Introduction

In the chapter “Introduction to Storage Hooks And Ghosts”, we covered storage hooks and ghosts with simple storage variables. We showed that hooks make it possible to track storage variables that are not directly accessible through public or external methods. We also demonstrated that when certain quantities are not explicitly stored but are required for reasoning in specifications, hooks combined with ghost variables can be used to calculate and persist those values.

Had these variables been public or externally accessible, their values could have been easily read by invoking them directly in CVL, which would allow any derived quantities to be computed as needed.

Mappings, however, are different. They are not enumerable — to access a value, one must already know the key, and there is no built-in way to retrieve “all keys” or “all values” from a mapping.

This limitation creates a major challenge for verification: many important contract properties require reasoning across all entries of a mapping. Since we cannot directly enumerate or inspect all keys, we need a mechanism to keep track of mapping changes as they happen.

In this chapter, we extend the use of Sstore hooks beyond integers, addresses, and booleans, and apply them to storage mappings — a common pattern in specifications, since many contracts rely heavily on mappings.

Sstore Hook Syntax for Mappings

Before we proceed with the code demonstrations, let’s first learn the code syntax / patterns of Sstore hooks for mappings.

Sstore hook — capture the new and old values

Here’s the Sstore hook syntax for capturing the new and old values of a storage mapping:

hook Sstore balances[KEY address user] uint256 newVal (uint256 oldVal) {

// Implement hook logic for the balances mapping where:

// - KEY is `user`

// - old (previous) value is `oldVal`

// - new (current) value is `newVal`

}

Whenever a mapping value is written to, both the old and new values can be captured.

For example, to verify that a user’s balance does not increase by more than 10, we calculate the difference between the old and new balances and assign the result to the ghost variable g_balanceDelta:

ghost mathint g_balanceDelta;

hook Sstore balances[KEY address user] uint256 newVal (uint256 oldVal) {

g_balanceDelta = newVal - oldVal;

}

The hook computes the delta (newVal - oldVal) and stores it in the ghost variable g_balanceDelta, which represents how much a user’s balance changes during that storage update.

The g_balanceDelta value can then be used to verify change limits. For example:

rule deltaNotMoreThan10() {

...

assert g_balanceDelta <= 10;

}

Sstore hook — capture new value only

We may choose to capture only the new value and omit the old value, since the latter is optional:

hook Sstore balances[KEY address user] uint256 newVal {

// implement hook logic

}

This is mostly used when the storage is simply being set and the delta (change) is not required in the verification logic.

For example, if we want to reason that a user’s balance does not exceed 2000, we only need to capture newVal and assign it to a ghost variable:

ghost mathint g_balance;

hook Sstore balances[KEY address user] uint256 newVal {

g_balance = newVal;

}

The g_balance value can then be used to verify whether a balance stays within defined limits. For example:

rule balanceDoesNotExceed2000() {

...

assert g_balance <= 2000;

}

Tracking all keys and values in a mapping is impossible without an Sstore hook

To understand why hooks are necessary for verifying properties involving mappings, let’s start with a simple contract, PointSystem, that does the following:

- Adds points to a specific user and increases the total points.

- Keeps a per-user record in the mapping

pointsOf[address]. - Tracks the overall total in the variable

totalPoints.

contract PointSystem {

mapping (address => uint256) public pointsOf;

uint256 public totalPoints;

function addPoints(address _user, uint256 _amount) external {

pointsOf[_user] += _amount;

totalPoints += _amount;

}

}

Now, let’s verify the property: “The sum of individual user points equals the total points.”

Without using an Sstore hook, one approach is to work with a limited number of users — for example, two. We read their balances directly from the mapping pointsOf, add their points, and assert that this sum equals totalPoints.

The rule below demonstrates this approach, with totalPoints and all pointsOf values starting at zero:

rule sumOfUserPointsEqualsTotalPoints() {

address account1; address account2;

uint256 amount1; uint256 amount2;

require account1 != account2;

require pointsOf(account1) == 0 && pointsOf(account2) == 0; // points per user starts at zero

require totalPoints() == 0; // total starts at zero

addPoints(account1, amount1);

addPoints(account2, amount2);

assert to_mathint(totalPoints()) == pointsOf(account1) + pointsOf(account2);

}

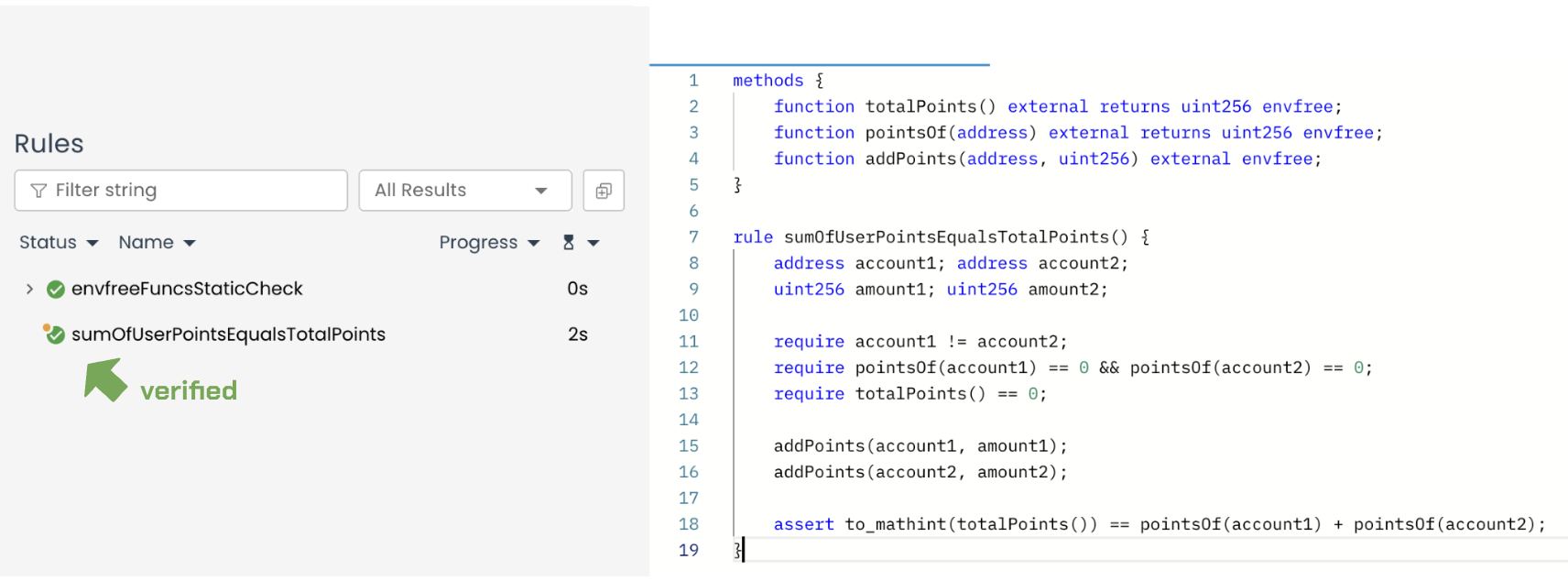

In this Prover run, we see that the property is verified:

Prover run: link

By asserting equality using only two users (even if more are added manually by declaring additional account variables), the property is limited to that subset of accounts. This is not the exact property we want to verify, since many other users may exist in the mapping whose points are excluded from the check.

Now, let’s improve the rule. Let totalPoints and user points (pointsOf[address]) start at any value instead of zero by removing the preconditions require pointsOf(account1) == 0 && pointsOf(account2) == 0 and require totalPoints() == 0.

Then we record the values of totalPoints and pointsOf[address] before and after the addPoints() method call. Doing so allows us to compute the deltas caused by the call and determine how much each variable has changed.

Lastly, we assert that the total points (totalPointsAfter) equal the initial total points (totalPointsBefore) plus the sum of changes in the points of account1 and account2. This adjustment makes the rule work regardless of the initial state:

rule sumOfUserPointsEqualsTotalPoints_modified() {

address account1; address account2;

uint256 amount1; uint256 amount2;

require account1 != account2;

// Capture the state BEFORE the method call

mathint totalPointsBefore = totalPoints();

mathint pointsOfAccount1Before = pointsOf(account1);

mathint pointsOfAccount2Before = pointsOf(account2);

// Method call

addPoints(account1, amount1);

addPoints(account2, amount2);

// Capture the state AFTER the method call

mathint totalPointsAfter = totalPoints();

mathint pointsOfAccount1After = pointsOf(account1);

mathint pointsOfAccount2After = pointsOf(account2);

// Calculate how much each account's points changed

mathint deltaPointsOfAccount1 = pointsOfAccount1After - pointsOfAccount1Before;

mathint deltaPointsOfAccount2 = pointsOfAccount2After - pointsOfAccount2Before;

// Assertion: The total points equal the initial total plus the changes in the points of account1 and account2

assert totalPointsAfter == totalPointsBefore + deltaPointsOfAccount1 + deltaPointsOfAccount2;

}

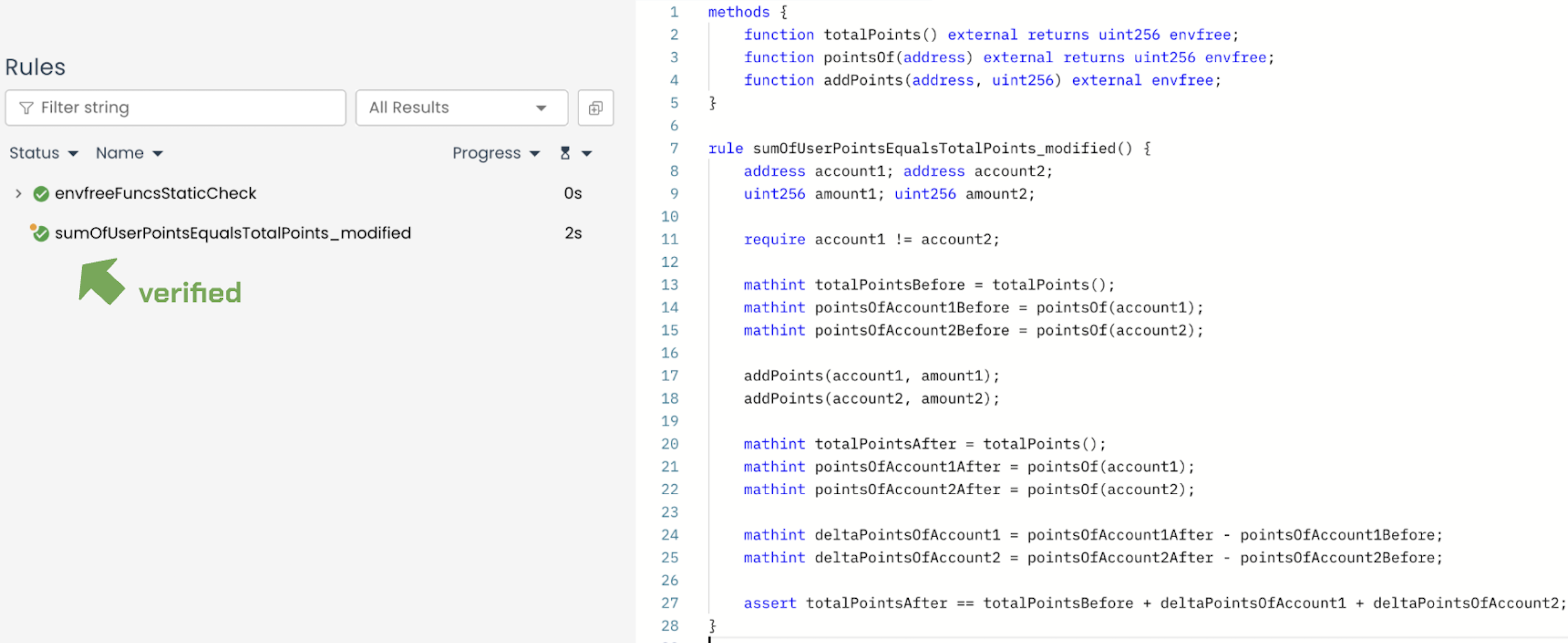

Prover run: link

Even with this rule improvement, it does not accurately represent the property, since it only considers two specific users and ignores all others in the mapping. It only proves that a subset of users is consistent with the total.

Tracking all user points is impossible without an Sstore hook, even if the mapping is externally accessible.

Using Sstore hook to enumerate storage mapping values

Every time the contract writes to pointsOf[address], the Sstore hook captures the new value and the old value, which allows it to calculate the delta (change) and assign it to a ghost variable. Instead of querying the mapping directly (from the contract) for all possible keys, we maintain a ghost variable tracker that records each storage write as it happens.

Let’s implement the Sstore hook logic. As mentioned, we capture the old and new values, calculate the delta (change) and add it to a ghost variable to record the total points. We declare this ghost variable as g_sumOfUserPoints:

ghost mathint g_sumOfUserPoints;

hook Sstore pointsOf[KEY address account] uint256 newVal (uint256 oldVal) {

g_sumOfUserPoints = g_sumOfUserPoints + newVal - oldVal;

}

Now that the sum of individual user points is quantifiable in the ghost variable g_sumOfUserPoints, the next step is to use it in a rule or an invariant to check that this tracker always equals the contract’s storage variable totalPoints.

Ghosts within rules and invariants

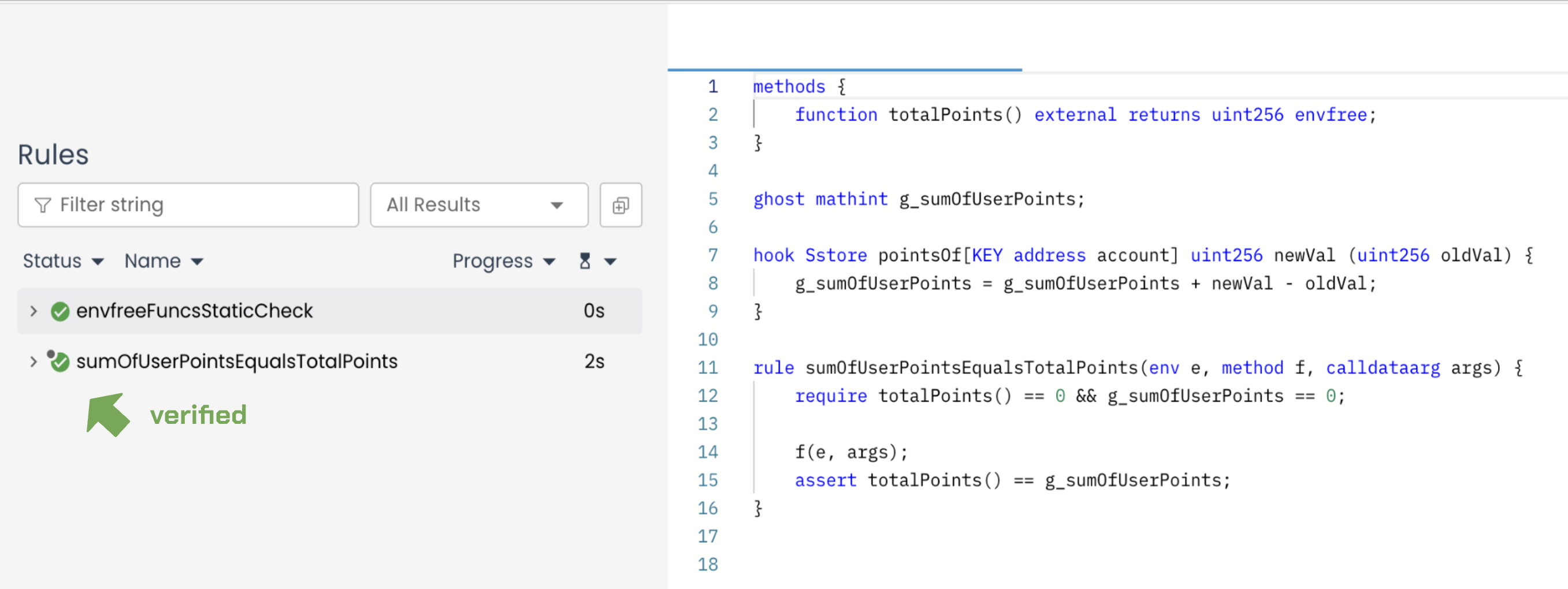

Ghosts can be used in both rules and invariants. In the following example, we verify that totalPoints (storage variable) equals g_sumOfUserPoints (ghost variable), whose value is tracked and calculated in the Sstore hook.

Verify totalPoints() equals g_sumOfUserPoints as a rule

Here’s the rule in parametric form, where f(e, args) allows the Prover to verify the rule against all contract functions with arbitrary arguments. For the rule below, we require totalPoints and g_sumOfUserPoints start at zero:

rule sumOfUserPointsEqualsTotalPoints(env e, method f, calldataarg args) {

require totalPoints() == 0 && g_sumOfUserPoints == 0;

f(e, args);

assert totalPoints() == g_sumOfUserPoints;

}

Prover run: link

Alternatively, we can allow totalPoints and g_sumOfUserPoints to start at any value, as long as they start at the same value:

rule sumOfUserPointsEqualsTotalPoints_alt(env e, method f, calldataarg args) {

require totalPoints() == g_sumOfUserPoints; // starts at any value, as long as they start at the same value

f(e, args);

assert totalPoints() == g_sumOfUserPoints;

}

Prover run (verified): link

Verify totalPoints() equals g_sumOfUserPoints as an invariant

To verify the same property inductively (base case and induction step), we write it as a CVL invariant. The ghost is initialized to zero, and the same Sstore hook from the previous rule is applied here:

ghost mathint g_sumOfUserPoints {

init_state axiom g_sumOfUserPoints == 0;

}

hook Sstore pointsOf[KEY address account] uint256 newVal (uint256 oldVal) {

g_sumOfUserPoints = g_sumOfUserPoints + newVal - oldVal;

}

invariant sumOfUserPointsEqualsTotalPoints_inv()

totalPoints() == g_sumOfUserPoints;

Prover run (verified): link

When using ghosts in a CVL invariant, it is necessary to initialize them with an init_state axiom that sets the correct starting value — in this case, zero for g_sumOfUserPoints.

Since each user’s points start at zero, the sum of all user points (g_sumOfUserPoints) also starts at zero. This matters because, as part of the induction process, an invariant checks whether the property holds in the base case (immediately after the constructor).

When we verified this property as a rule earlier, we tested the case where both started at zero and then at a non-zero (but equal) value. As an invariant, we only test both starting at zero.

The reason is that invariants must begin testing immediately after the constructor (the base case), where uninitialized storage variables are zero by default. This means invariants can only start at non-zero values if the constructor explicitly sets those values. Rules, however, can assume any arbitrary starting state — it can be zero or non-zero.

Summary

- Using an

Sstorehook is unavoidable for mappings when proving properties that involve changing values. It solves the enumeration problem by monitoring storage slots and capturing old and new values for mapping keys. - Without an

Sstorehook, properties can only be proven for a limited set of manually queried keys, rather than monitoring storage directly. - In rules, the initial values of ghost variables are constrained using

requirestatements. - In invariants, ghost variables are initialized using the

init_stateaxiom.