It often becomes necessary to inspect changes at specific storage locations to prove that a property or invariant holds, especially when the storage is not externally accessible or when the values of interest are not explicitly calculated or exposed by the contract.

For example, suppose we want to verify that, in an ERC-20 implementation, the value of totalSupply always equals the sum of all individual account balances. At first glance, this seems straightforward: we could assert totalSupply() == sumOfBalances().

However, the difficulty is that the contract never actually maintains this cumulative sum; it only stores each account’s balance in a mapping. Unlike totalSupply, which is stored explicitly and can be queried directly, the “sum of balances” does not exist in the contract’s state. Instead, this information is distributed across multiple storage slots, making it impossible to verify the relationship without observing how those slots are accessed and updated. The challenge becomes even greater when some of these variables are private.

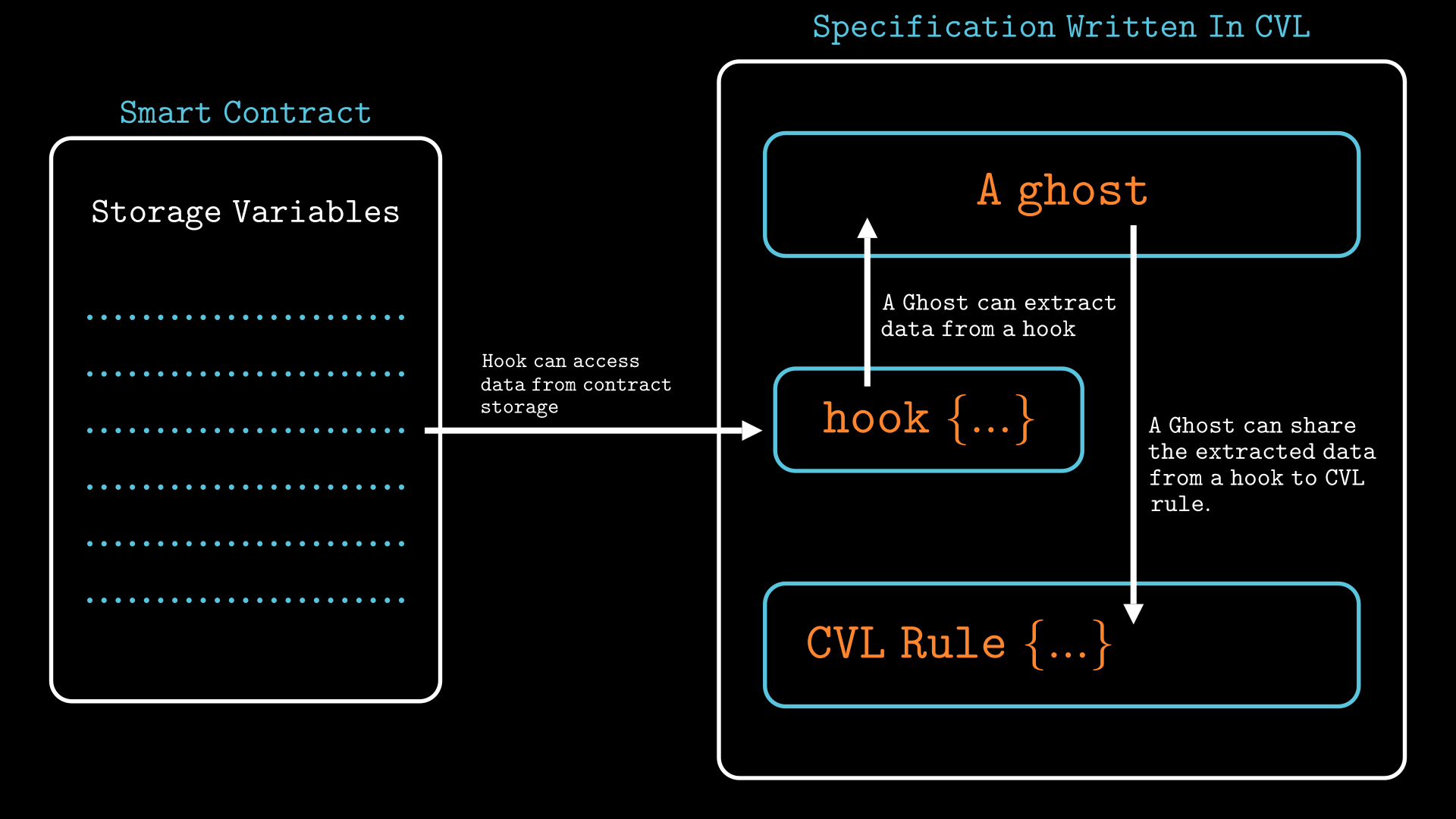

To address this challenge, CVL provides hooks and ghost variables. Hooks let us observe low-level events such as reads and writes to storage, while ghost variables let us capture, aggregate, and share those observations so they can be referenced elsewhere in the specification. Together, they bridge the gap between internal contract behavior and high-level verification rules, allowing us to reason about properties that depend on hidden or implicit state changes.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how hooks work, the different types available, and the limitations associated with them. We will also introduce you to ghost variables, a core CVL feature that enables communication between hooks and rules, enabling you to verify rich correctness properties that are otherwise hidden in the contract’s internal storage.

Understanding “the Need”

To better understand the problems we are talking about, consider the smart contract below that keeps a private count and an owner set at deployment. Both increment() and resetCounter() are protected by the onlyOwner modifier: increment() increments the private count by one and resetCounter() resets it to zero, and only the owner address stored in the contract can call either function.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Counter {

// State variables

address private owner;

uint256 private count;

/// @notice Initializes the contract and sets the deployer as the owner

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

}

/// @notice Restricts function calls to the contract owner only

modifier onlyOwner() {

require(msg.sender == owner, "Counter: caller is not the owner");

_;

}

// External functions

/// @notice Increments the counter by 1

/// @dev Only callable by the owner

function increment() external onlyOwner {

count++;

}

/// @notice Resets the counter to 0

/// @dev Only callable by the owner

function resetCounter() external onlyOwner {

count = 0;

}

}

Now suppose we want to formally verify the following properties:

- The

ownermust never change once it is set in the constructor. - A call to

increment()should increase thecountby exactly one.

At first glance, both properties look straightforward. However, expressing them in the form of CVL rules poses some challenges. The problem with expressing the first property as a CVL rule is that the owner variable is marked private, and the contract does not provide a getter to expose its value. Without being able to access it from a rule, we cannot assert that it remains unchanged once set in the constructor.

The second property introduces a different challenge. Although we can call increment() inside a rule, the variable count is private, and the contract provides no getter to read its value. This means the rule cannot directly see what happens to count when the function runs.

Since rules can only observe function inputs and outputs, not changes to internal storage, they have no way to capture the old and new values of count when it is updated. Without that visibility, the Prover cannot confirm that each call to increment() actually increases the counter by one.

Put simply, the problem is not that the properties are hard to state but that they depend on low-level storage behavior and require direct observation of how storage is updated during execution. Standard CVL rules are limited to interacting with the contract through its public interface, so they cannot capture these internal changes. To verify properties like immutability of the owner or exact increments of the counter, we need tools that allow us to peek inside the contract, monitor its storage operations, and carry those observations into our specifications.

This is where hooks come into play.

What Are Hooks?

In CVL, hooks are blocks of code that run automatically during the verification process whenever a smart contract performs low-level EVM operations, such as reading from or writing to storage, executing an opcode, or modifying transient data.

A hook is defined using the hook keyword, and each CVL hook specifies the following:

- The operation it listens for (for example, SLOAD, SSTORE, or a specific EVM opcode).

- A block of CVL code that executes when that operation is detected, providing access to relevant data from that event.

Types Of Hooks

CVL provides 3 different types of hooks, categorized by the kind of operation they monitor. Those 3 types are:

- Storage Hooks

- Opcode Hooks

- Transient Storage Hooks

For this specific chapter, we will focus on Storage Hooks, as they are the most widely applicable and form the foundation for understanding how hooks work in CVL. The other types of hooks are equally useful in specific contexts, and we will cover them in later chapters.

What are Storage Hooks?

Storage hooks are a specific type of hook in CVL that are triggered whenever a contract’s storage variable is accessed, whether for reading or writing. In other words, they activate when the EVM performs a read (SLOAD) or write (SSTORE) operation on a monitored storage slot, allowing us to:

- Capture the value being read or written.

- Enforce conditions whenever a variable is accessed or modified.

- Track how the contract’s state evolves across different executions.

There are two main kinds of storage hooks in CVL:

- The Load Hooks

- The Store Hooks

1. The Load Hooks

A load hook is triggered when a read operation (SLOAD) occurs on a monitored storage variable and allows you to capture the value being read.

It’s defined using the hook Sload keywords, followed by the type and a name for a CVL variable that will hold the loaded value, and finally, the name of the contract’s storage variable being monitored.

hook Sload address contractOwner owner { ... }

The above hook will be executed whenever the contract under verification accesses its owner storage variable, of type address, for a read operation. The value will then be stored in contractOwner, a CVL variable.

2. The Store Hooks

The store hooks are executed before any write operation takes place at any specific storage variable.

Store hooks are also defined using the hook keyword, followed by the Sstore keyword. After that, you specify the name of the contract’s storage variable being monitored, along with the type and name of the CVL variable that will hold the value about to be written to that storage location.

hook Sstore owner address newOwner{...}

Optionally, the pattern may also include the type and name of a variable to store the previous value that is being overwritten.

hook Sstore owner address newOwner (address oldOwner) {...}

Before we apply hooks to verify the properties of the Counter contract, there’s an important limitation to understand: variables declared inside hooks are local to the hook block and are not directly visible to rules.

Understanding the Limitations of Hooks

A hook not only allows us to monitor a specific storage variable but also provides access to its value by storing it in a CVL variable for use. However, one limitation is that CVL variables defined inside hooks are scoped locally to the hook, meaning they cannot be accessed directly from rules.

To understand this limitation, consider the specification below that aims to prove that the owner of the Counter contract never changes after it is first set in the constructor:

hook Sload address contractOwner owner {}

rule checkOwnerConsistency(env e) {

address prevOwner = contractOwner;

//parametric call

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e,args);

address currentOwner = contractOwner;

assert prevOwner == currentOwner;

}

In the above spec, the hook Sload makes the private owner variable observable whenever it is read, storing its value to contractOwner. In the rule, the spec saves this observed value as prevOwner, performs a symbolic call to any contract function with arbitrary inputs, then observes owner again as currentOwner. Finally, it asserts that prevOwner == currentOwner, meaning that across all possible calls, the owner must remain consistent.

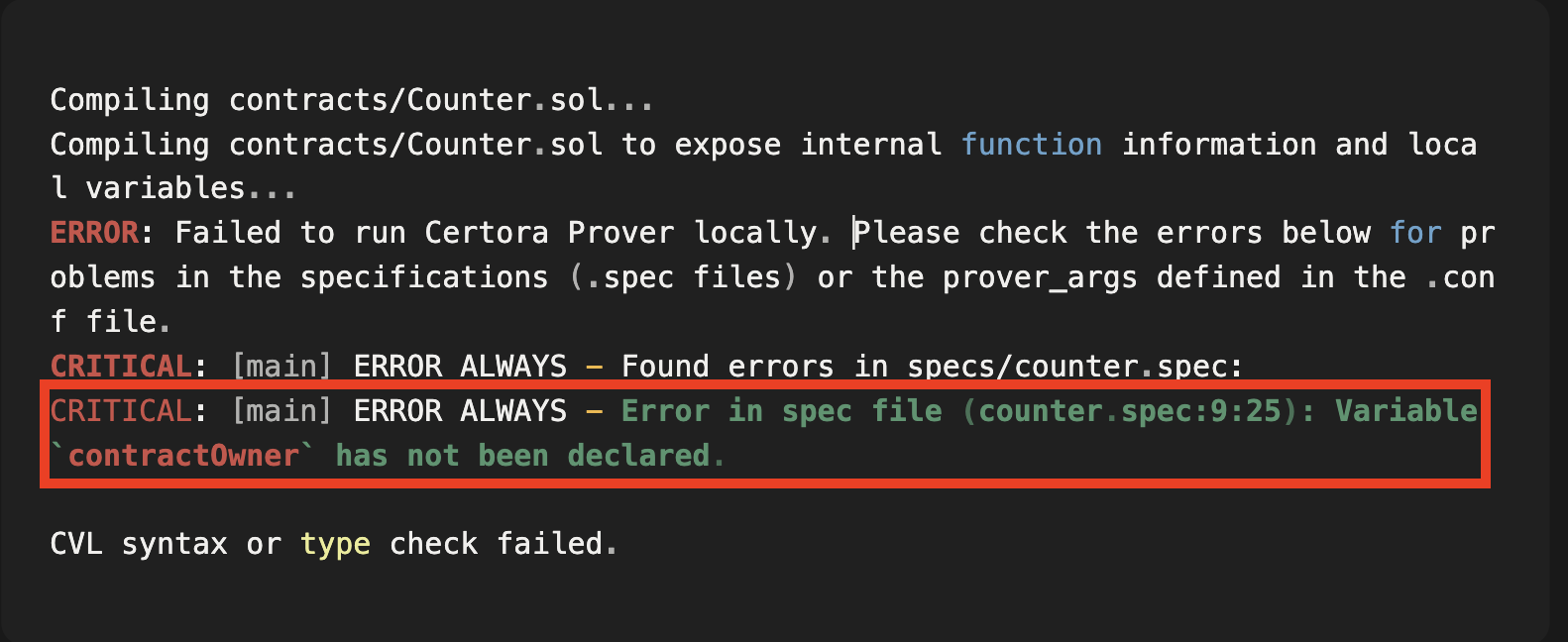

However, when you run the Certora Prover, you will experience the following error:

The above error simply highlights the fact that the rule checkOwnerConsistency() cannot access and use contractOwner declared inside our load hook.

This might raise the question: if hooks are designed to capture and store data, why can’t we use that data in our rules directly?

The answer lies in the scope of variables defined within hooks.

The Scope Limitation of Hooks

When you define a variable inside a hook, its scope is local to that hook only. It’s like defining a variable inside a function—it can be used within that block but is not visible outside. That’s why contractOwner is perfectly valid inside the hook, but completely unknown to the rule checkOwnerConsistency().

This means that CVL rules and hooks do not share variables—they operate in separate scopes.

So how can we use the information extracted in a hook to write useful rules?

The answer is ghost variables.

Working Around the Scope Limitation with Ghost

Although we can’t directly access hook variables inside rules, we can define special variables called ghost variables (or simply ghosts) to communicate information between hooks and rules.

A ghost is declared using the ghost keyword followed by its type and name, as shown below.

ghost bool hasVoted;

ghost uint x;

ghost mathint numVoted;

ghost mapping(address => mathint) balances;

A ghost variable can be any CVL supported type or a mapping. In the case of a mapping, its keys must be CVL supported types, and its values can be either CVL types or other mappings.

Verifying Owner Consistency in the Counter Contract

To make the checkOwnerConsistency() rule work as intended, the value observed inside the hook needs to be made available in the rule’s scope. We can accomplish this by storing the observed value in a ghost variable. The steps to achieve this are outlined below:

1. Declare a ghost to hold the observed value of owner: At the top level of our specification, introduce a ghost variable called ghostOwner. This ghost will serve as a container for the value of the contract’s owner slot whenever it is read.

/// Top-level ghost variable to mirror the contract's `owner` slot

ghost address ghostOwner;

hook Sload address contractOwner owner {}

rule checkOwnerConsistency(env e) {

address prevOwner = contractOwner;

//parametric call

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e,args);

address currentOwner = contractOwner;

assert prevOwner == currentOwner;

}

When declaring ghost variables, it is important to prefix them with ghost or ghost_ (for example, ghostOwner, ghost_owner) to clearly distinguish them from Solidity storage variables and hook-local CVL variables.

At this stage, the ghost variable ghostOwner has been declared but is not yet synchronized with the contract’s storage.

2. Synchronize the ghost inside the hook: Next,modify the Sload hook so that whenever the contract performs a read on the owner storage slot, the hook captures the value and writes it into the ghost.

ghost address ghostOwner;

hook Sload address contractOwner owner {

//assign captured value to ghost

ghostOwner = contractOwner;

}

rule checkOwnerConsistency(env e) {

address prevOwner = contractOwner;

//parametric call

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e,args);

address currentOwner = contractOwner;

assert prevOwner == currentOwner;

}

This creates a bridge from the contract’s private storage into the hook, and from the hook into a ghost variable that persists beyond the hook’s local scope. Every time the contract reads owner, the ghost ghostOwner is synchronized with that storage value.

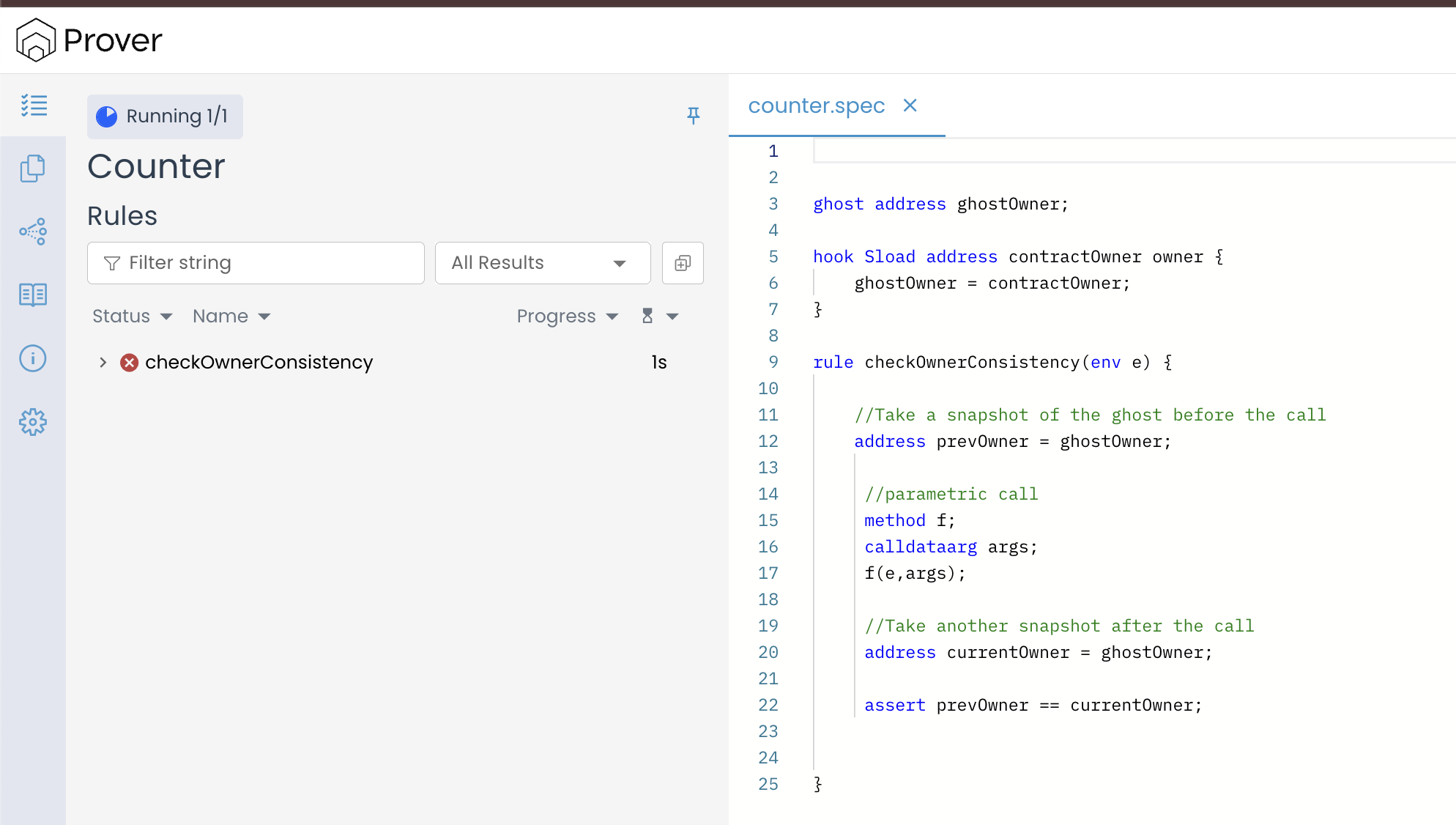

3. Use the ghost inside the rule: Finally, update the checkOwnerConsistency() rule so that instead of using the hook-local contractOwner, it references the ghost ghostOwner.

ghost address ghostOwner;

hook Sload address contractOwner owner {

ghostOwner = contractOwner;

}

rule checkOwnerConsistency(env e) {

//Take a snapshot of the ghost before the call

address prevOwner = ghostOwner;

//parametric call

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e,args);

//Take another snapshot after the call

address currentOwner = ghostOwner;

assert prevOwner == currentOwner;

}

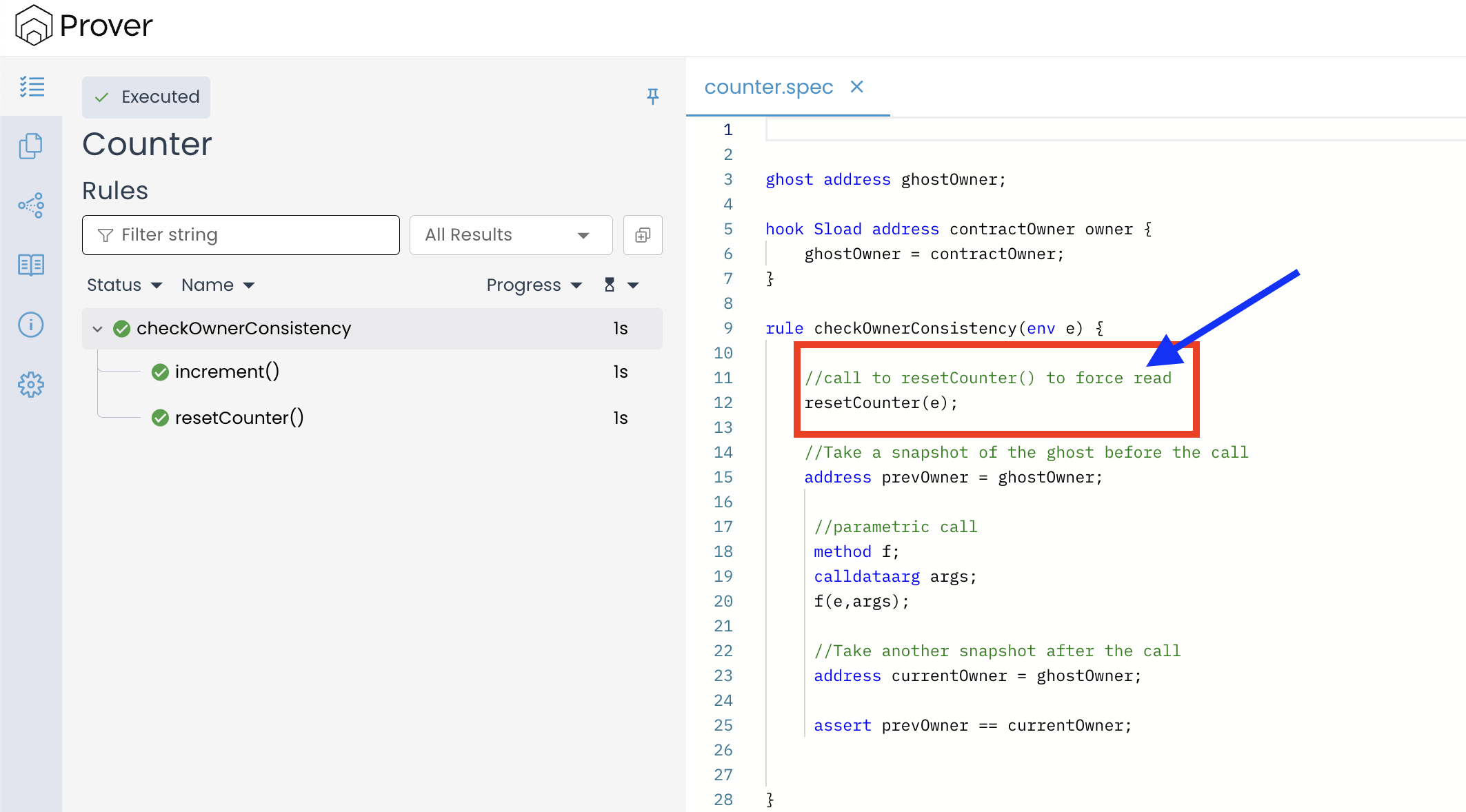

Once you’ve updated your specification as per the instructions provided above, re-run the Certora Prover using the certoraRun command. This time the Prover will compile our rule without any error and will print out the verification result in your terminal. The result will be similar to the image below:

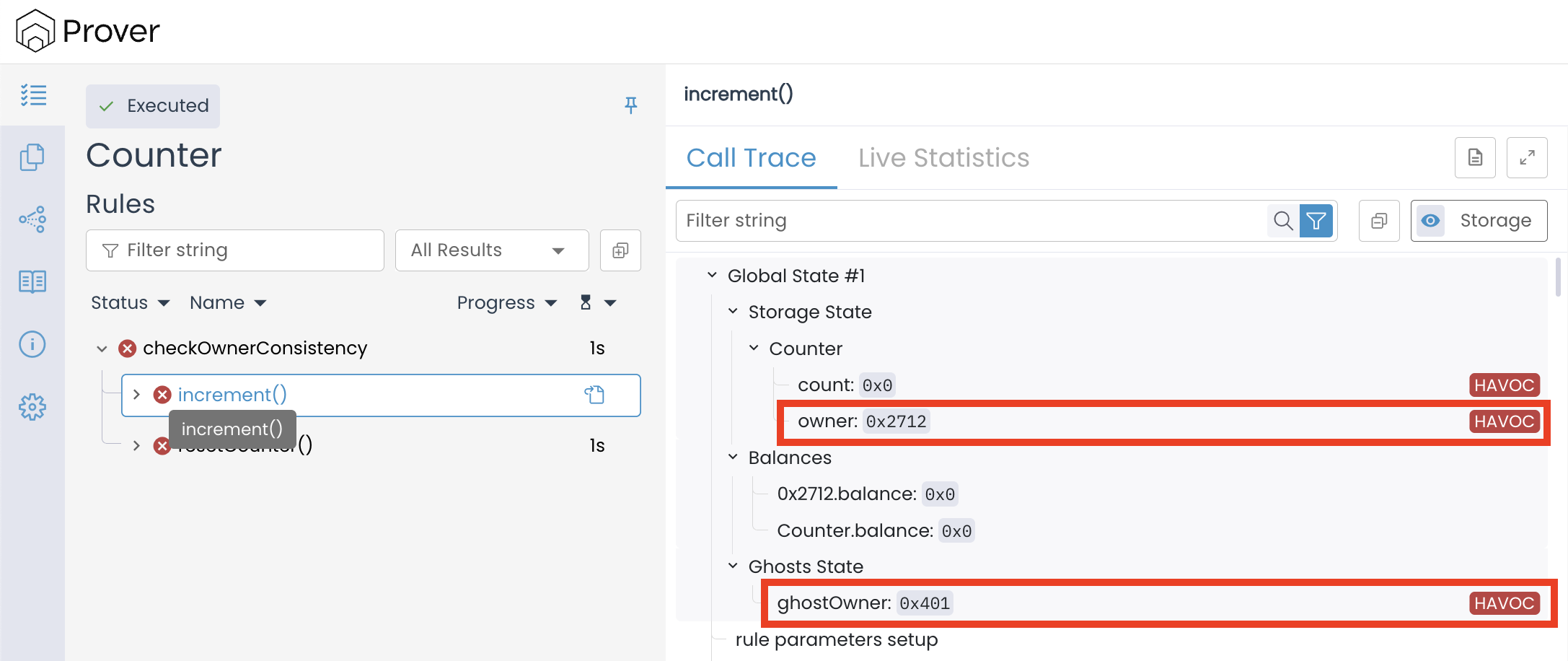

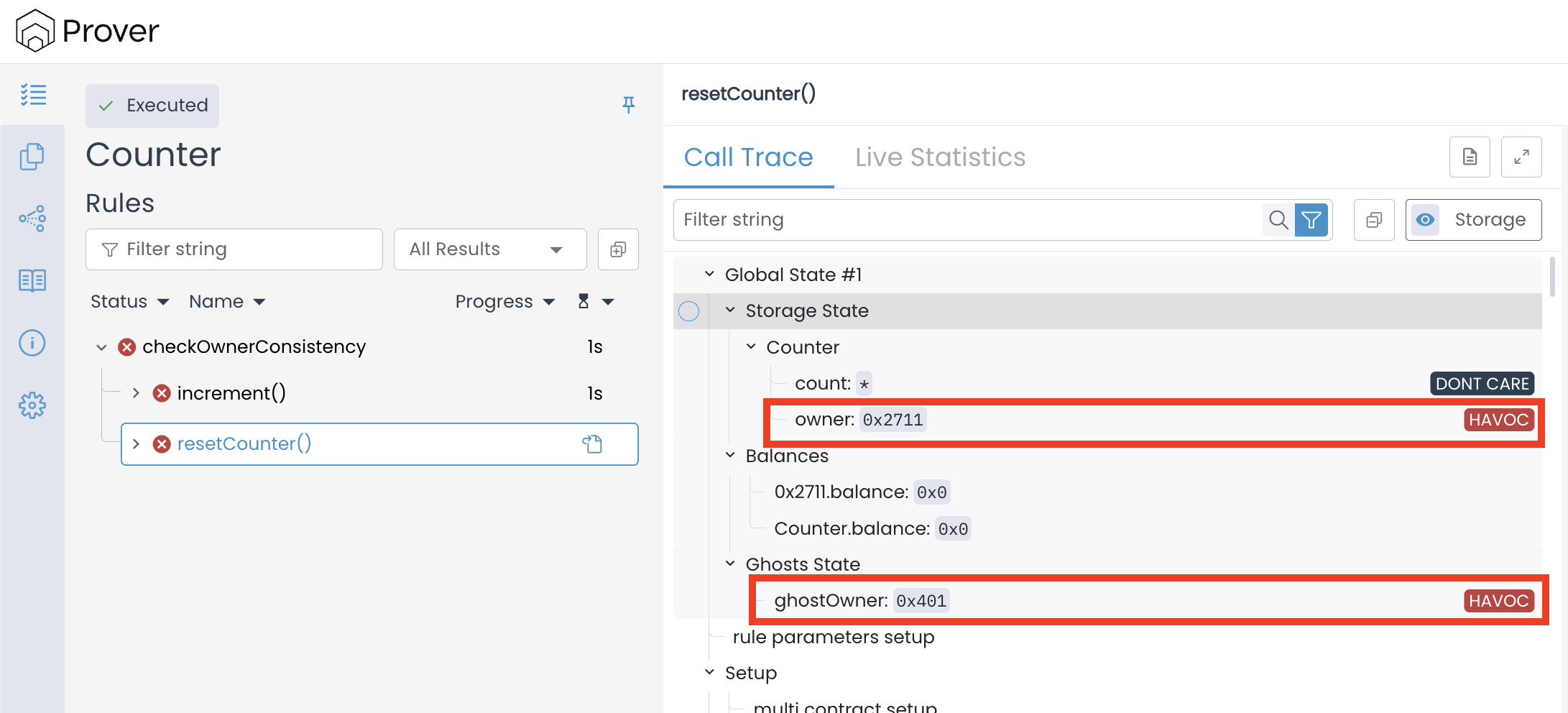

After seeing the result above, you might be surprised and wonder why our rule still failed even though the Counter contract never explicitly updates its owner. The reason lies not in the Solidity code but in how the Prover interprets ghosts and how the hooks are executed during verification run.

Synchronizing Ghosts with Storage

Ghost variables are not automatically tied to the contract’s storage. At the start of execution, the Prover assigns them havoced values — arbitrary placeholders that can change across traces unless they are explicitly initialised. In our case, the ghost ghostOwner is only updated when the owner slot is read (via Sload). If no read occurs before the rule compares prevOwner and currentOwner, the ghost remains uninitialised, holding an arbitrary value unrelated to the actual storage.

This is what actually happened: the storage slot for owner held one address (e.g., 0x2712 or 0x2711), but the ghost ghostOwner contained a completely different value (e.g.,0x401).

Since the ghost was never aligned with storage, our rule ended up comparing two meaningless values, and the Prover quite correctly reported a failure.

We can see that the main issue is that ghost variables do not automatically mirror contract storage. To fix this, we need to make sure that the ghost is explicitly updated through a hook before it is used in a rule. In practice, this means forcing the contract to perform a read of the relevant storage slot so the Sload hook can trigger and synchronize the ghost with the actual value in storage.

To achieve this, we simply make an initial call that causes the contract to read the owner slot, which in turn fires the Sload hook and updates our ghost. In our case, we will do this by calling resetCounter(e) at the start of the rule. Because resetCounter(e) is protected by the onlyOwner modifier, the EVM must read the owner storage slot to check the modifier’s condition. This read automatically fires the hook, ensuring that ghostOwner is updated before we capture it into prevOwner.

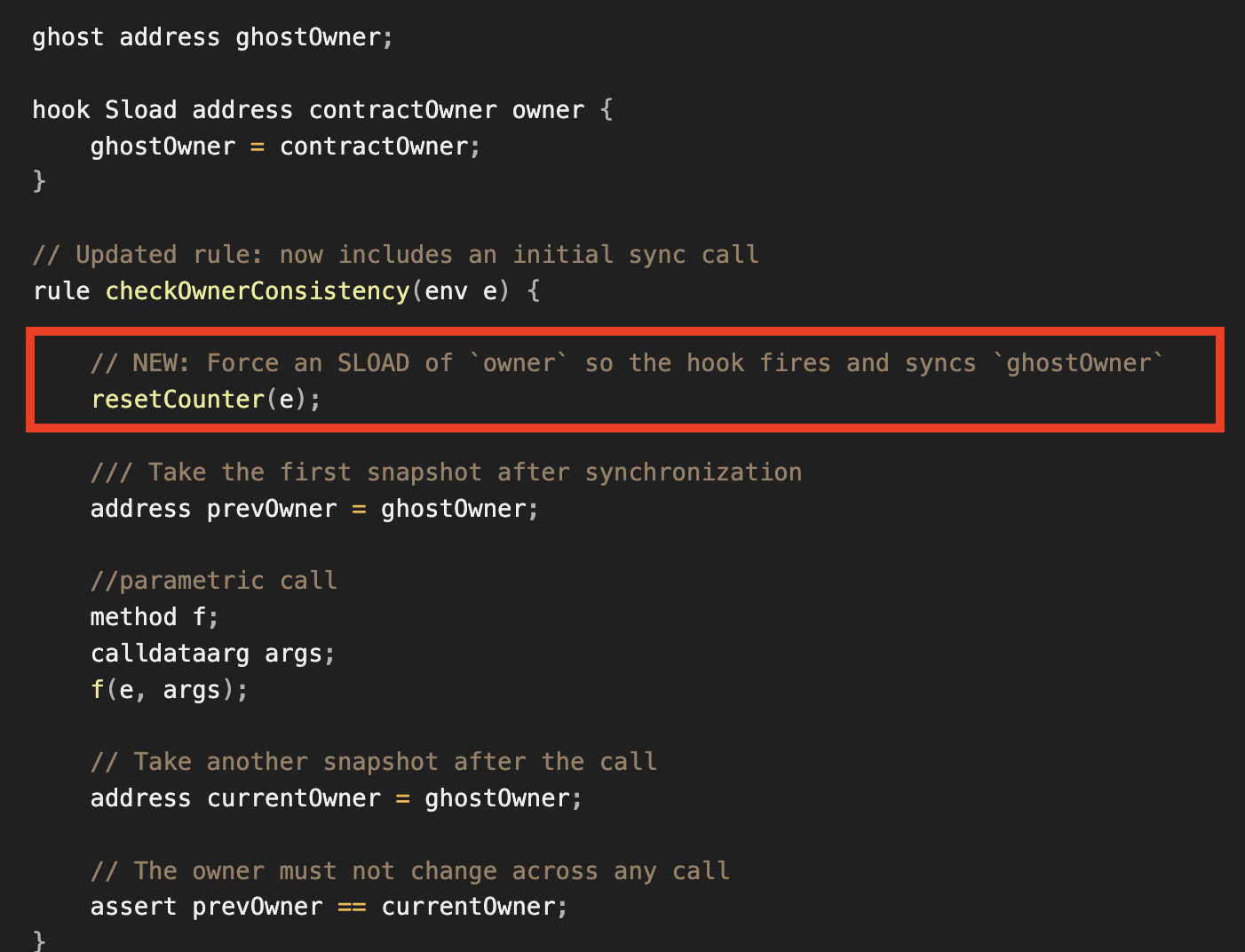

Below is the updated specification showing the modified rule in full:

ghost address ghostOwner;

hook Sload address contractOwner owner {

ghostOwner = contractOwner;

}

// Updated rule: now includes an initial sync call

rule checkOwnerConsistency(env e) {

// NEW: Force an SLOAD of `owner` so the hook fires and syncs `ghostOwner`

resetCounter(e);

/// Take the first snapshot after synchronization

address prevOwner = ghostOwner;

//parametric call

method f;

calldataarg args;

f(e, args);

// Take another snapshot after the call

address currentOwner = ghostOwner;

// The owner must not change across any call

assert prevOwner == currentOwner;

}

The first line inside the rule (resetCounter(e);) is the key addition.

With the ghost now properly synchronized, the comparison between prevOwner and currentOwner becomes meaningful, allowing the Prover to correctly verify the consistency of the owner variable.

Let’s break down what happened here, step by step:

- Initial sync call (

resetCounter(e))- The rule begins by calling

resetCounter(e). - To check the

onlyOwnermodifier, the contract must read theownerslot (SLOAD). - That read fires the

Sloadhook, which writes the observed value into the ghostghostOwner. - As a result,

ghostOwneris now synchronized with the actual storage value before we take any snapshot.

- The rule begins by calling

- First snapshot (

prevOwner)- Right after the sync, the rule executes

address prevOwner = ghostOwner;. - Because of Step 1,

prevOwneris the real owner as stored in the contract.

- Right after the sync, the rule executes

- Arbitrary call (

method f; calldataarg args; f(e, args);)- The Prover now explores an arbitrary external call with symbolic inputs.

- In this contract, that means either

increment(...)orresetCounter(...)with arbitrary arguements. - Both functions are guarded by

onlyOwnerand do not write to owner. - During this call, any additional reads of

owner(because ofonlyOwner) will re-fire theSloadhook, but it will just write the same value into the ghost.

- Second snapshot (

currentOwner)- After the arbitrary call returns, the rule executes

address currentOwner = ghostOwner;. - Since the contract never mutates

owner, and the hook only mirrors reads,currentOwnerequals the same storage-backed value captured earlier.

- After the arbitrary call returns, the rule executes

- Assertion

- The rule checks

assert prevOwner == currentOwner;. - Since the contract never modifies

ownerafter deployment, there is no code path where these two snapshots can differ. - Hence, across all explored executions,

prevOwnerandcurrentOwneralways remain equal. - As a result, the Prover finds no counterexample and reports the rule as verified.

- The rule checks

With the owner property verified, let’s now turn to the second property we identified earlier.

Verifying the Increment() Call in Counter Contract

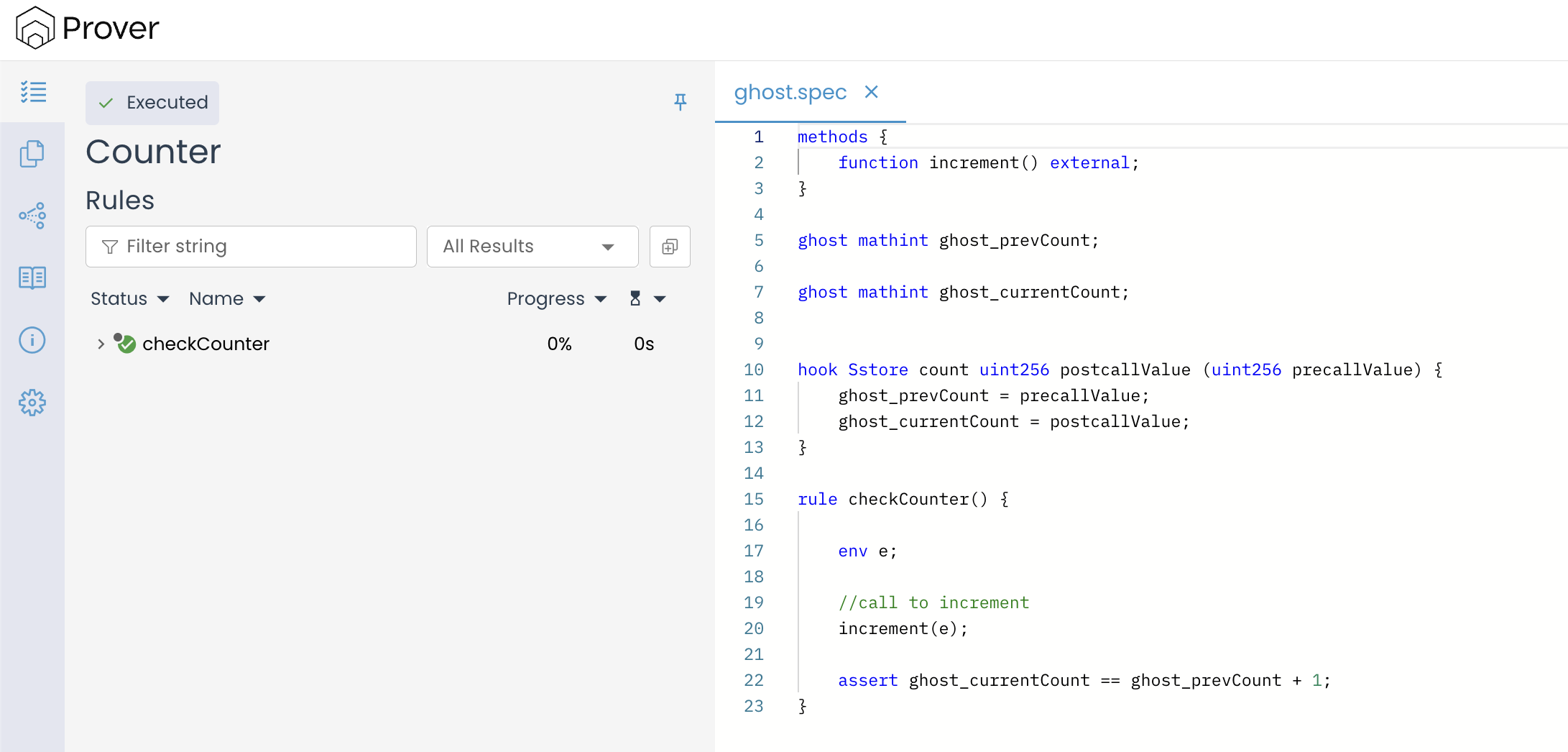

The second property we want to prove is that a call to increment() should increase the count by exactly one. Because count is private, rules alone cannot observe the actual storage write performed by count++. To prove this property, we attach a store hook to the count slot, capture the pre and post write values, persist them into ghosts, and finally assert the arithmetic relation in a rule.

Here is what the complete specification looks like:

methods {

function increment() external;

}

ghost mathint ghost_prevCount;

ghost mathint ghost_currentCount;

hook Sstore count uint256 postcallValue (uint256 precallValue) {

ghost_prevCount = precallValue;

ghost_currentCount = postcallValue;

}

rule checkCounter() {

env e;

//call to increment

increment(e);

assert ghost_currentCount == ghost_prevCount + 1;

}

In the spec above, the hook observes updates to the count storage slot whenever the increment() function is called. The old value (precallValue) is stored in one ghost variable (ghost_prevCount), while the new value (postcallValue) is stored in another (ghost_currentCount). This allows the rule to check whether the counter has increased exactly by one, as expected, after a call to the increment() function.

When we run the Prover on the spec above, we will see that the rule has been verified, as shown in the image below:

Let’s break down what happens here step by step:

- Before the call: The contract’s private variable

counthas some initial value (say X). - During the

increment()call:- The EVM executes the statement

count++, which translates into a read followed by a write on thecountstorage slot. - Just before the write occurs, the

Sstorehook is triggered. - The hook captures the value that was about to be overwritten (

precallValue) and the new value being written (postcallValue). - These are stored in the ghost variables

ghost_prevCountandghost_currentCount.

- The EVM executes the statement

- The rule check:

- After the function call completes, the rule asserts that

ghost_currentCount == ghost_prevCount + 1. - Given that

ghost_currentCount = X + 1andghost_prevCount = X, the assertion holds true.

- After the function call completes, the rule asserts that

Hence, we got a verified result from the Prover. In other words, any call to increment() increases the counter by exactly one, and the Prover was able to formally verify this property without finding any counterexample.

Ghost Variables as an Extension of Storage

We can see that hooks are used to observe and collect data by detecting specific read or write operations on the contract’s storage. However, since variables declared inside hooks are local to the hook, their values disappear once the hook finishes executing. To retain and reuse this information across the specification, CVL introduces ghost variables — persistent, specification-level storage that mirrors or extends the contract’s actual state. Because of this, ghost variables can be seen and treated as an extension of the contract’s storage.

In fact, the Certora Prover treats ghost variables much like regular storage:

- Any update to a ghost is reverted automatically if the transaction in progress later reverts, just like storage.

- At the start of a verification run, ghosts (as with other CVL variables) represent arbitrary (havoced) values unless they are explicitly set in the specification, reflecting the Prover’s symbolic view of storage.

We’ll explore these behaviours in greater detail in a later chapter, where we’ll also learn how to explicitly initialize ghost variables to avoid unintended havocing and ensure more predictable verification outcomes.

Conclusion

Certora hooks provide powerful observability into storage and EVM operations. However, their variables are limited to each hook’s local scope. Ghost variables solve this problem by capturing data from hooks and making it accessible to rules, thereby enabling effective and comprehensive reasoning about a contract’s internal state during the verification.