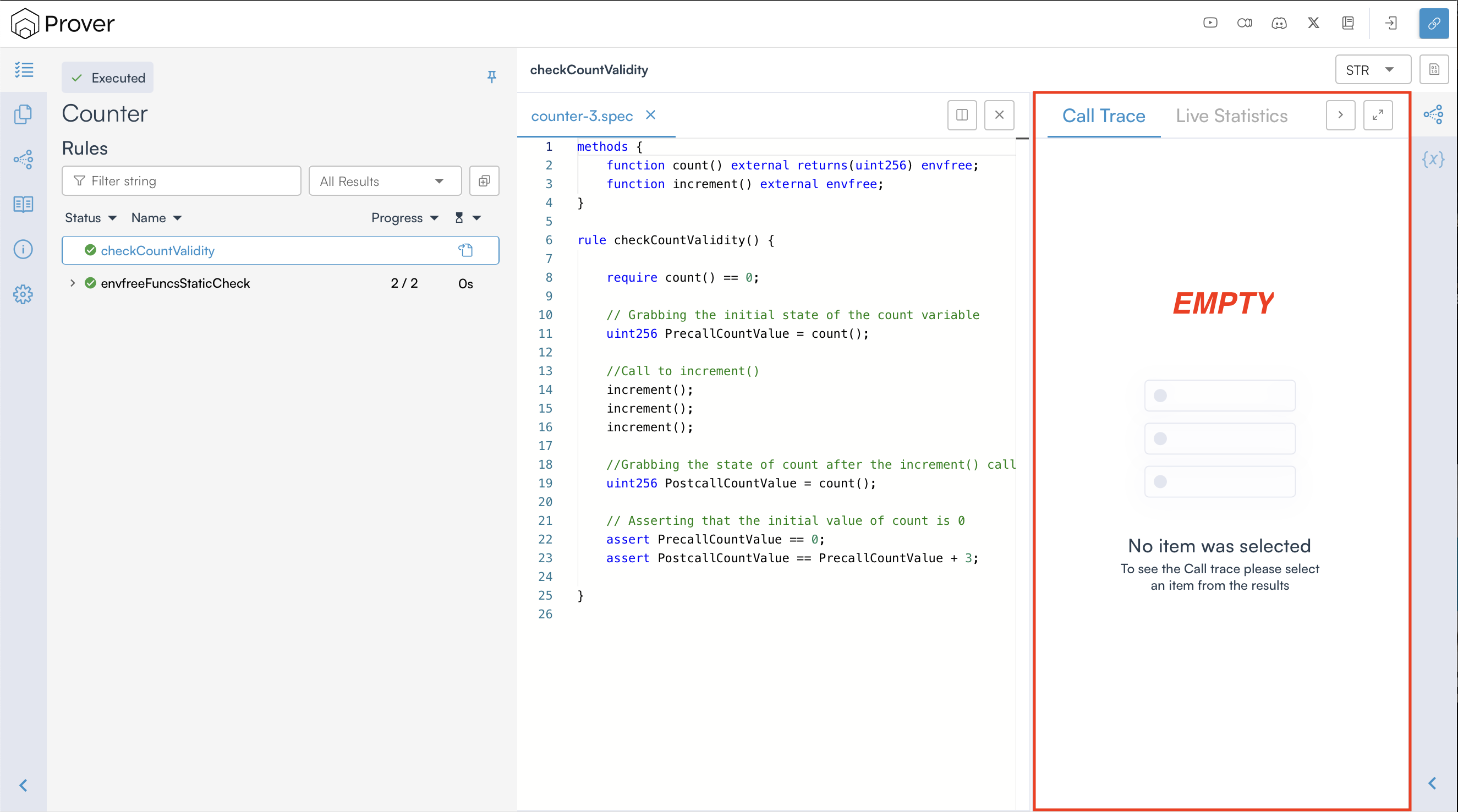

If you re-run the Prover with the above change and open the verification link printed in your terminal, you will get a verified rule, as shown below.

This time, we can see that the Prover has successfully verified our rule. This is because, with the require constraint, the prover will ignore any execution path where the initial value of count is not zero.

By default, the Prover does not provide a call trace for a verified rule because there can be an extremely large number of valid execution traces that satisfy the rule’s conditions. Since a verified rule confirms that no counterexamples exist, generating and displaying all possible valid traces would be both unnecessary and impractical.

Understanding the Use of satisfy

As mentioned earlier, the Prover does not generate a call trace when a rule is successfully verified. However, CVL offers the satisfy statement, which allows you to produce an execution trace that meets all conditions enforced by require and assert statements. This is especially useful when you want to confirm whether a specific scenario can occur within the contract’s logic.

For example, we can write a rule that uses the satisfy statement to verify:

- That there exists at least one execution path where a user can fully withdraw their liquidity after depositing and minting LP tokens.

- That there exists at least one execution path where a borrower’s position is liquidated if their collateral value drops below a specified threshold.

When a rule includes the satisfy statement, the Prover checks whether at least one valid execution path satisfies the condition. While there may be multiple such paths, only one satisfying trace is generated—if found. Based on the outcome, the rule is classified as follows:

- Verified Rule: The Prover reports the rule as verified if at least one valid execution satisfies the satisfy statement.

- Violated Rule: The Prover reports the rule as violated if no execution path satisfies the satisfy statement.

Using satisfy In a Rule

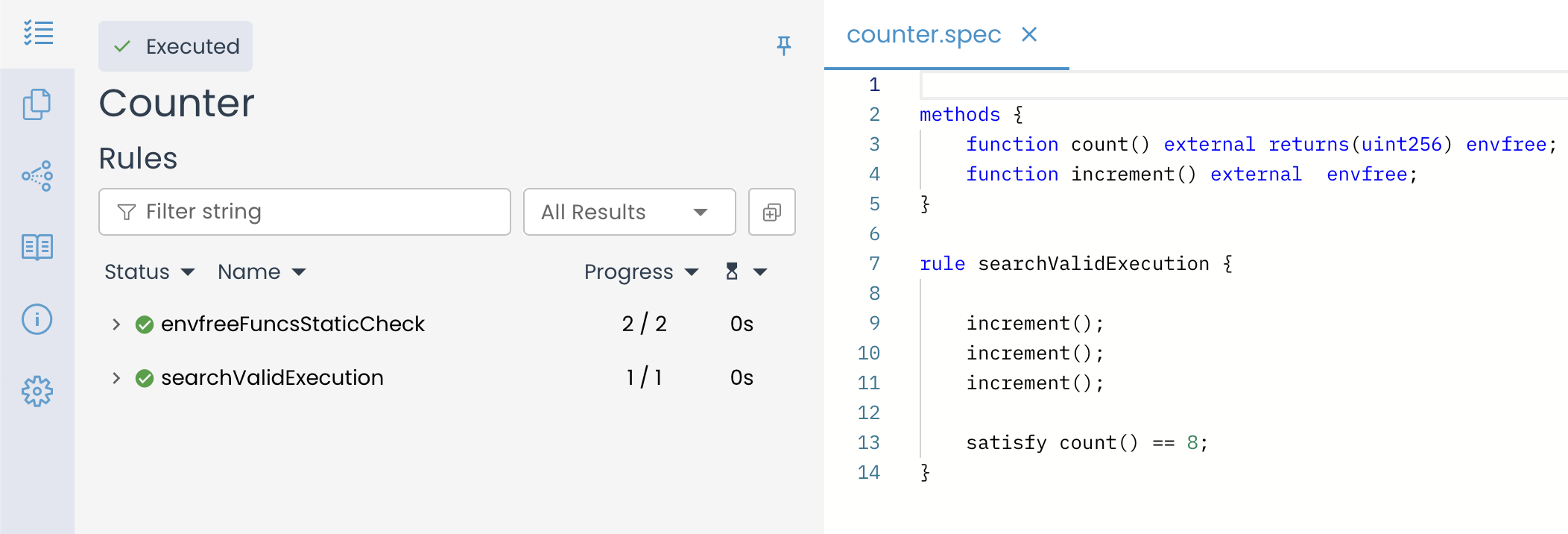

To understand how the satisfy statement works, consider the specification below that has a rule searchValidExecution() that ends with a satisfy statement.

methods {

function count() external returns(uint256) envfree;

function increment() external envfree;

}

rule searchValidExecution {

increment();

increment();

increment();

satisfy count() == 8;

}

Since the rule searchValidExecution ends with a satisfy statement, it instructs the Prover to explore possible execution paths and determine whether there exists a sequence of three increment() calls that would result in count() reaching a value of 8. If it finds such a path, the Prover reports the rule as verified. Otherwise, it reports it as violated.

To check whether the rule searchValidExecution holds, run the Prover and open the verification link in a browser to view the result.

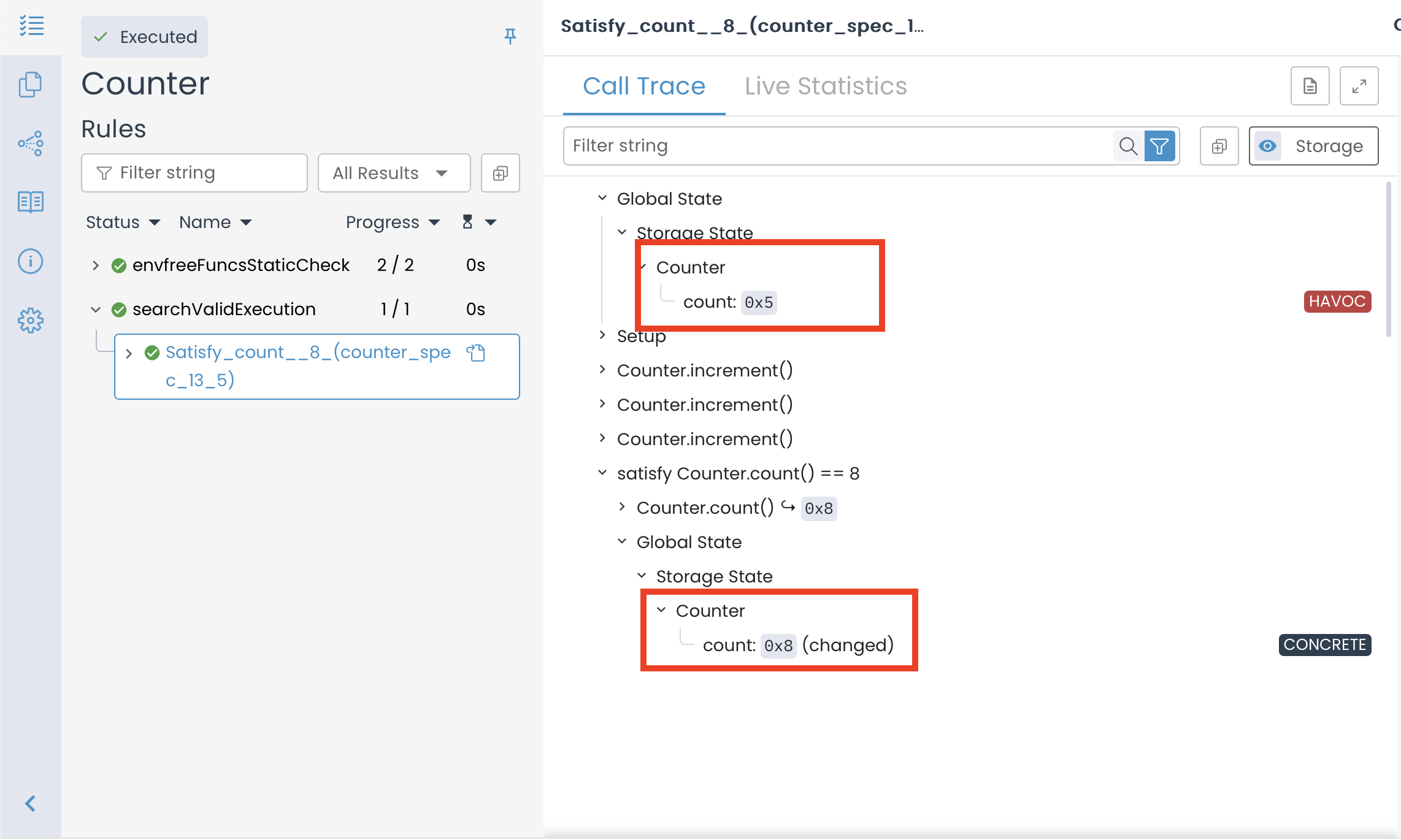

The results above show that the Certora Prover has successfully verified the rule. This means it found at least one execution path that satisfies the satisfy statement. Specifically, the Prover identified a state where count() reaches 8 after three successive calls to increment().

This outcome aligns with expectations because, ideally, the value of count() can reach 8 after three successive increment() calls if the initial value is 5 (assuming each call increases the count by 1). Since the rule seeks a valid execution path, the Prover confirmed its existence, leading to successful verification.

Using the Prover to Solve and Verify Systems of Linear Equations

Because the Prover evaluates only a single execution path when processing a rule containing a satisfy statement, it functions as a solver, determining input values that satisfy the given constraints. To demonstrate this capability, let’s use satisfy to find a solution to a system of equations.

For example, consider the following equations:

Now, suppose we want to find integer values of and that satisfy both equations. To achieve this, we first need to define a Solidity function that encodes the system of equations**:**

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Math {

function eqn(uint256 x, uint256 y) external pure returns (bool) {

return (2 * x + 3 * y == 22) && (4 * x - y == 2);

}

}

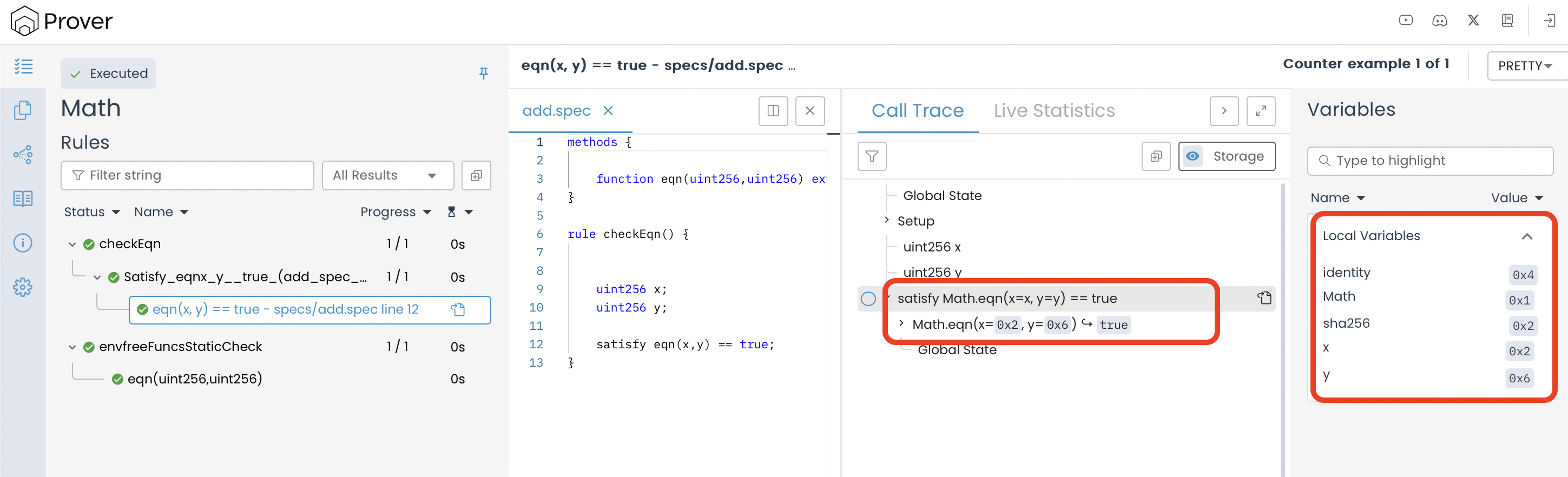

Once we define the Solidity function, we can create a rule to instruct the Prover to search for valid values of and that satisfy the constraints as shown below:

methods {

function eqn(uint256, uint256) external returns (bool) envfree;

}

rule checkEqn() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

satisfy eqn(x, y) == true;

}

Alternatively, variables can be defined directly in the rule declaration instead of being declared inside the rule body, as shown below:

rule checkEqn(uint256 x, uint256 y) {

satisfy eqn(x, y) == true;

}

When the rule is executed, the Prover attempts to find values for and that make the function return true. In this case, the correct integer solution is and .

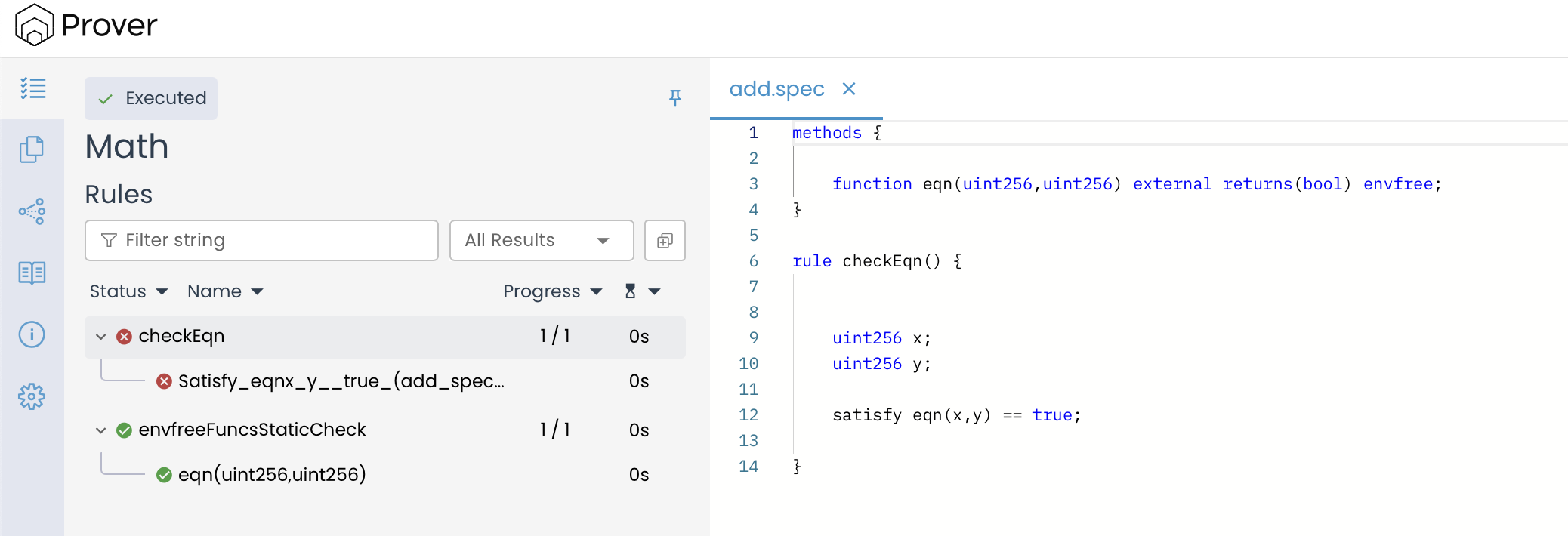

Additionally, if the equations are modified in a way that makes them inconsistent—such as defining parallel lines—the Prover will detect that no solution exists. Consider the modified system:

Since the second equation is just a multiple of the first equation but with a different constant, the system has no solutions because the two lines are now parallel and never intersect. The equivalent Solidity function is:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Math {

function eqn(uint256 x, uint256 y) external pure returns (bool) {

return (2 * x + 3 * y == 22) && (4 * x + 6 * y == 50);

}

}

When we re-run the checkEqn() rule on this modified function, the verification result indicates that the Prover correctly identifies the absence of a valid solution.

The above results highlight the Prover’s capability not only to find valid solutions when they exist but also to detect and confirm when a set of constraints is inherently unsatisfiable, such as in the case of inconsistent or parallel equations.

Key Considerations When Using satisfy Statements

There are a few important nuances to keep in mind when you use the satisfy statement in any rule:

- If a rule contains multiple

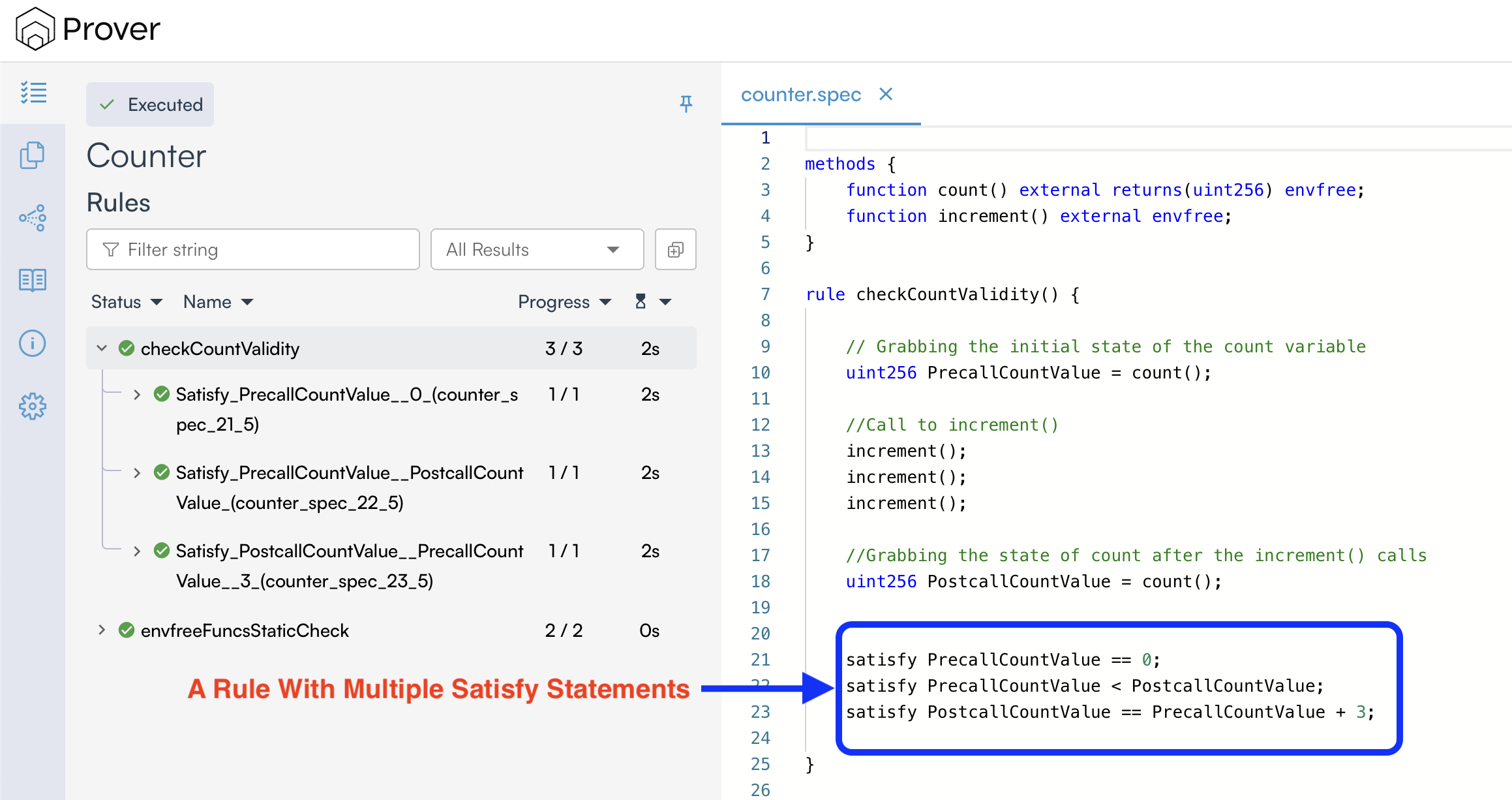

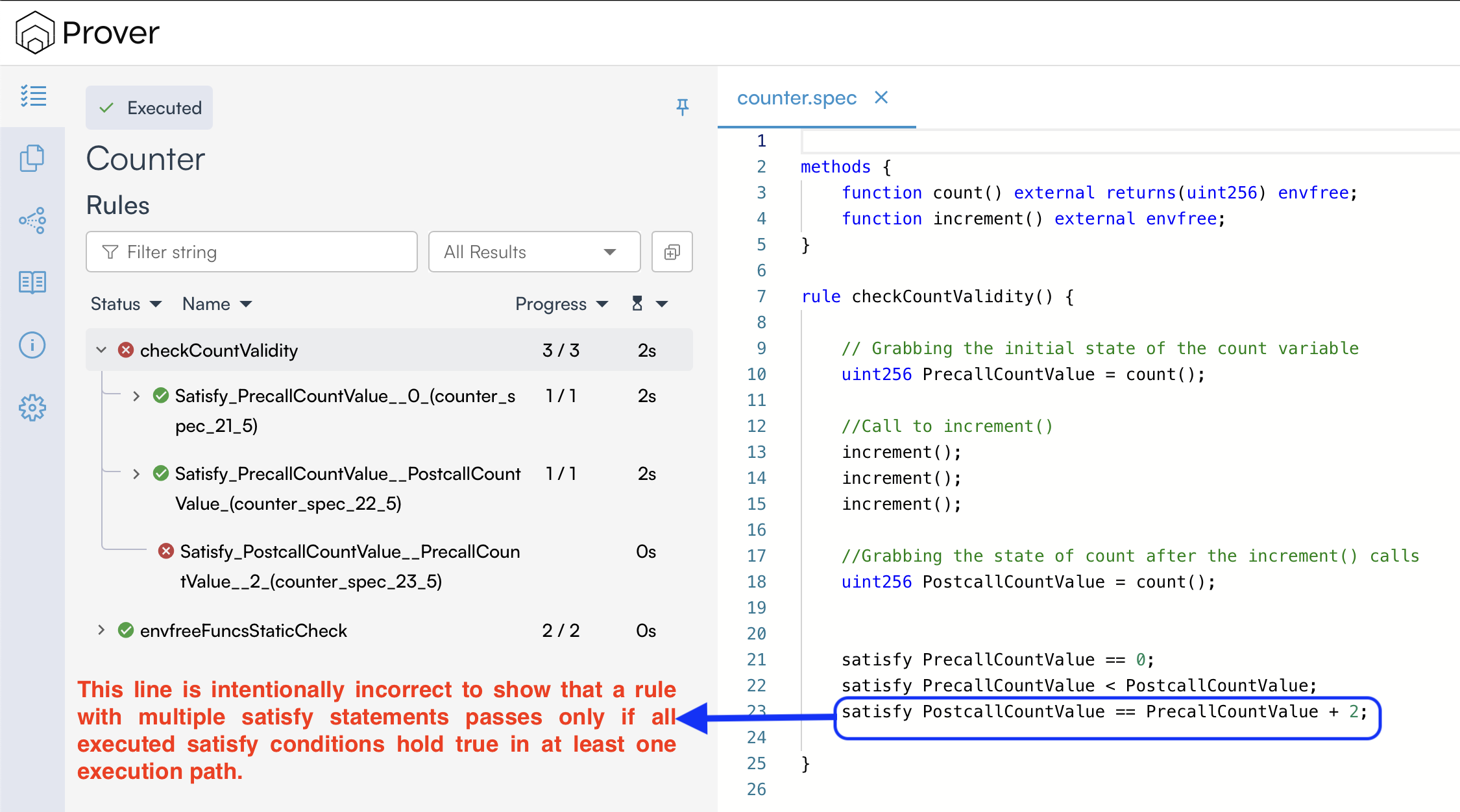

satisfystatements, the Prover will report it as verified only if all executed satisfy statements hold for at least one execution path; otherwise, the rule will be considered violated (in the default Prover mode) as shown below:

- A

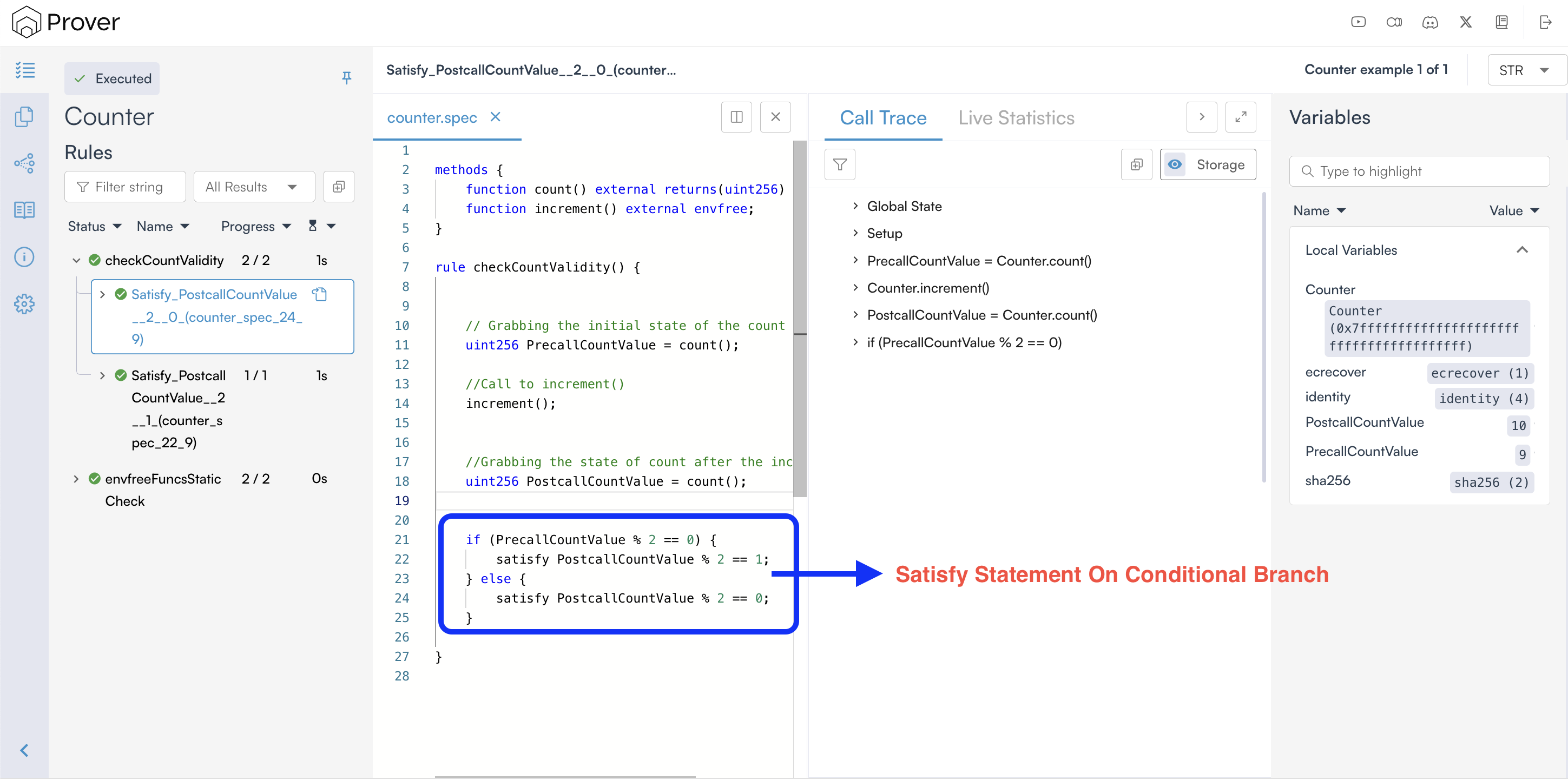

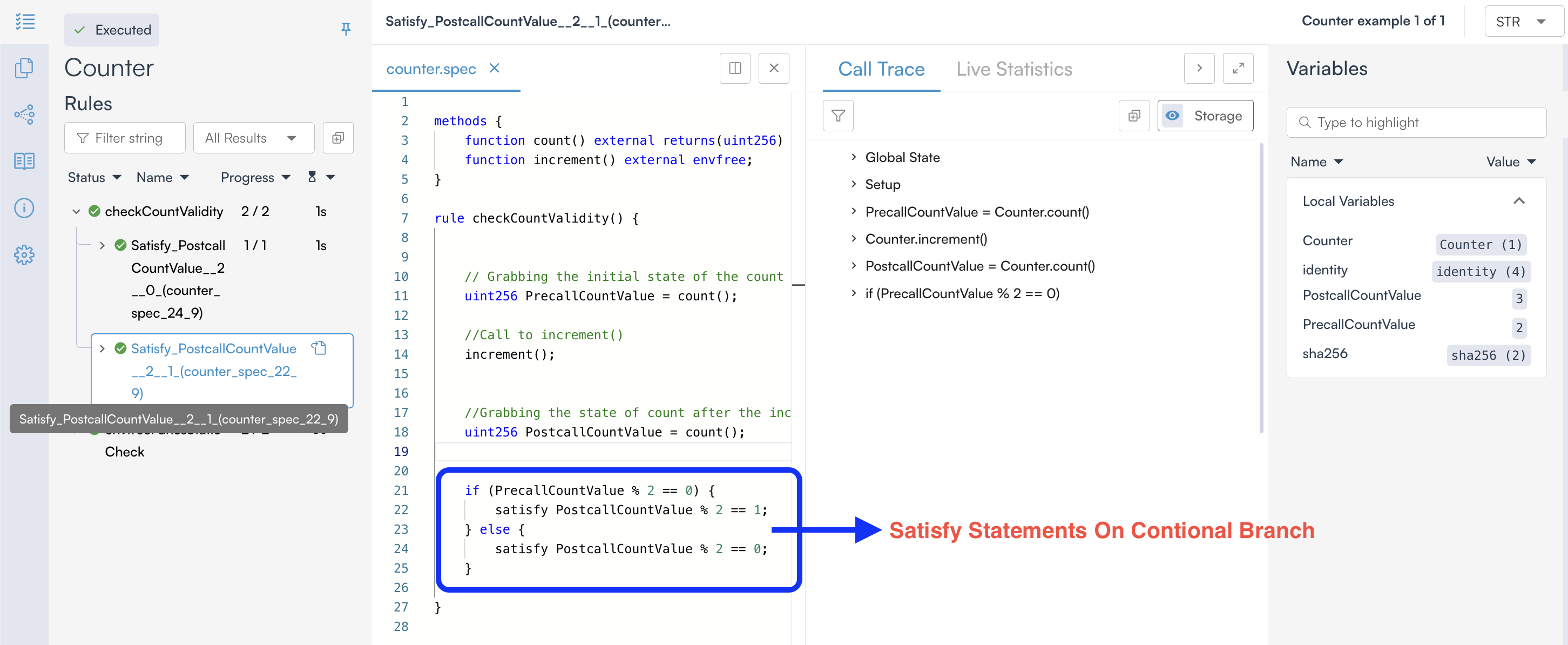

satisfystatement on a conditional branch that is not executed does not need to hold, as it is never reached during verification. The Prover verifies each execution path independently and reports the results for the executed paths, as shown below.

Difference Between assert And satisfy

At first glance, assert and satisfy statements may seem similar in functionality, as both are used to validate conditions within a rule. However, their purposes and uses are quite different, as shown below:

assert Statement |

satisfy Statement |

|---|---|

| Make sure a condition always holds in all possible executions. | Checks if there is at least one valid execution path where the condition holds. |

| If the condition ever fails, the rule is marked as violated. | If no valid execution satisfies the condition, the rule is violated. |

| Looks for counterexamples (scenarios where the rule fails). | Looks for witnesses (scenarios where the rule succeeds). |

Conclusion

In this chapter, we examined how CVL statements guide the Certora Prover during verification. We learned how assert enforces properties across all execution paths, how require constrains the states the Prover considers, and how satisfy demonstrates the existence of valid execution paths. Understanding these statements and how the Prover reasons about arbitrary states is essential for writing correct and effective CVL rules.