Up until now, we’ve either written a rule to verify specific behaviors or an invariant to verify properties that must always hold true throughout the contract’s lifetime. However, when verifying new properties, we often want to assume that other properties we’ve already proven continue to hold.

For example, when verifying a rule for token transfer, we might want to assume that the total supply still equals the sum of all balances—a property already proven by a separate invariant. Using proven invariants as assumptions prevents rules from failing due to unrealistic contract states (states that violate properties we’ve already proven can never occur).

This is where CVL’s requireInvariant statement comes in. The requireInvariant statement allows us to take an invariant we’ve already proven and use it as an assumption when verifying new rules or invariants.

In this chapter, we’ll explore what requireInvariant is, why it’s useful, and how to apply it effectively when writing rules and invariants in CVL.

Understanding the requireInvariant Statement

The requireInvariant statement is a CVL construct that allows us to inject a proven invariant as an additional condition in a rule or another invariant.

How requireInvariant Works

When a requireInvariant statement is included in a rule or another invariant, the Prover automatically assumes that the referenced invariant is already true during verification. As a result, it explores only those contract states that satisfy this condition.

Using requireInvariant in Rules and Invariants

To use requireInvariant in a rule, simply reference the invariant by name at the beginning of the rule:

rule ruleName(env e, ...) {

requireInvariant invariantName();

// rule logic here

}

When using requireInvariant inside an invariant (rather than a rule), the syntax is different. The statement is placed within a preserved block, as shown below:

invariant invariantName()

conditionExpression;

{

preserved with (env e) {

requireInvariant otherInvariantName();

}

}

Now that we understand the purpose of the requireInvariant statement and how it helps us reuse proven invariants, let’s see how it works in practice.

Revisiting the totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() Invariant

When working with ERC20 tokens, one of the most fundamental safety checks is ensuring that the sum of all balances always equals the total token supply. This invariant, often referred to as token integrity, guarantees that tokens cannot be created or destroyed unintentionally and that the sum of all individual balances equals the total supply

In the chapter titled “Verifying an Invariant Using Ghosts and Hooks”, we formally verified this critical safety property of the ERC20 implementation from Transmission11’s Solmate library using the following specification:

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

ghost mathint sumOfBalances {

init_state axiom sumOfBalances == 0;

}

hook Sload uint256 balance balanceOf[KEY address addr] {

require sumOfBalances >= to_mathint(balance);

}

hook Sstore balanceOf[KEY address account ] uint256 newAmount (uint256 oldAmount) {

sumOfBalances = sumOfBalances - oldAmount + newAmount;

}

invariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances()

to_mathint(totalSupply()) == sumOfBalances;

Let’s see how we can use the proven totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() invariant as an assumption in another rule or invariant.

Applying requireInvariant in Rules

Suppose we want to define a rule checkTransferSuccess() to verify the correctness of the transfer() function in our ERC20 contract. Specifically, we want to ensure that a successful transfer correctly updates the sender’s and recipient’s balances while leaving the total supply unchanged.

To express such a rule, we follow these steps:

- Understand the expected behavior of the

transfer()function. - Write a CVL rule to verify this behavior.

- Run verification and observe the result.

As we’ll see, the initial verification will fail—not because of a bug in the contract, but because the Prover explores unrealistic states. This will lead us to introduce requireInvariant as the solution.

Let’s put these steps into practice.

Understanding the Expectation of the transfer() Function

To define the specification for the transfer() success call, let’s first examine the implementation of the function from Solmate’s ERC20 contract:

function transfer(address to, uint256 amount) public virtual returns (bool) {

balanceOf[msg.sender] -= amount;

unchecked {

balanceOf[to] += amount;

}

emit Transfer(msg.sender, to, amount);

return true;

}

From the above code, we can see that the transfer() function moves a specified number of tokens (amount) from the sender’s account to the recipient’s account (to). The function follows this logic:

- If the sender has enough tokens: the sender’s balance decreases by

amount, and the recipient’s balance increases by the same. - If the sender does not have enough tokens: the operation reverts automatically due to arithmetic underflow, and no state changes occur.

Expressing our transfer() Call Expectation in CVL

Now that we have a clear understanding of the expected behavior of the transfer() function, we can translate it into CVL code by following these steps:

- Open the specification file: Inside your Certora project directory, navigate to the specs subdirectory and open the

erc20.specfile that we created to verify thetotalSupplyEqSumOfBalances()invariant. The file should contain the following specification:

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

ghost mathint sumOfBalances {

init_state axiom sumOfBalances == 0;

}

hook Sload uint256 balance balanceOf[KEY address addr] {

require sumOfBalances >= to_mathint(balance);

}

hook Sstore balanceOf[KEY address account ] uint256 newAmount (uint256 oldAmount) {

sumOfBalances = sumOfBalances - oldAmount + newAmount;

}

invariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances()

to_mathint(totalSupply()) == sumOfBalances;

- Add a rule: Extend the

erc20.specfile by adding a new rule block namedcheckTransferCall().

rule checkTransferSuccess() {

// we’ll fill this step by step

}

- Include the environment argument: Since our

transfer()call needs access to the transaction environment (likemsg.senderand other EVM context variables), we pass this environment as an argument of typeenv e.

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e) {

// we’ll fill this step by step

}

- Declare inputs: The

transfer()function requires two inputs: a recipient address and an amount of tokens to transfer. We declare these as local variables in our rule.

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e){

// NEWLY ADDED //

address to;

uint256 amount;

}

- Add minimal constraints to the environment: Not every input combination represents a valid scenario for verification. For example, we don’t want the caller (

msg.sender) to be the contract itself, and we don’t want to allow transfers where the sender and recipient are the same account. We addrequirestatements to exclude these invalid scenarios.

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e){

address to;

uint256 amount;

// NEWLY ADDED //

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require e.msg.sender != to;

}

- Capture the pre-call state: Before making the

transfer()call, we record the sender’s balance, the recipient’s balance, and the total supply. These values serve as a baseline against which we verify the changes after the call.

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e){

address to;

uint256 amount;

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require e.msg.sender != to;

// NEWLY ADDED //

mathint precallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint precallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint precallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

}

- Invoke the

transfer()function: We now invoke thetransfer()function using the environmente, along with the recipient addresstoand the transfer amountamount.

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e){

address to;

uint256 amount;

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require e.msg.sender != to;

mathint precallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint precallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint precallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

// NEWLY ADDED //

transfer(e,to,amount);

}

Note: We call transfer() without the @withrevert modifier—this means the rule only verifies executions where the transfer succeeds. If the transfer would revert (for example, due to insufficient balance), the Prover simply excludes that path from verification.

- Capture post-call state: After the transfer executes, we once again capture the sender’s balance, the recipient’s balance, and the total supply so we can compare them against our expectations.

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e) {

address to;

uint256 amount;

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require e.msg.sender != to;

mathint precallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint precallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint precallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

transfer@withrevert(e,to,amount);

bool transferCallStatus = lastReverted;

// NEWLY ADDED //

mathint postcallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint postcallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint postcallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

}

- Assert correctness of outcomes: Next, we encode our expectations as assertions:

- The sender’s balance should decrease by exactly

amount. - The recipient’s balance should increase by exactly

amount. - The total supply should remain unchanged (transfers move tokens, they don’t create or destroy them).

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e){

address to;

uint256 amount;

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require e.msg.sender != to;

mathint precallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint precallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint precallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

transfer(e, to, amount);

mathint postcallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint postcallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint postcallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

// NEWLY ADDED //

assert postcallSenderBalance == precallSenderBalance - amount;

assert postcallReceiverBalance == precallReceiverBalance + amount;

assert precallTotalSupply == postcallTotalSupply;

}

- Update the methods block: Previously, our methods block contained only the

totalSupply()function, since it was the only one explicitly invoked in the specification. Now, we also need to include thebalanceOf()function, as our rule references it to read account balances.

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns(uint256) envfree;

function balanceOf(address) external returns(uint256) envfree; // Add this

}

Similar to totalSupply(), the balanceOf() function does not rely on the transaction environment (for example, it doesn’t use msg.sender or msg.value). Therefore, we declare it as envfree.

Note: If you are wondering how we are using the balanceOf() function even though it doesn’t appear in the contract source, the answer lies in how Solidity handles public state variables. When you declare a variable like mapping(address => uint256) public balanceOf;, the compiler automatically generates a getter function with the signature:

function balanceOf(address) external view returns (uint256);

This getter is part of the compiled contract’s interface, even if it’s not written explicitly in the source.

Optionally, we can also include the signature of the transfer() function in the methods block. However, doing so will not improve verification performance, since this function is not envfree.

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns(uint256) envfree;

function balanceOf(address) external returns(uint256) envfree;

function transfer(address,uint256) external returns(bool);

}

Running the Initial Verification

Now that our rule checkTransferSuccess() is complete, let’s run the Prover to see if it passes verification.

To run the verification, follow the instructions below:

- Make sure your

.conffile matches the configuration below:

{

"files": [

"contracts/ERC20.sol:ERC20"

],

"verify": "ERC20:specs/erc20.spec",

"optimistic_loop": true,

"msg": "Testing erc20 functionality"

}

- Next, execute the following command in your terminal:

certoraRun confs/erc20.conf

This will send your specification and contract to the Certora Prover for verification.

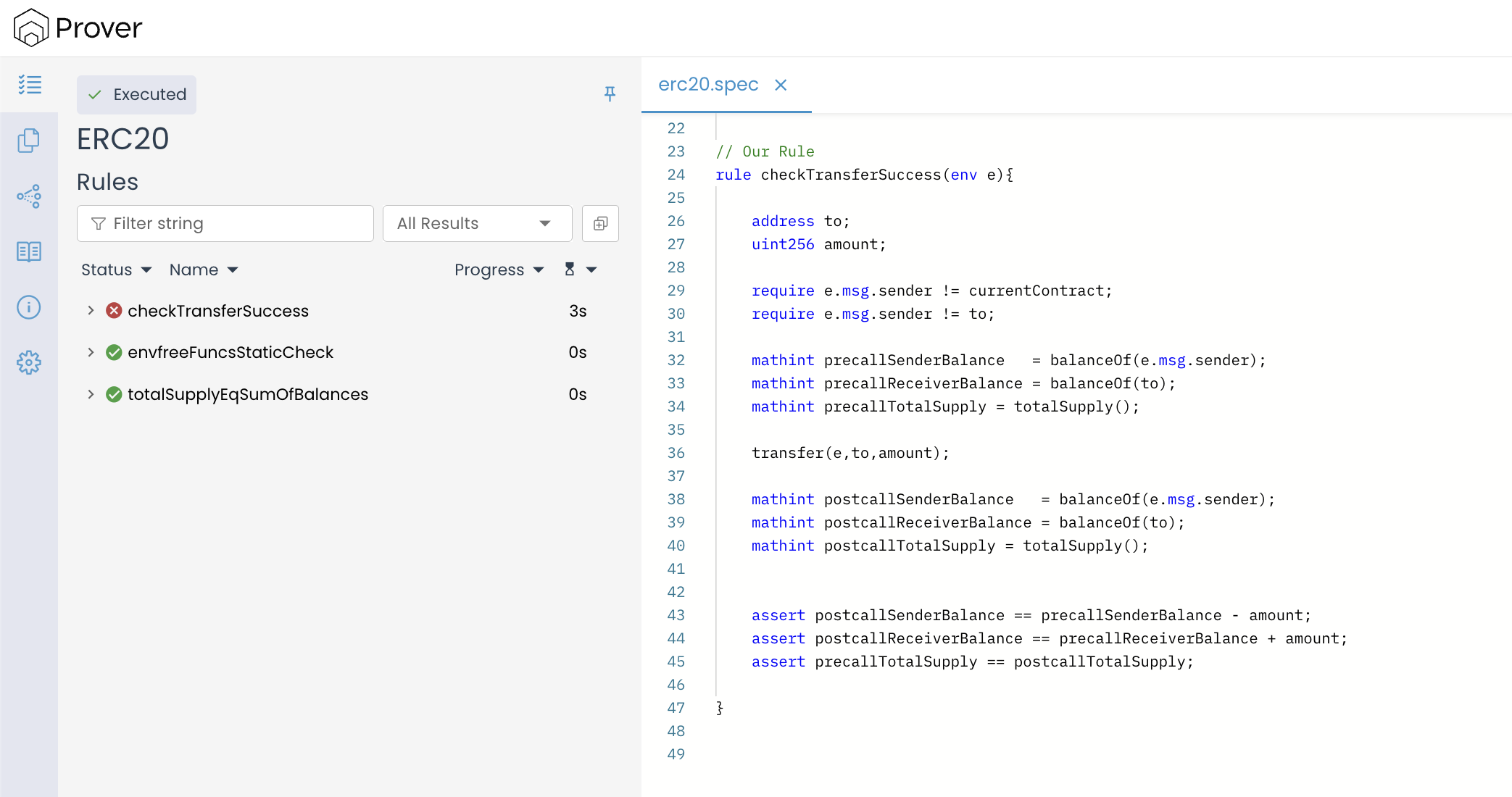

- Once the Prover finishes the run (which may take a few minutes), it will output a unique link to the verification report in your terminal. Open the link in your browser to view a result similar to the image below:

The result shows that checkTransferSuccess() has failed verification.

Understanding the Failure

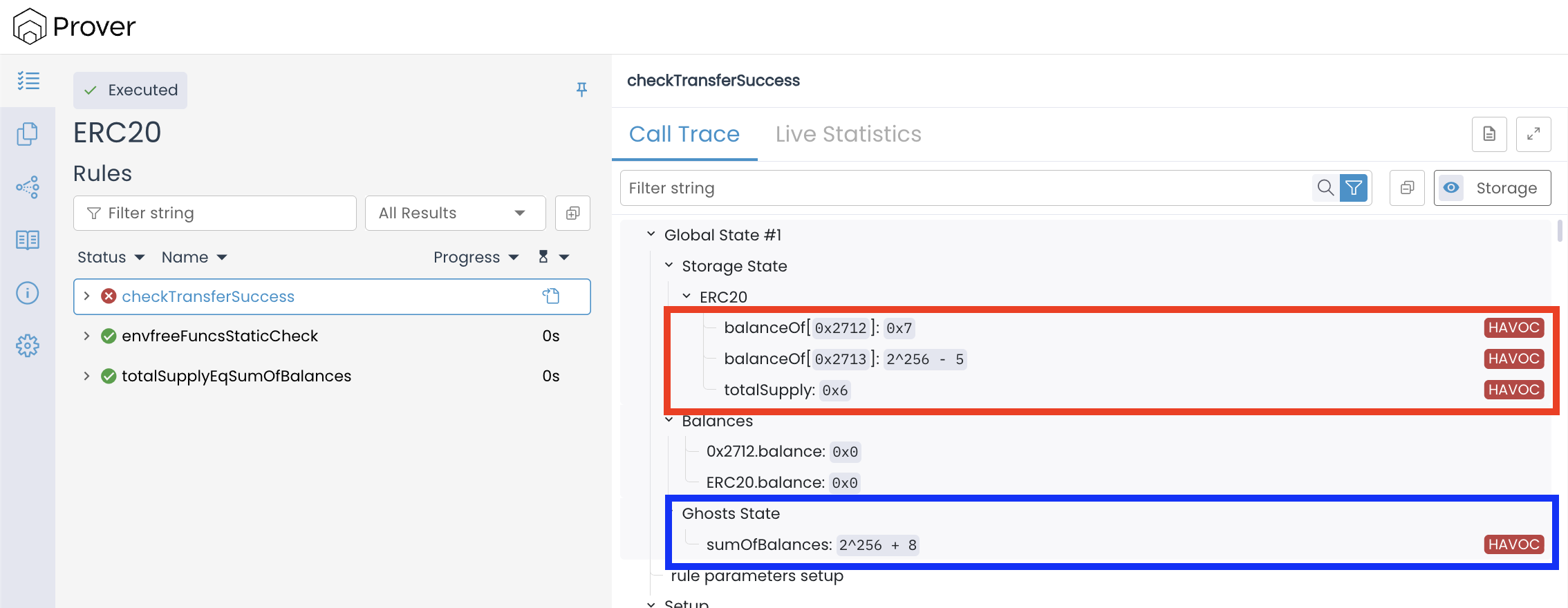

To understand why the rule failed, let’s examine the call trace. In the Storage State section under Global State #1, we can see the initial values the Prover chose:

The Prover started from a state with the following values:

Storage State (ERC20):

balanceOf[0x2712]=0x7(7 tokens)balanceOf[0x25fc]=2^256 - 5(an astronomically large value)totalSupply=0x6(only 5 tokens)sumOfBalances=2^256 + 8( Ghost State)

Notice the HAVOC labels on the right side of each value. This indicates that these values were chosen arbitrarily by the Prover.

The inconsistency is striking: one account holds 2^256 - 5 tokens, yet the total supply is only 6. Another account holds 7 tokens—one more than the total supply. Meanwhile, the ghost variable sumOfBalances is set to 2^256 + 8, which bears no relationship to either the individual balances or the total supply.

This happens because the Prover does not automatically assume that our previously proven invariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() holds when verifying a new rule. Each rule starts from a fresh symbolic state where storage variables and ghosts are assigned arbitrary values, unless we explicitly constrain them. As a result, the Prover explores states that could never occur in a real ERC-20 execution—states where the accounting relationship between balances, the ghost, and the total supply is completely broken.

When transfer() executes under these unrealistic conditions, our assertions about balance changes fail, even though the contract logic is correct.

Fixing the Failure with requireInvariant

To rule out such inconsistent states, we need to tell the Prover that checkTransferCall() should only be checked under the assumption that totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() already holds.

We do this by inserting the following line at the very beginning of the rule:

requireInvariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances();

This line tells the Prover to start verification from a state where our earlier invariant is already true. In simple terms, the Prover will only check the rule in situations where the total supply is already equal to the sum of all balances.

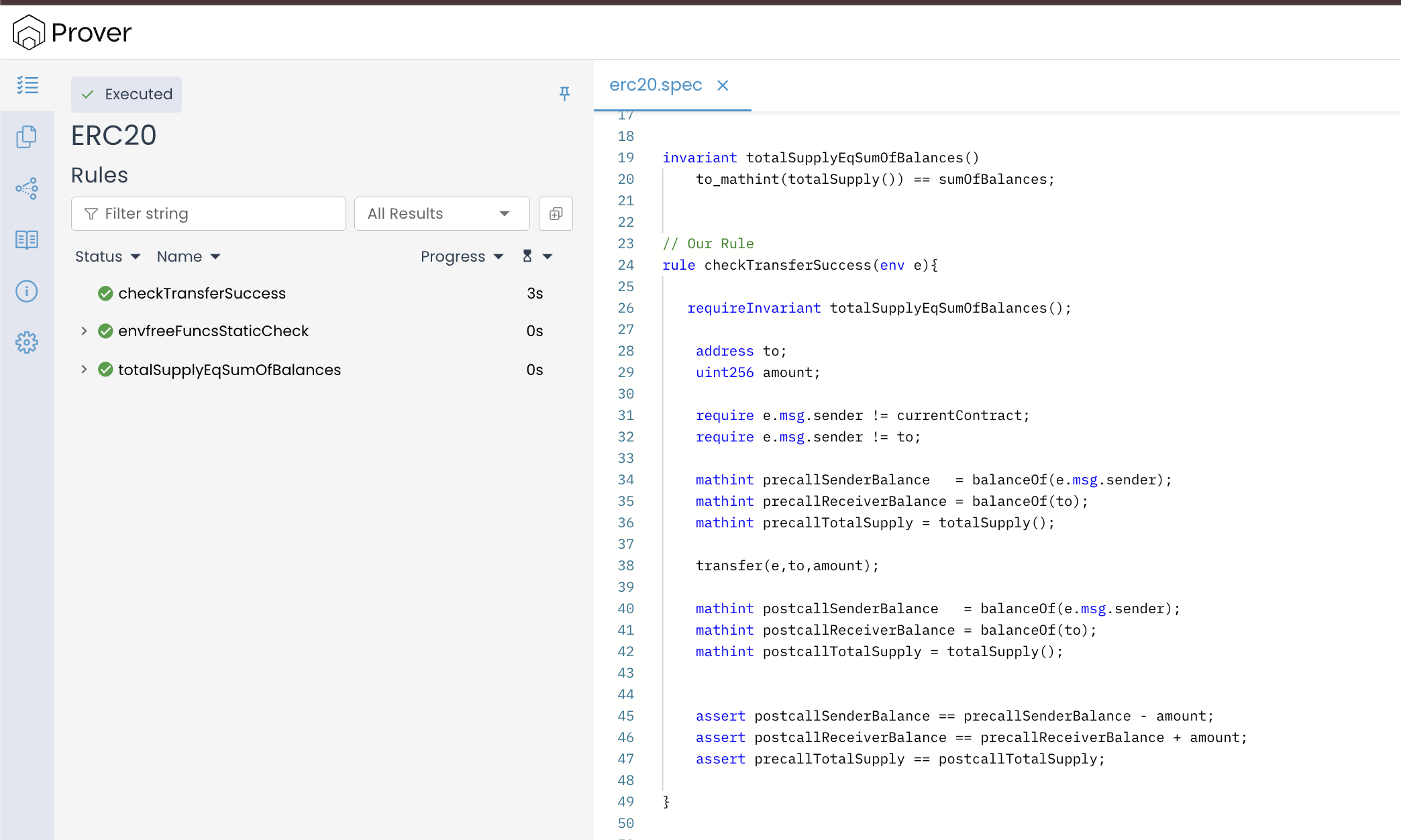

Here is the complete rule with requireInvariant added:

// Our Rule

rule checkTransferSuccess(env e){

requireInvariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances();

address to;

uint256 amount;

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require e.msg.sender != to;

mathint precallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint precallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint precallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

transfer(e,to,amount);

mathint postcallSenderBalance = balanceOf(e.msg.sender);

mathint postcallReceiverBalance = balanceOf(to);

mathint postcallTotalSupply = totalSupply();

assert postcallSenderBalance == precallSenderBalance - amount;

assert postcallReceiverBalance == precallReceiverBalance + amount;

assert precallTotalSupply == postcallTotalSupply;

}

Re-running the Verification

Now let’s run the Prover again with the requireInvariant statement in place:

certoraRun confs/erc20.conf

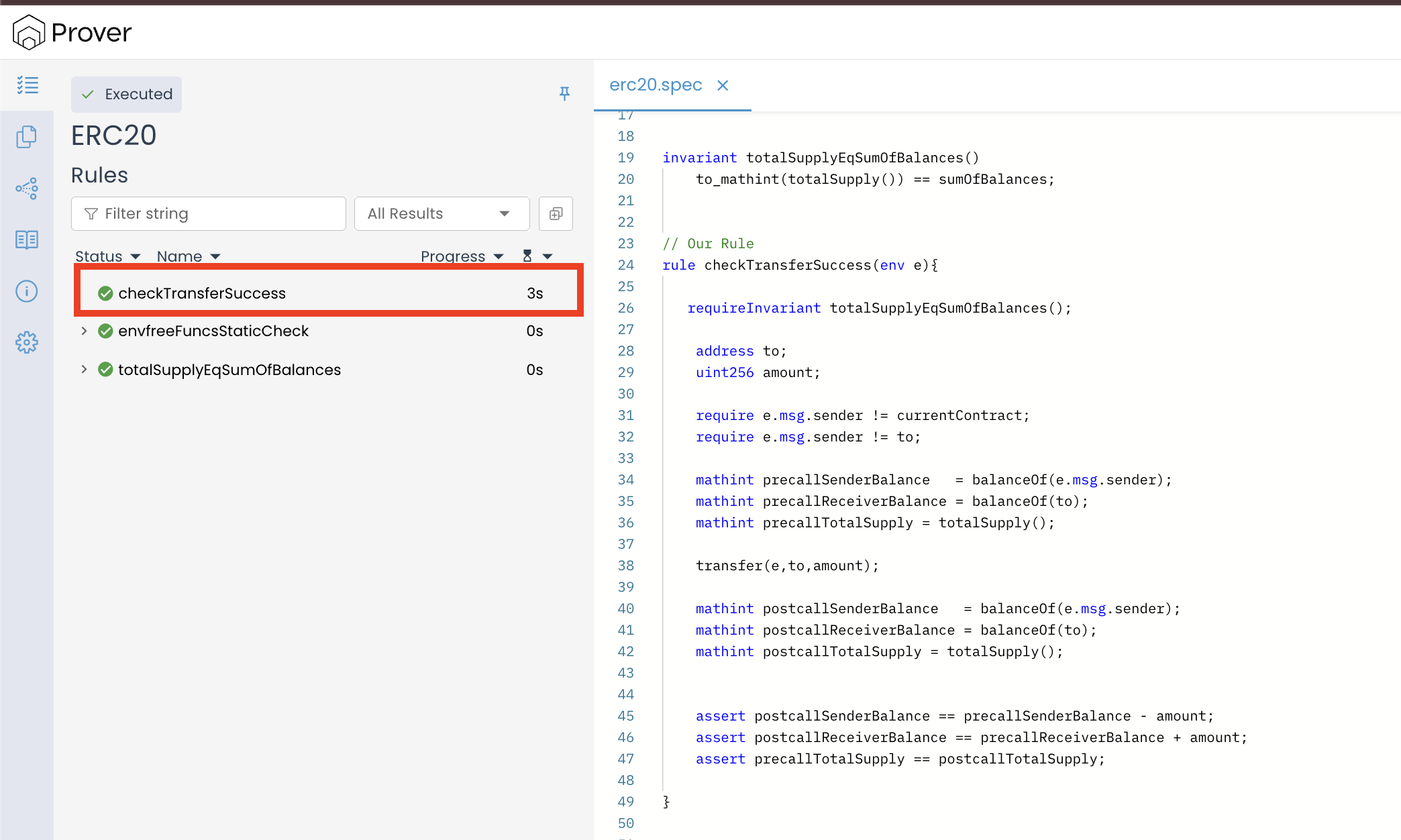

Open the verification link to view the result:

Our verification result clearly shows that the Prover has verified the rule. That means the transfer() function correctly updates balances and preserves the total supply invariant.

The example discussed above makes it clear that adding requireInvariant ensures the Prover only considers realistic contract states that respect already-proven global properties. In the next section, we’ll see how to use requireInvariant within another invariant definition.

Using requireInvariantin Invariants

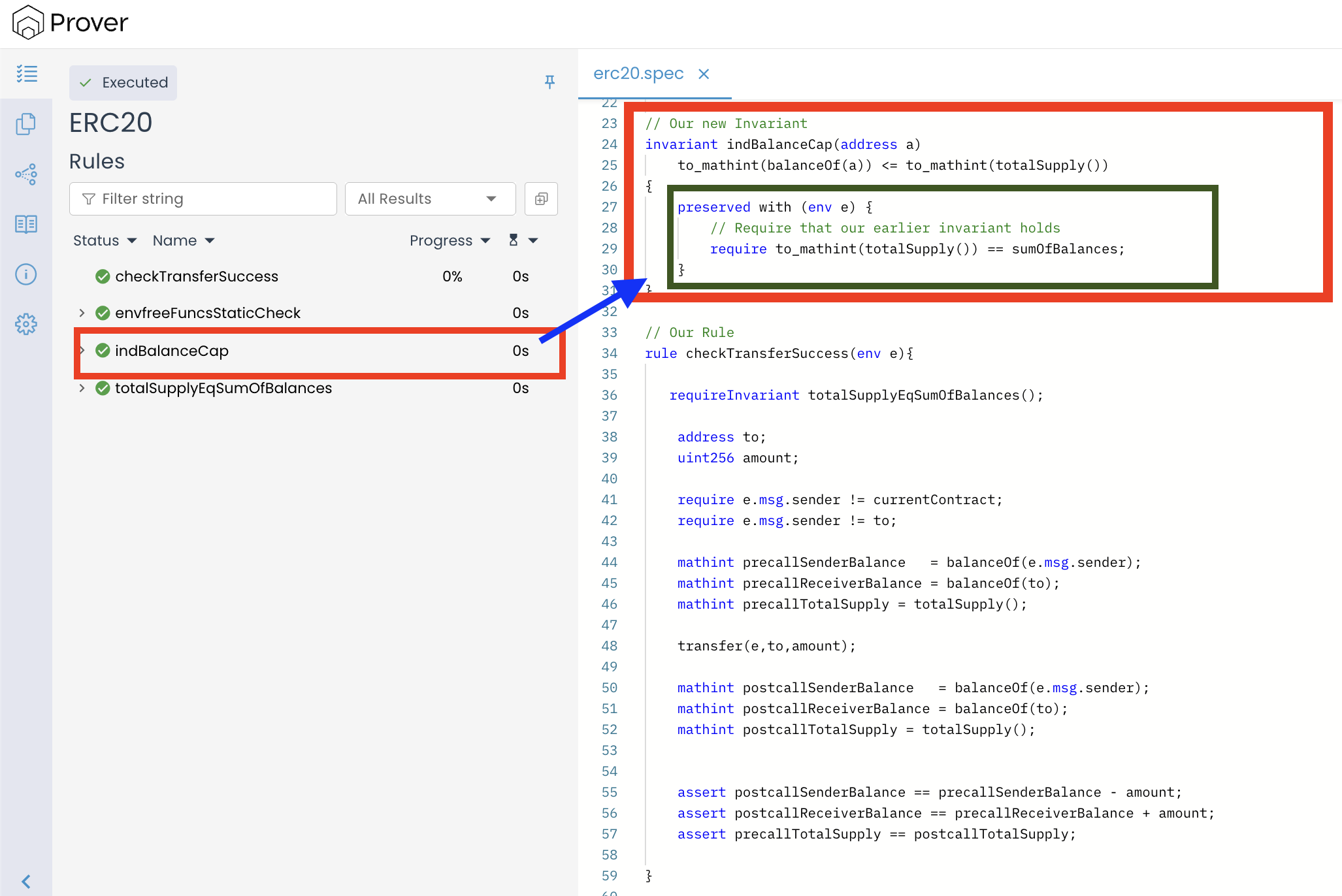

To understand how requireInvariant can be used inside the invariant construct of CVL, let’s define another invariant called indBalanceCap() inside our erc20.spec file (right below the totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() invariant).

///..

invariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances()

to_mathint(totalSupply()) == sumOfBalances;

// Our new Invariant

invariant indBalanceCap(address a)

to_mathint(balanceOf(a)) <= to_mathint(totalSupply());

//.....

This new invariant encodes a fundamental ERC-20 safety property: no account’s balance should ever exceed the total supply.

Verifying Our New Invariant

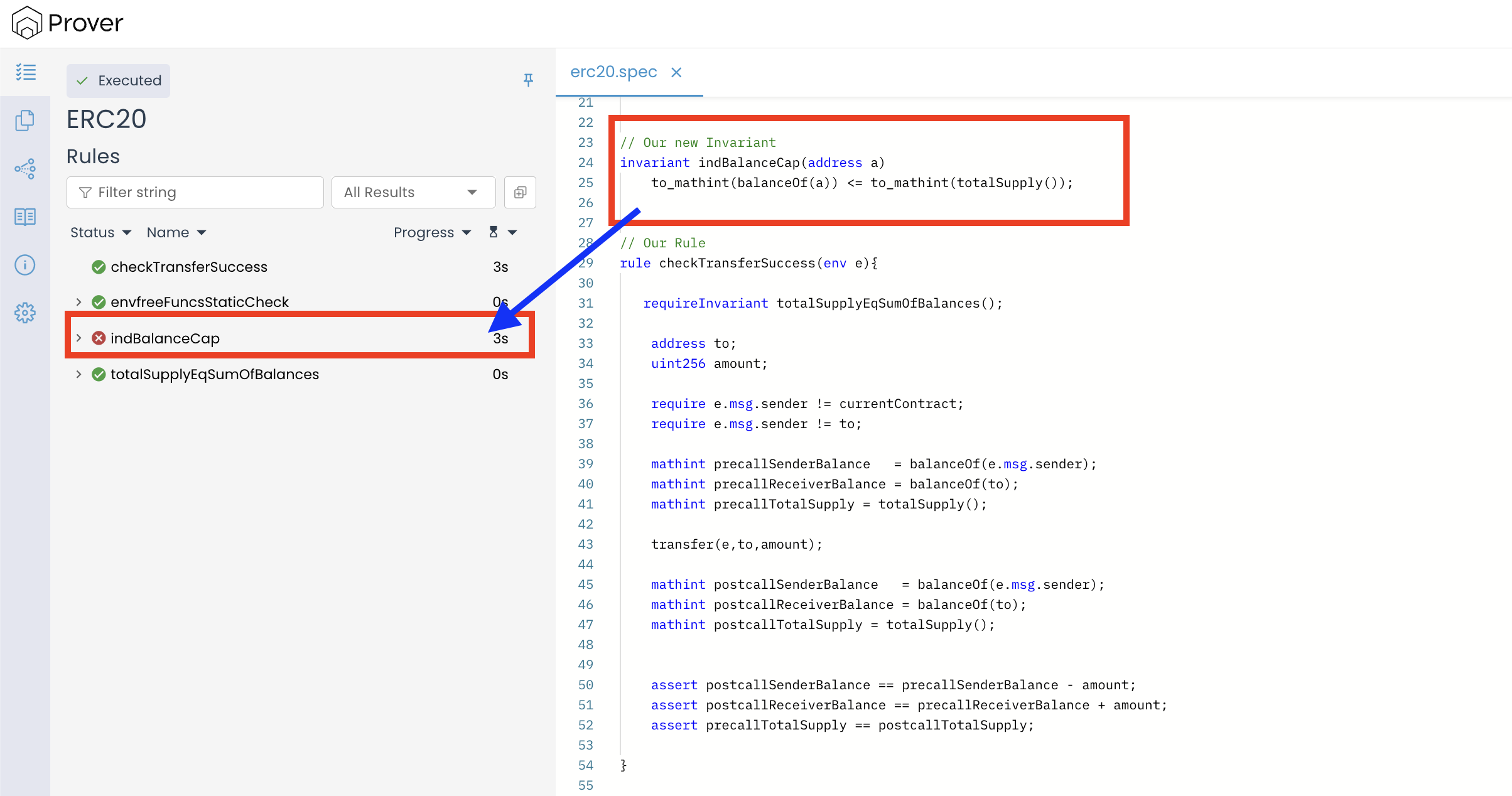

Now let’s run the Prover, and then open the verification link provided by the Prover to view a result similar to the image below:

The result above shows that our invariant indBalanceCap() has failed the verification process.

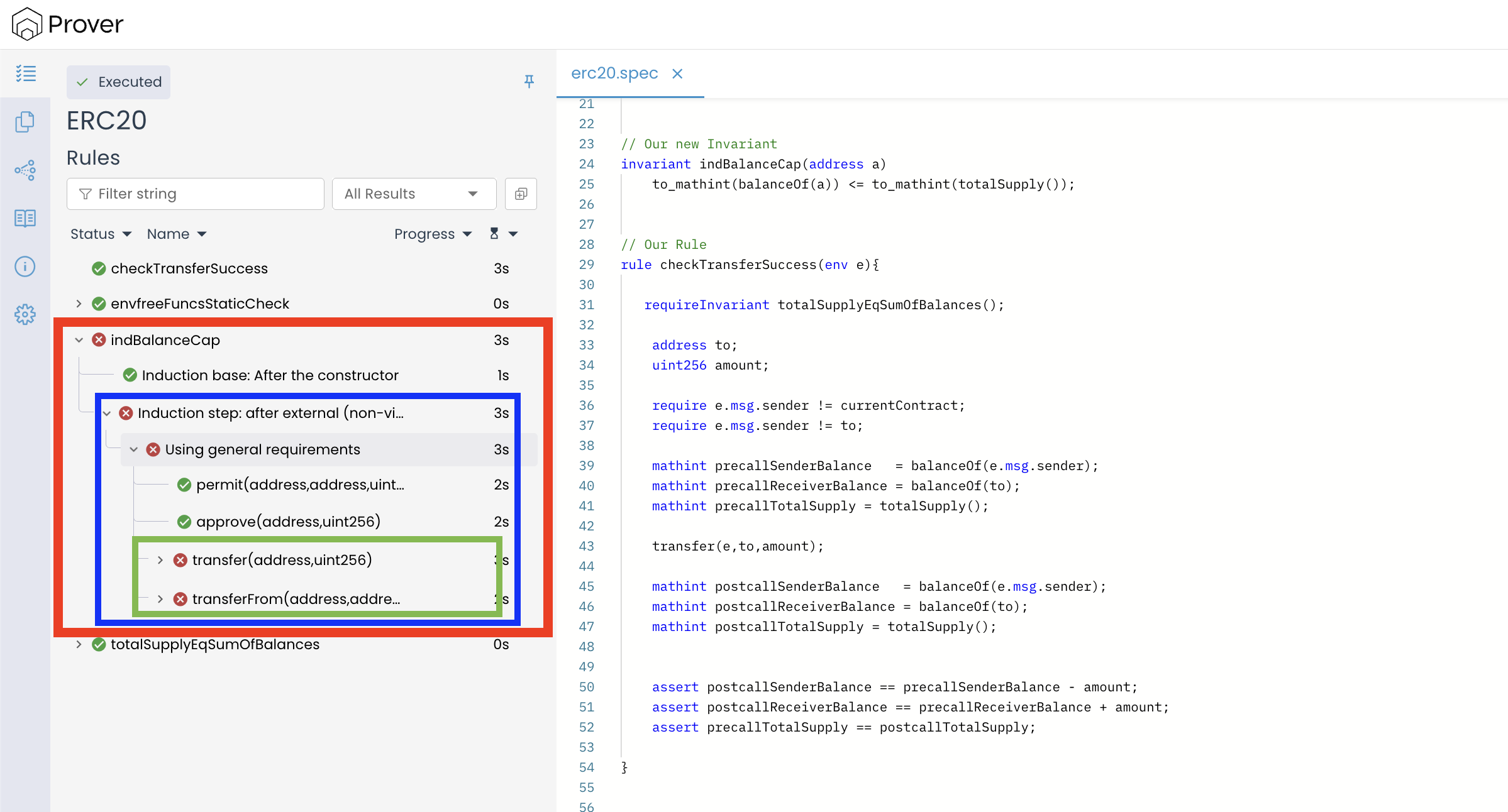

Further analysis of the Prover report shows that the invariant failed the induction check. Specifically, the Prover identified violations of the invariant through the transfer() and transferFrom() function calls, as shown in the image below:

To understand the cause of the violation, let’s analyze the transfer() call trace. (Note: transferFrom() fails for the same reason, so analyzing transfer() covers both cases)

Understanding the Violation

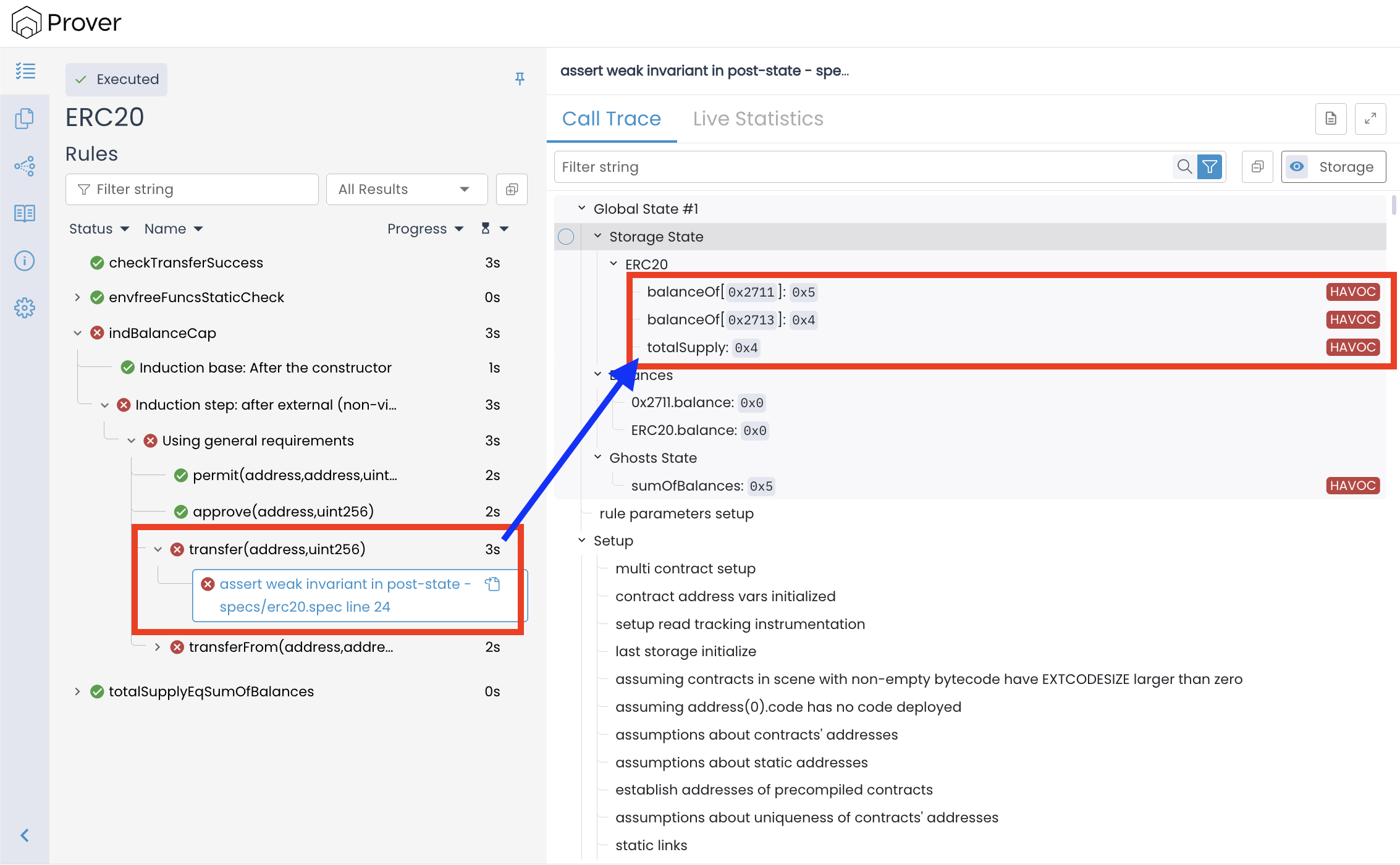

Let’s start our analysis with the Storage State section of the Prover report. This section shows the actual values of the contract’s storage variables at the initial point of verification.

In the Storage State, we can see that the individual account balances are as follows:

balanceOf[0x2711] = 0x5(account0x2711holds 5 tokens)balanceOf[0x2713] = 0x4(account0x2713holds 4 tokens)

while the totalSupply of the token is recorded as only 0x4 (i.e., 4 tokens).

Since we already proved the totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() invariant, a state like this should never occur during a real execution of the contract. That invariant says that in every valid state, the total supply must always equal the sum of all balances. But in the trace above, the balances add up to 9 while the total supply is only 4. This mismatch shows that the Prover started from a state that is not actually reachable in our ERC-20 implementation.

This happens because the Prover does not automatically assume that previously proven invariants should hold when it begins verifying a new property. Each new rule or invariant starts from a fresh symbolic state unless we explicitly connect it to earlier results. As a result, the Prover may pick an initial configuration that violates the invariant we proved before, even though such a configuration is impossible during actual contract execution

Fixing the failure with requireInvariant Statement

To rule out such inconsistent states, we need to tell the Prover that indBalanceCap() should only be checked under the assumption that totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances() already holds.

To enforce this, we explicitly import that invariant using requireInvariant, as shown below:

invariant indBalanceCap(address a)

to_mathint(balanceOf(a)) <= to_mathint(totalSupply())

{

preserved with (env e) {

// Require that our earlier invariant holds

requireInvariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances();

}

}

This way, the Prover starts from a world that already satisfies the token-conservation rule we previously proved and prevents the search space from drifting into impossible ERC-20 states.

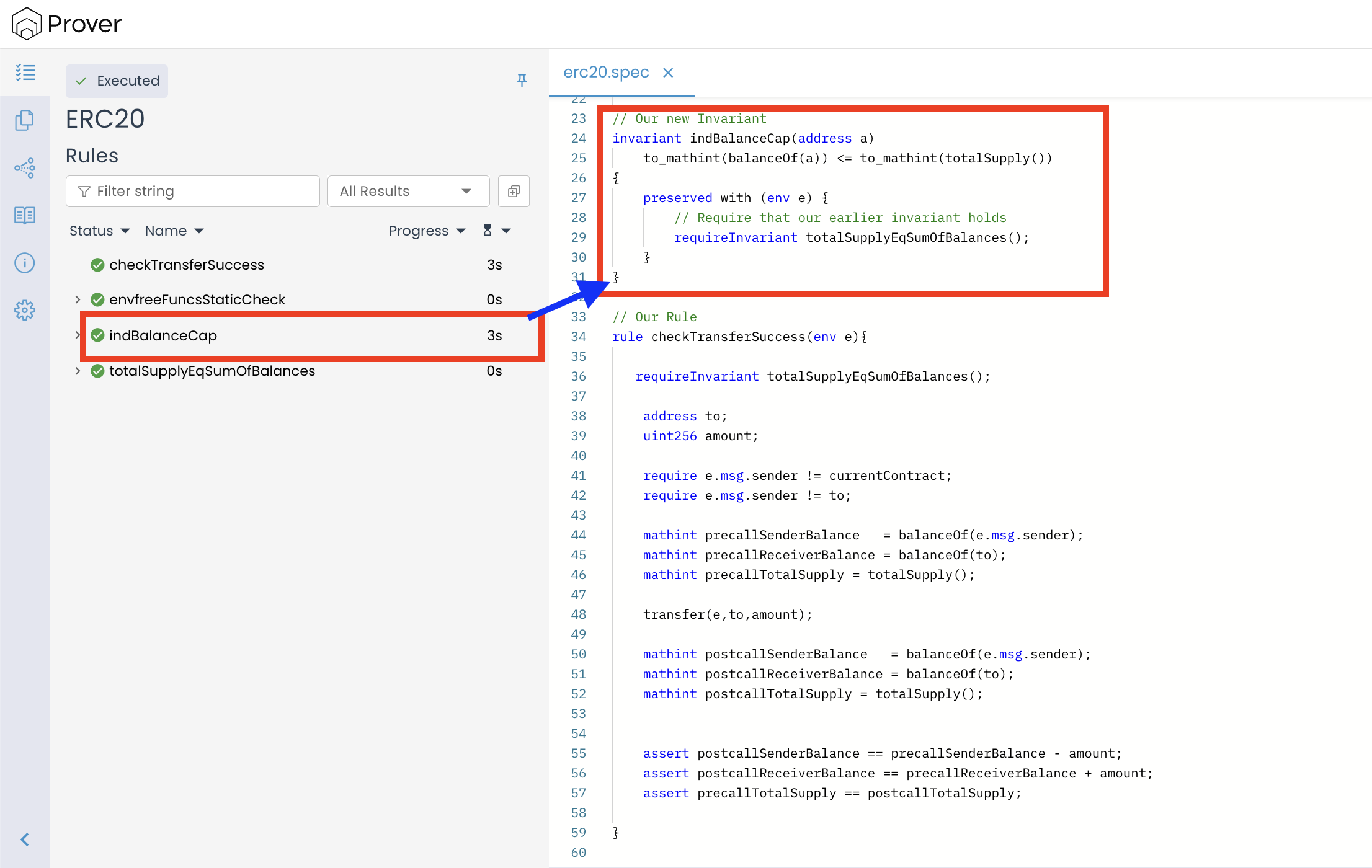

Verifying the Strengthened Invariant

Now, if we re-run the Prover with:

certoraRun confs/erc20.conf

and open the verification link, we’ll see a result similar to the image below:

We can see, as expected, that indBalanceCap() now verifies successfully. Since the Prover was restricted to states that already satisfy totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances(), it no longer encountered the impossible configurations that caused the earlier failure.

require vs requireInvariant: Same Filter, Different Guarantee

Interestingly, the indBalanceCap() invariant would also pass verification if we used a regular require statement instead of requireInvariant, as shown below:

This happens because, inside a preserved block, both require and requireInvariant serve the same operational purpose: they filter the pre-state of the induction step. In effect, both statements instruct the Prover:

“Only explore transitions that start from states satisfying this condition.”

For this reason, the following two lines place the same functional restriction on the search space:

requireInvariant totalSupplyEqSumOfBalances();

and

require to_mathint(totalSupply()) == sumOfBalances;

Both prevent the Prover from considering the inconsistent initial state we observed earlier, allowing the indBalanceCap() invariant to pass.

Why requireInvariant Is Still Preferable

Although both forms restrict the search space similarly, they differ in how reliable and principled the resulting specification is.

A requireInvariant is safer because it imports a property that the Prover has already established as true in all reachable states. A plain require relies entirely on the spec writer to state a correct condition. For example:

require to_mathint(totalSupply()) == sumOfBalances;

forces the Prover to accept this equality without checking whether it is actually true. If the condition is even slightly incorrect or incomplete, the Prover may silently ignore real counterexamples, giving a misleadingly successful verification.

Hence, the key difference is simple:

requireenforces the condition we write.requireInvariantenforces a condition already proven to be universally true.

Because of this, requireInvariant offers a safer and more principled way to reuse assumptions, while a plain require can unintentionally hide genuine violations if the condition is incorrect or incomplete.

Conclusion

This is how we can use requireInvariant to make our specifications stronger, more modular, and more efficient.

- In rules, it allows us to reuse proven invariants as prerequisites, ensuring that every execution path is checked under realistic conditions.

- In invariants, it lets us prove new properties by assuming earlier ones, avoiding meaningless counterexamples that come from inconsistent states.

The key principle is simple but powerful: prove global invariants first, then reuse them as building blocks when verifying specific behaviors or additional invariants.