Introduction

Some contract behaviors (properties) are inherently conditional, and using constructs like if/else in CVL is one way to capture conditional behavior formally.

if/else statements in CVL work the way they do in other languages. We’ll provide examples here of formally verifying code with conditional features.

Assertions And Method Invocations

Let’s start by formally verifying a simple function that takes two unsigned integers (uint256) and returns their sum (uint256). The expected outcome is conditional: if the addition overflows, the function reverts; otherwise, it returns the sum.

Below is the Solidity implementation of the add() function:

/// Solidity

function add(uint256 x, uint256 y) external pure returns (uint256) {

return x + y;

}

And here is the CVL specification (sum is a reserved keyword since P__rover version 7.25.2, so we use _sum instead.):

/// CVL

methods {

function add(uint256,uint256) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

rule add_sumWithOverflowRevert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint _sum = x + y;

if (_sum <= max_uint256) { // non-revert case

mathint result = add@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == _sum;

}

else { // revert case

add@withrevert(x, y);

assert lastReverted;

}

}

Let’s break down what’s happening in the specification code above. In the following lines,

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint _sum = x + y;

the variable _sum is declared as a mathint, a type without overflow limits, allowing it to accurately represent x + y even if it exceeds max_uint256. This enables us to detect overflow by comparing _sum to max_uint256 and determine whether the function should revert.

Now in the following lines,

if (_sum <= max_uint256) {

mathint result = add@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == _sum;

}

the Solidity addition operation is performed if _sum = x + y remains within the bounds of max_uint256.

The @withrevert tag is added to a function to instruct the Prover to include reverting paths or arguments that cause a revert. The assert !lastReverted means we should never get a revert if the sum didn’t overflow.

Finally, the else block shown below handles overflow cases by expecting a revert where _sum exceeds max_uint256.

else {

add@withrevert(x, y);

assert lastReverted;

}

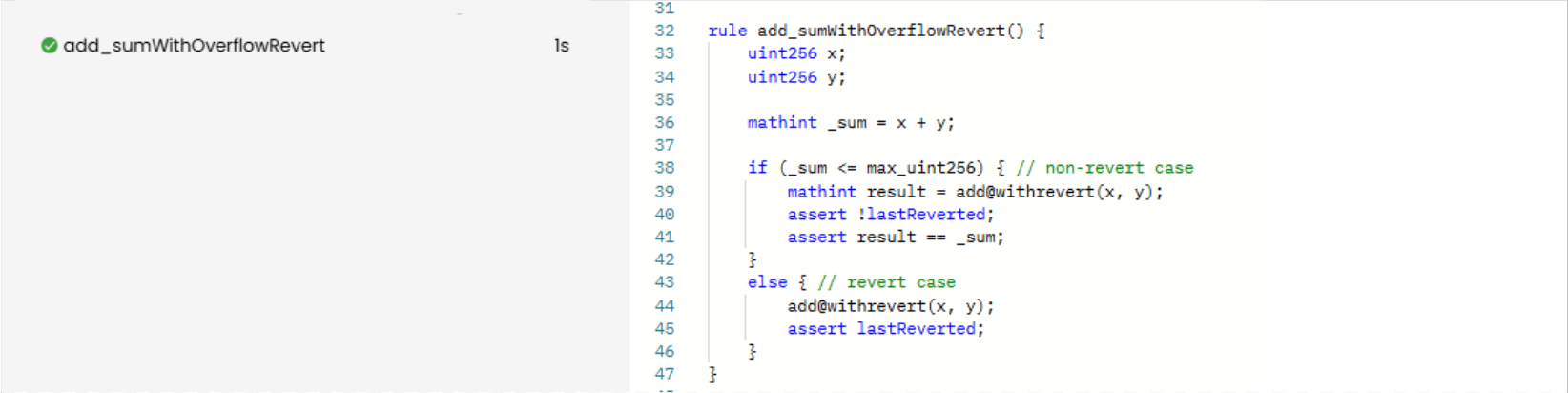

As expected, the CVL rule is VERIFIED:

Prover run: link

This example shows that Solidity functions can be invoked and assertions can be performed within conditional blocks or branches.

Variable Assignments In An if Statement

Next, we will formally verify the gas-optimized max function from the Solady library.

Below is the Solady max function implementation. Even though it may not be immediately obvious, it returns the greater of x and y. If x equals y, the function simply returns x.

/// Solidity

function max(uint256 x, uint256 y) external pure returns (uint256 z) {

assembly {

z := xor(x, mul(xor(x, y), gt(y, x)))

}

}

Notice that we have changed the visibility from internal to external to eliminate the need for a harness file, which is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Explaining the inner workings of this assembly implementation is also beyond the scope of this chapter. However, if you’re curious, here’s a video that covers the details in under five minutes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nDUQIk4oqQ.

Now, let’s proceed with the formal verification of the Solady max function. It has two variations: one for unsigned integers and another for signed integers. Since both follow the same fundamental concept, we will focus on the unsigned integer variation.

Here is a starting CVL rule to verify the Solady max function, but we will simplify this shortly:

/// CVL

rule max_returnMax() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

if (x >= y) {

mathint max = max@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert max == x;

}

else {

mathint max = max@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert max == y;

}

}

In the rule above, the if block verifies that when x > y, the max value is x, or if x = y, it simply returns x since both values are identical. The else block covers the remaining case, where x < y, making y the maximum value. In either case, we do not allow for reverts as the function should never revert.

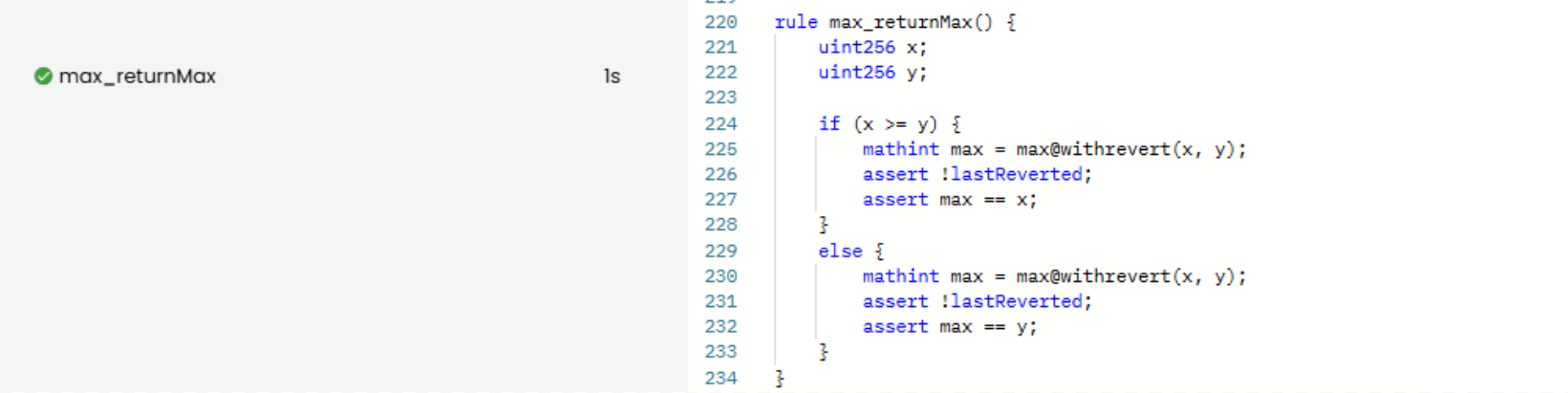

As expected this rule is VERIFIED:

Prover run: link

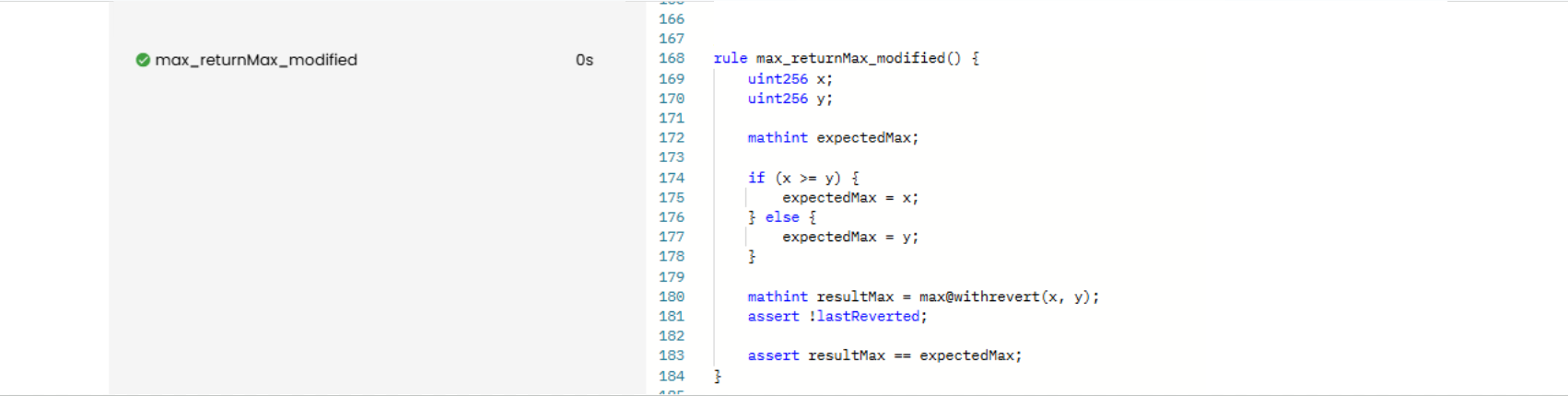

Function invocations and assertions do not need to be inside the if/else block. We can move the function calls outside the if block and compute the expected results inside the if block:

/// CVL

rule max_returnMax_modified() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint expectedMax;

if (x >= y) {

expectedMax = x;

} else {

expectedMax = y;

}

mathint resultMax = max@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert resultMax == expectedMax;

}

Prover run: link

Moving function invocations outside of an if statement leads to more efficient CVL code, since functions are invoked only once instead of within each conditional branch. The impact may not be noticeable yet, but for more complex rules, this approach can be beneficial, as we will show in the next section.

Reducing Verifier Complexity, An Example With mulDivUp

mulDivUp() is a function that multiplies two unsigned integers, divides the product by another unsigned integer, and rounds up if a remainder exists. If there is no remainder, it returns the quotient as is. For example, 5 / 2 is 2, but mulDivUp(5, 2) results in 3 due to rounding up. In contrast, 4 / 2 is 2, and mulDivUp(4, 2) also results in 2, as there is no remainder.

Also, it reverts in two cases: when the divisor is zero or when the numerator (product of x and y) exceeds max_uint256.

The implementation we will use is from Solmate’s mulDivUp(), a gas-efficient function written in assembly. We have slightly modified the code by changing its visibility from internal to external to avoid using a harness file.

Here’s the Solmate mulDivUp() function:

/// Solidity

uint256 internal constant MAX_UINT256 = 2**256 - 1;

function mulDivUp(

uint256 x,

uint256 y,

uint256 denominator

) external pure returns (uint256 z) {

assembly {

// Equivalent to require(denominator != 0 && (y == 0 || x <= type(uint256).max / y))

if iszero(mul(denominator, iszero(mul(y, gt(x, div(MAX_UINT256, y)))))) {

revert(0, 0)

}

// If x * y modulo the denominator is strictly greater than 0,

// 1 is added to round up the division of x * y by the denominator.

z := add(gt(mod(mul(x, y), denominator), 0), div(mul(x, y), denominator))

}

}

The assembly code explanation is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the comments describe each line’s function.

In the lines below,

// Equivalent to require(denominator != 0 && (y == 0 || x <= type(uint256).max / y))

if iszero(mul(denominator, iszero(mul(y, gt(x, div(MAX_UINT256, y)))))) {

revert(0, 0)

}

it defines the revert behavior. It enforces that the denominator must not be zero to prevent division by zero. Additionally, it guarantees that x * y does not exceed MAX_UINT256 and triggers a revert if it does.

In the final line, it defines the rounding behavior:

// If x * y modulo the denominator is strictly greater than 0,

// 1 is added to round up the division of x * y by the denominator.

z := add(gt(mod(mul(x, y), denominator), 0), div(mul(x, y), denominator))

If the remainder of x * y divided by denominator is greater than zero, one is added to the result to round up; otherwise, the result remains unchanged.

Now that we know what the function is trying to do, we can now proceed with the formal verification.

Developing Specifications For mulDivUp

Here is an initial specification that captures the behavior of the Solmate mulDivUp() function, and the explanation follows afterwards:

/// CVL

rule mulDivUp_roundOrRevert() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

if (denominator == 0) { // catches revert condition: if denominator is zero

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert lastReverted;

}

else if (x * y > max_uint256) { // catches revert condition: multiplication overflows a max_uint256 value

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert lastReverted;

}

else { // catches all non-revert conditions

if (x * y % denominator == 0) { // if there's no remainder after x * y and denominator division

mathint result = mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == x * y / denominator;

}

else { // if there's a remainder after x * y and denominator division

mathint result = mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == (x * y / denominator) + 1;

}

}

}

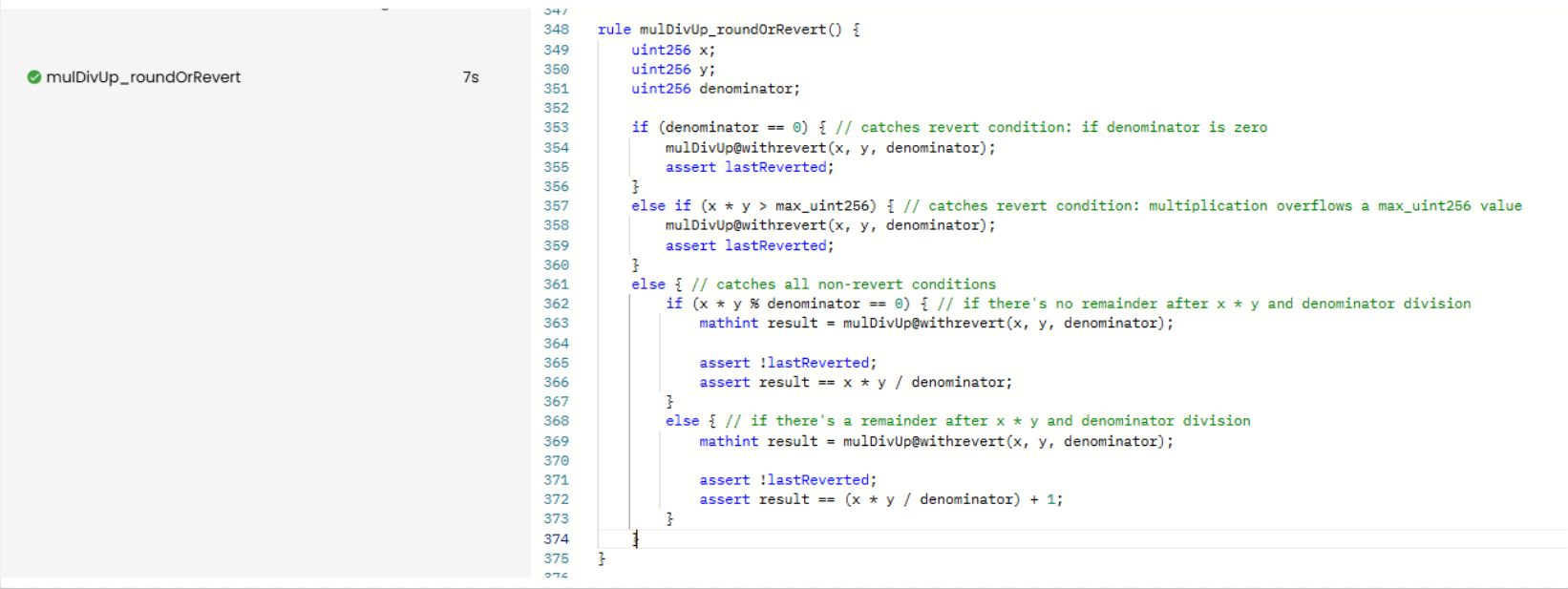

When we run the Certora Prover, the Solmate mulDivUp() is verified to be correct:

Prover run: link

Notice from the code above that we can use multiple conditional branches with else if, and nothing prevents us from using nested if/else statements. However, to avoid nesting if statements, which makes the rule harder to read, we can re-arrange the conditions.

The lines below handle the revert conditions:

if (denominator == 0) {

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert lastReverted;

}

else if (x * y > max_uint256) {

mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert lastReverted;

}

If any of these conditions are met, the branch asserts lastReverted, meaning the function reverts. While we could combine these two revert conditions into one, we will address this later when discussing code optimization.

If these two revert conditions are not met, execution moves to the else statement, where the rounding behavior is verified. Within the else block, there is another set of if/else statements that define the specification for rounding behavior.

In the else block, as you will see below, the if condition checks whether the product of x and y, when taken modulo the denominator, has a remainder of zero. In this case, no rounding up is needed, so the return value is x * y / denominator. However, in the else branch, where the modulo operation results in a remainder greater than zero, rounding up is performed by adding 1 to x * y / denominator.

else {

if (x * y % denominator == 0) {

mathint result = mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == x * y / denominator;

}

else {

mathint result = mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == (x * y / denominator) + 1;

}

}

We learned that if/else can consolidate verifications within a single rule instead of creating multiple rules. However, it also has its drawbacks. As the function being verified becomes more complex, the specification grows in complexity disproportionately, which we will discuss next.

Path Explosion

Using if/else tends to create conditional branches, invoke functions, and perform assertions within the conditional blocks themselves. When this happens, the Prover tests all cases in every branch, increasing the number of scenarios that must be evaluated and naturally slowing down rule execution.

Optimized CVL Rule For mulDivUp

Below is the optimized rule, and we will explain the changes we made next.

/// CVL

rule mulDivUp_roundOrRevert_optimized() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mathint result = mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

if (denominator == 0 || x * y > max_uint256) {

assert lastReverted;

}

else {

if (x * y % denominator == 0) {

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == x * y / denominator;

}

else {

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == (x * y / denominator) + 1;

}

}

}

The first change we made was combining the revert conditions into a single if statement: if (denominator == 0 || x * y > max_uint256) { … }.

We then removed all mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator) function invocations from the branches and isolated them into a single call. This improves efficiency by avoiding redundant function calls within conditional blocks.

Prover Runtime Benchmarks

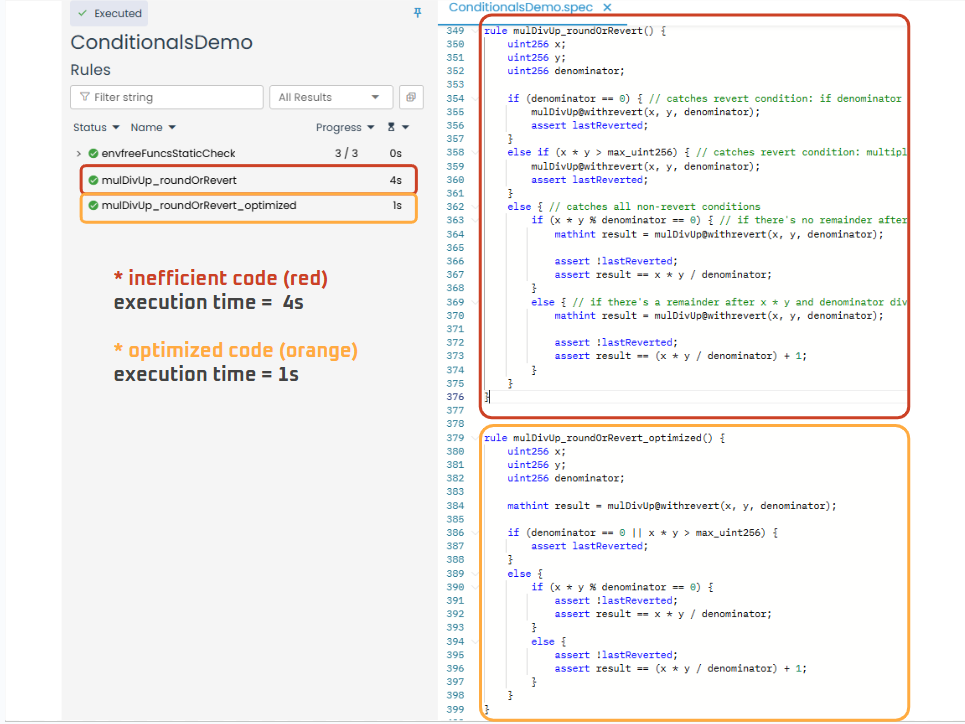

Below is the comparison of execution time between the inefficient code and the optimized code:

Prover run: link

Looking at the Prover report above, inefficient use of if/else can significantly slow down rule execution. Comparing the inefficient and optimized versions, the inefficient code takes four times longer to execute than the optimized code. This issue only worsens as we develop specifications for real projects with complex smart contracts.

Note_:_ To compare two rules based on their execution times, we must run them simultaneously and ensure that the cache is turned off by adding --cache none in the CLI command.

All Conditions Must Be Handled

The if/else construct inherently requires that all conditions be accounted for. The if block handles specific cases, while the else block acts as a catch-all for any cases not explicitly mentioned in the if.

This is both a good and a bad thing. It is good because it ensures that all conditions are considered, preventing missed cases. However, sometimes we are only interested in the outcome of a specific condition, and having to account for all conditions can hold us back and consume a lot of time.

For example, let’s explicitly omit one revert case: x * y > max_uint256 from this rule, and the Prover will show the counterexample where x * y exceeds max_uint256.

/// CVL

rule mulDivUp_roundOrRevert_omittedARevertCase() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 denominator;

mathint result = mulDivUp@withrevert(x, y, denominator);

if (denominator == 0) { // intentionally omitted `x * y > max_uint256`

assert lastReverted;

} else {

if (x * y % denominator == 0) {

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == x * y / denominator;

} else {

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == (x * y / denominator) + 1;

}

}

}

If we’re only interested in the revert condition denominator == 0, we cannot consider it exclusively using an if/else construct (technically, we can, but it’s hacky and best avoided). We must account for all other revert cases as well.

The idiomatic way to handle this is with the implication operator, which will be covered in the next chapter.

Ternary Operator

The ternary operator is a concise alternative to if/else statements for simple conditional logic. Using the syntax condition ? expressionA : expressionB, it returns expressionA if the condition is true; otherwise, it returns expressionB.

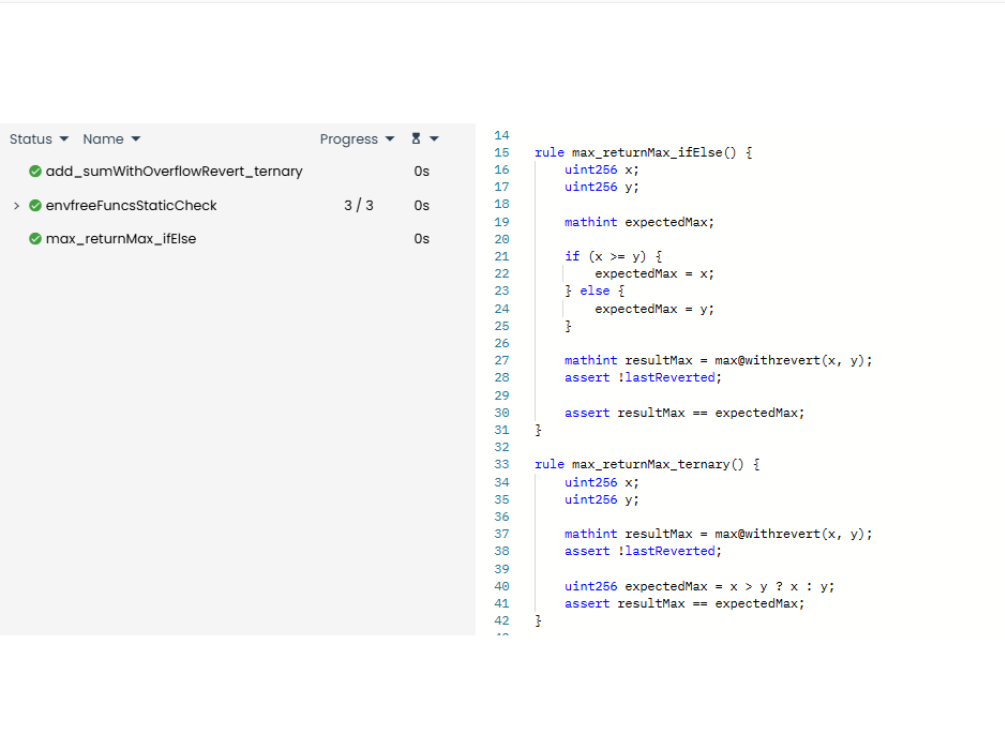

Our previous example, the max() function, can be directly translated using a ternary expression, as shown below:

/// CVL

rule max_returnMax_ifElse() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint expectedMax;

if (x >= y) {

expectedMax = x;

} else {

expectedMax = y;

}

mathint resultMax = max@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert resultMax == expectedMax;

}

rule max_returnMax_ternary() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint resultMax = max@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

uint256 expectedMax = x > y ? x : y;

assert resultMax == expectedMax;

}

Prover run: link

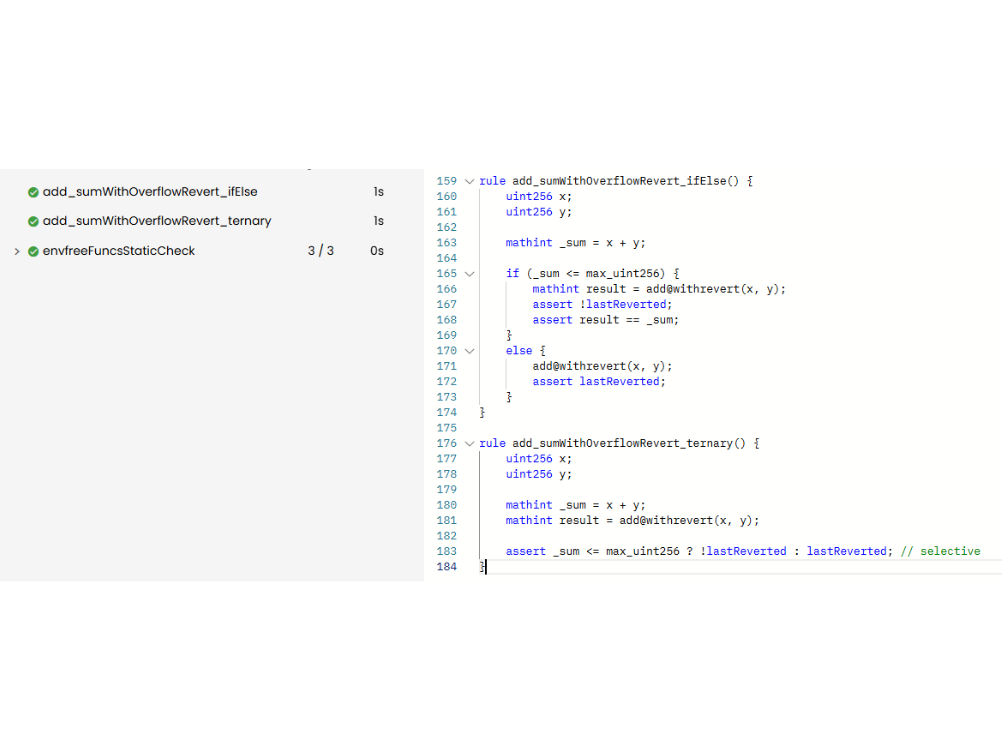

However, in another example, add(), we can also use a ternary expression, but only selectively. We cannot include all potential execution paths as shown below:

/// CVL

rule add_sumWithOverflowRevert_ifElse() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint _sum = x + y;

if (_sum <= max_uint256) {

mathint result = add@withrevert(x, y);

assert !lastReverted;

assert result == _sum;

}

else {

add@withrevert(x, y);

assert lastReverted;

}

}

rule add_sumWithOverflowRevert_ternary() {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

mathint _sum = x + y;

mathint result = add@withrevert(x, y);

assert _sum <= max_uint256 ? !lastReverted : lastReverted; // selective

}

Prover run: link

The reason we cannot account for other conditions is that the return expressions in a ternary operation must be of the same type. Hence, asserting it like this: _sum <= max_uint256 ? _sum : lastReverted is not possible because _sum is of type mathint, while lastReverted is a boolean.

Lastly, for mulDivUp(), we also cannot translate this directly; we have to pick properties one by one and apply the ternary to each, similar to what we did with add().

Summary

if/elseis intuitive due to familiarity from other programming languages.- Too many conditional branches slow down the Prover, but optimization can improve efficiency.

if/elserequires handling all conditions, making it impractical for isolated case verification.- The ternary operator provides a concise alternative but does not work when the return types differ.

Exercises for the reader

- Formally verify Solady min always returns the min.

- Formally verify Solady zeroFloorSub returns

max(0, x - y). In other words, ifxis less thany, it returns0. Otherwise, it returnsx - y.