In this chapter, we will learn how to use method tags (@withrevert and @norevert) and the special variable lastReverted in CVL to verify expected reverts in smart contract execution.

Setting Up Verification Scenarios for the Add() function

Consider the following Math contract, which has a basic add() function that takes two unsigned integers as its inputs and returns their sum as its output.

//SPDX-License-Identifier : MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Math {

function add(uint256 x, uint256 y) public pure returns (uint256) {

return x + y;

}

}

The add() function behaves as follows:

- When provided with valid inputs, it should correctly calculate the sum of

xandy, and return the result as auint256value. For example,add(15, 10)will return 25. - Since the contract uses Solidity version 0.8.0 or later, the transaction will revert if the sum exceeds the maximum value of

uint256(2^256 - 1). For example, ifx = 2^256 - 1andy = 1, the overflow will cause the transaction to revert instead of returning a result.

Verifying the add() Function Specification

Consider the following specification to verify the correctness of the add() function from the Math contract:

methods {

function add(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

rule checkAdd() {

uint256 a;

uint256 b;

uint256 c = add(a,b);

assert a + b == c;

}

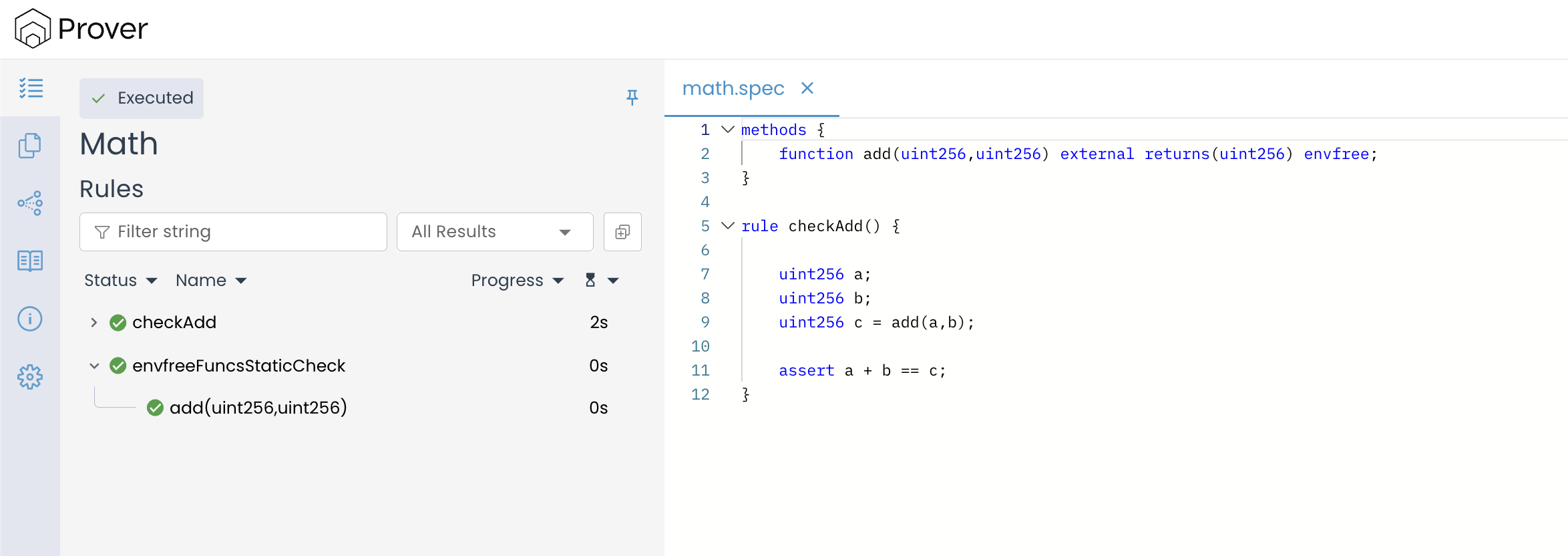

To view the verification result of the above spec, run the Prover and open the verification link to see a result similar to the image below.

This might seem surprising because the add() function is expected to revert when the sum of x and y exceeds the maximum uint256 value. Since the Prover explores different execution paths to verify correctness, one would expect it to encounter the revert scenario as well. In such cases, the assert statement should evaluate to false, and the rule should fail verification.

However, this did not happen, and our rule was still verified by the Prover. This is because, by default, the Prover ignores revert cases during verification.

This raises an important question: Why does the Prover choose to ignore revert cases during verification?

Why the Prover Ignores Reverts Path?

The reason is that reverts can be a normal part of operation—for example, if someone other than the contract owner tries to perform a privileged action. In such cases, a revert is not considered a failure; it is the expected behavior.

By ignoring revert paths, the Prover focuses on verifying successful execution scenarios where the function completes without errors. However, we can override this default behavior using the @withrevert method tag provided by CVL.

Introduction to CVL Method Tags

Certora provides us with two method tags, @norevert and @withrevert, which can be placed after the method name but before the method’s arguments, as shown below:

function_name@norevert();

function_name@withrevert();

When we use the @norevert tag with a method call, the Prover actively disregards any execution paths that result in a revert. In other words, function_name@norevert() behaves identically to function_name() .

On the other hand, when we use the @withrevert tag with a method call, the Prover no longer ignores revert cases. Instead, it treats any scenario where a revert occurs as a violation. For example, consider the checkAdd() rule below with the tag @withrevert:

methods {

function add(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

rule checkAdd() {

uint256 a;

uint256 b;

uint256 c = add@withrevert(a,b);

assert a + b == c;

}

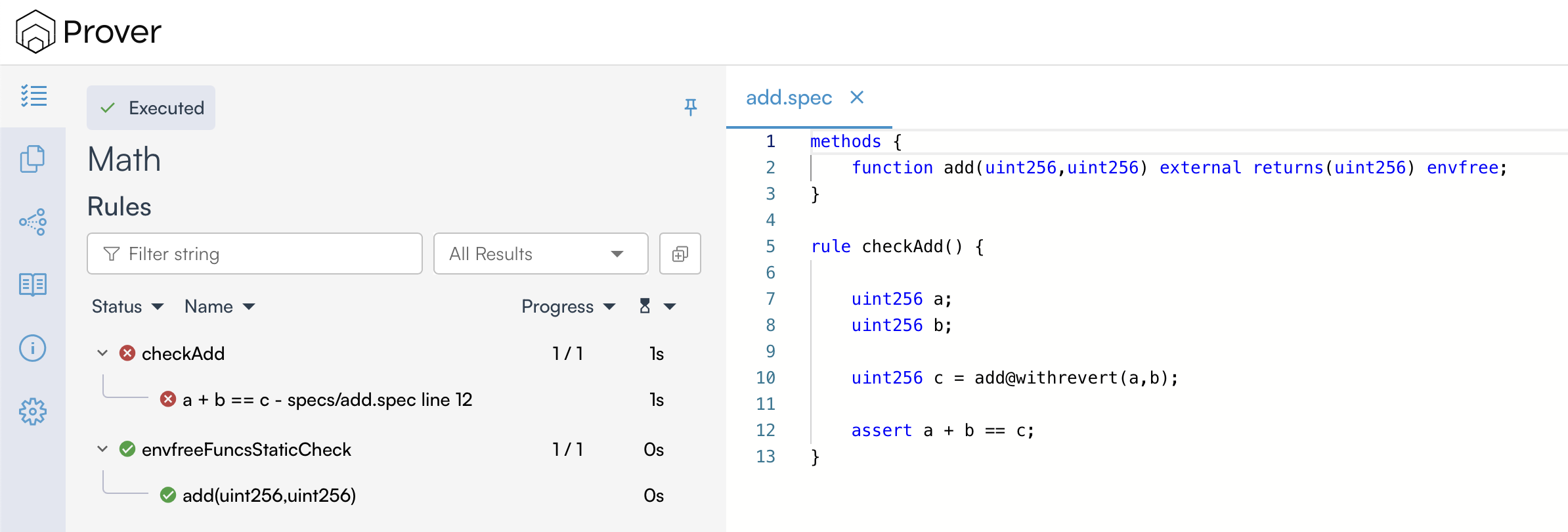

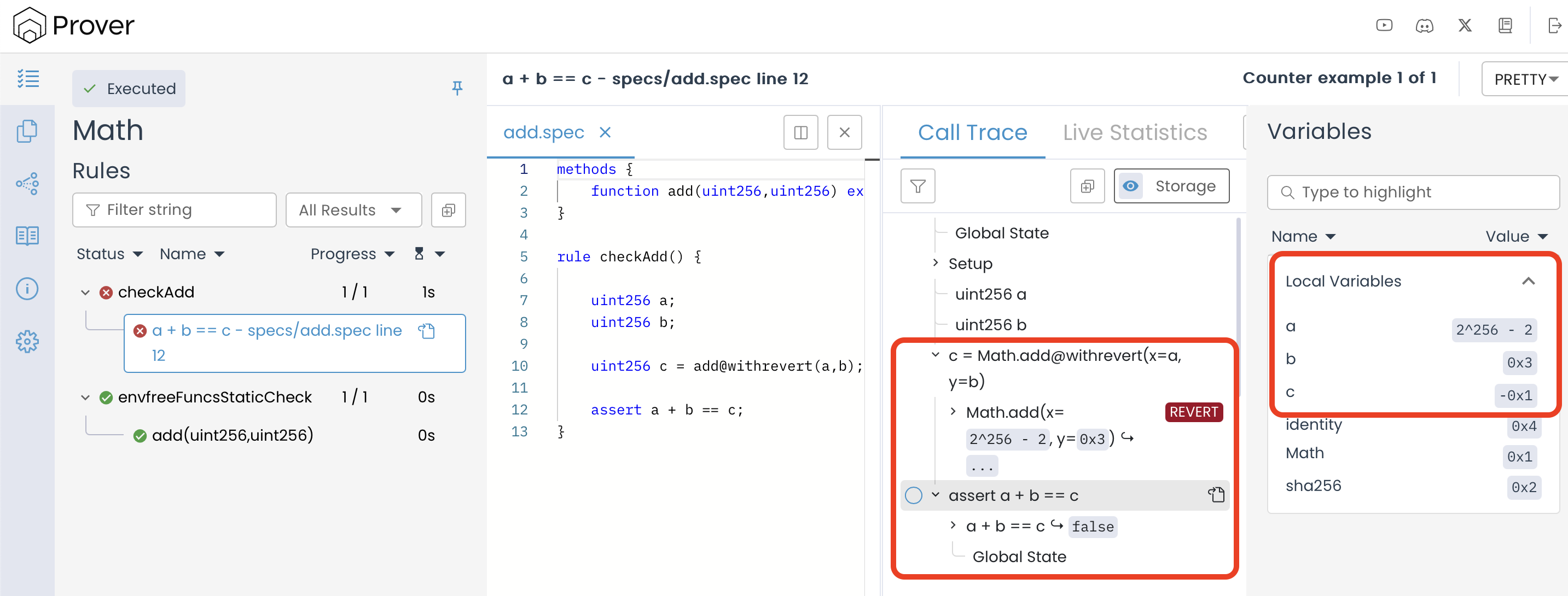

When we re-run the Prover with this updated specification, the outcome changes: the rule now fails verification, as shown in the image below:

Since we used the @withrevert tag with the add() function call, the Prover no longer ignores revert cases. As a result, if the sum of a and b exceeds the maximum uint256 value, the rule treats the revert as a violation. The verifier detects this issue and reports a counterexample—one that leads to an overflow and a revert, ultimately causing the assertion to fail. When a revert occurs, there’s no return value—c is unconstrained and can take an arbitrary value. Because of this, the assertion a + b == c cannot hold.

Introducing CVL Special Variable: lastReverted

In CVL, we have access to a special boolean variable called lastReverted, which is updated after each method call—including those made without @withrevert. This variable indicates whether the most recent contract function reverted (lastReverted = true) or executed successfully (lastReverted = false).

By default, however, the Prover ignores any execution paths that would result in a revert. This means that when a function is called without @withrevert—such as with the default call or using the @norevert tag—the Prover does not explore revert scenarios, and value of lastReverted will always remain set to false.

To accurately track whether a function reverts, we must explicitly instruct the Prover to consider revert paths using the @withrevert tag. When a function is called with @withrevert, the Prover no longer ignores revert scenarios, and if a revert occurs, lastReverted is updated to true.

Example: Detecting Reverts Due to Overflow

Now, let’s look at how lastReverted can be used in practical verification rules. We will test a function add(), ensuring it behaves correctly in cases where an overflow does and does not occur.

Case 1: Function Should Revert on Overflow

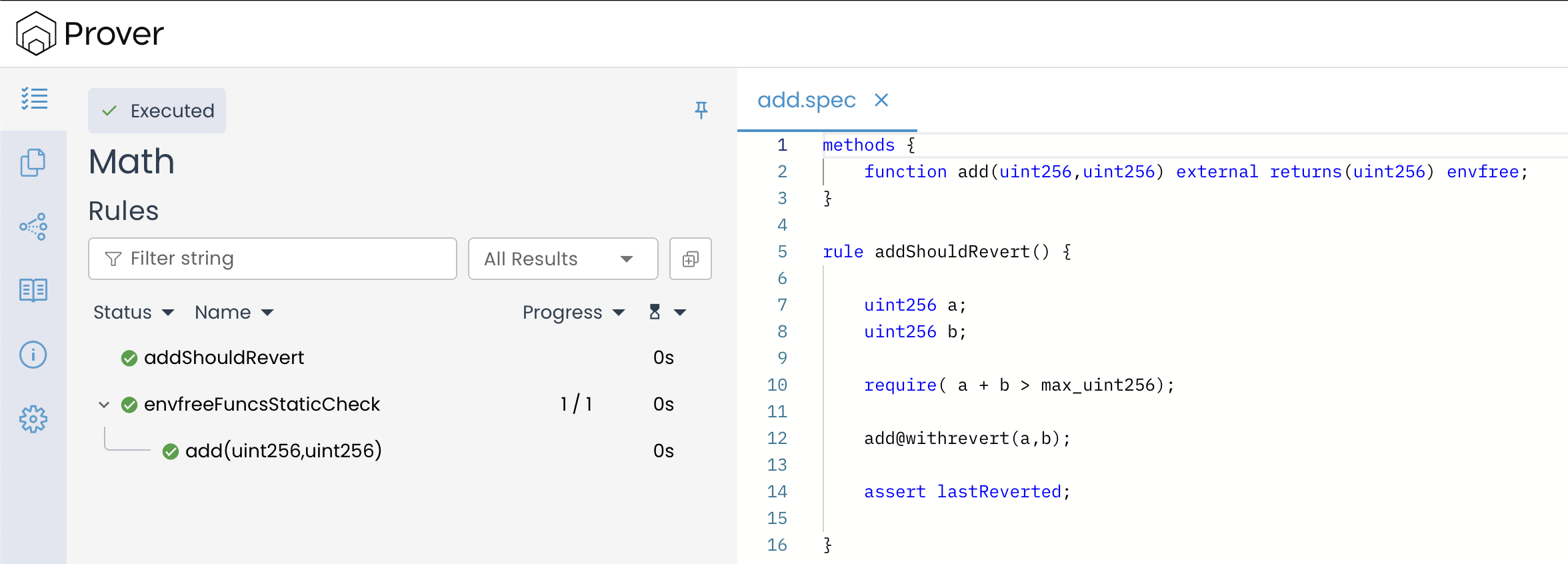

Consider the rule addShouldRevert() below, which aims to verify that the add() function correctly reverts when an overflow occurs.

methods {

function add(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

rule addShouldRevert() {

uint256 a;

uint256 b;

require(a + b > max_uint256);

add@withrevert(a,b);

assert lastReverted; // This is the same as assert lastReverted == true;

}

The statement require(a + b > max_uint256); in the addShouldRevert() rule ensures that the inputs a and b are chosen in such a way that their sum exceeds the maximum value a uint256 can store, causing an overflow. Solidity’s arithmetic operations automatically revert in cases of overflow, triggering a revert for the add(a, b) function call.

Note: In CVL, the maximum values for different integer types are available as variables, such as max_uint8, max_uint16, …, max_uint256, etc.

Because the function is invoked using @withrevert, the Prover does not ignore this revert scenario and correctly detects it. As a result, lastReverted is set to true, indicating that the function execution was reverted. The assertion assert lastReverted; then evaluates to true, as lastReverted matches the expected outcome. Consequently, the rule should pass, as shown in the image below.

Case 2: Function Should Not Revert on Valid Addition

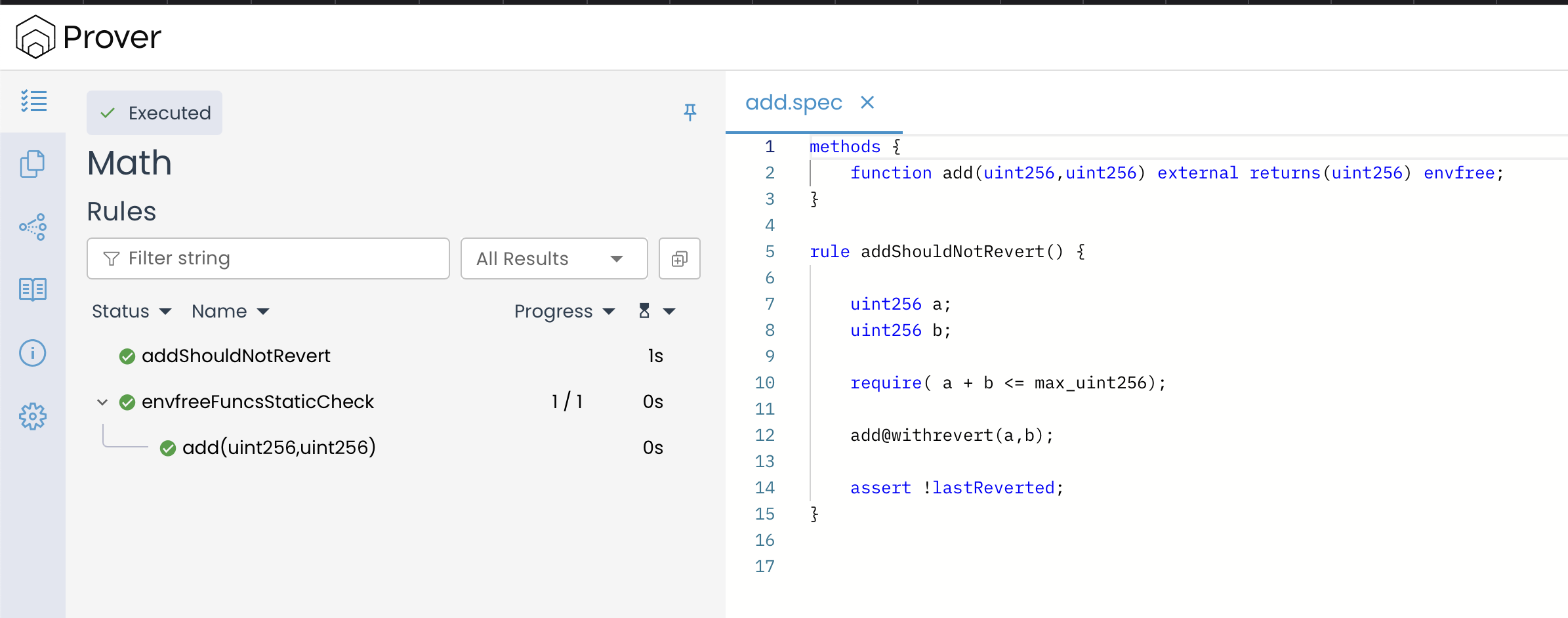

Similarly, consider the addShouldNotRevert() rule, which aims to verify that the add() function does not revert when the sum of a and b remains within the valid uint256 range.

methods {

function add(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

rule addShouldNotRevert() {

uint256 a;

uint256 b;

require(a + b <= max_uint256);

add@withrevert(a,b);

assert !lastReverted;

}

In the rule above, the statement require(a + b <= max_uint256); ensures that the inputs a and b are chosen in such a way that their sum does not cause an overflow. Since Solidity’s arithmetic operations only revert when an overflow or other explicit failure occurs, the add(a, b) function executes successfully without reverting.

Since the function is called with @withrevert, the Prover tracks whether a revert occurs. However, because the addition does not exceed the uint256 limit, no revert happens, and lastReverted remains false. The assertion assert !lastReverted; verifies this, ensuring that the rule passes successfully, as shown below.

Avoiding Overwriting of lastReverted

Since lastReverted updates after every function call, subsequent calls can overwrite its value. This means that if a function reverts but another function executes immediately afterward, the original revert status is lost.

To prevent verification errors, always capture lastReverted immediately after the relevant function call, before making additional calls that could overwrite its value.

To illustrate this, let’s consider a simple arithmetic contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

contract Math {

function add(uint256 x, uint256 y) public pure returns (uint256) {

return x + y;

}

function divide(uint256 x, uint256 y) public pure returns (uint256) {

return x / y;

}

}

The above contract defines two basic functions:

add(x, y)simply returns the sum ofxandy.divide(x, y)performs integer division, which reverts ify == 0due to Solidity’s built-in division by zero protection.

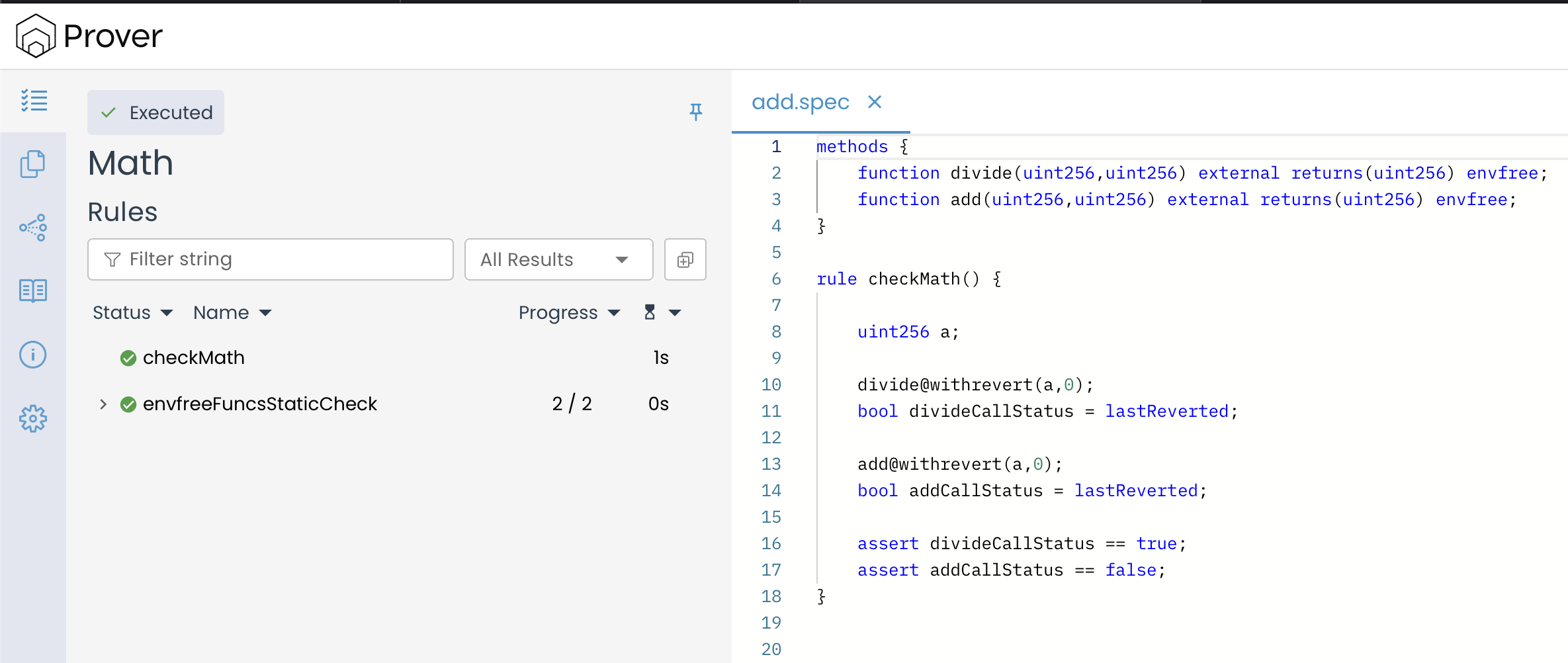

Now, consider the following rule designed to verify how both functions behave when receiving 0 as the second argument:

methods {

function divide(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

function add(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

rule checkMath() {

uint256 a;

divide@withrevert(a,0);

bool divideCallStatus = lastReverted;

add@withrevert(a,0);

bool addCallStatus = lastReverted;

assert divideCallStatus == true;

assert addCallStatus == false;

}

If we don’t store lastReverted immediately after calling divide(a, 0), the next function call (add(a, 0)) will update it again, completely erasing the information about the division operation failing.

This means that if a rule later checks whether divide(a, 0) reverted, it might incorrectly conclude that the function executed successfully—even though it actually failed. Such false verification can result in incorrect contract analysis, leading to security vulnerabilities or faulty assumptions in critical logic.

By storing lastReverted immediately after calling divide(a, 0), we ensure that we accurately capture the function’s behavior before making any other calls. This preserves the correct execution history, preventing unintended overwrites and ensuring reliable verification.

Wrapping Up

Testing both success and revert cases is crucial for performing formal verification of a method, as it provides better coverage and ensures that the method behaves correctly under all possible input conditions, including edge cases like overflows or invalid inputs.