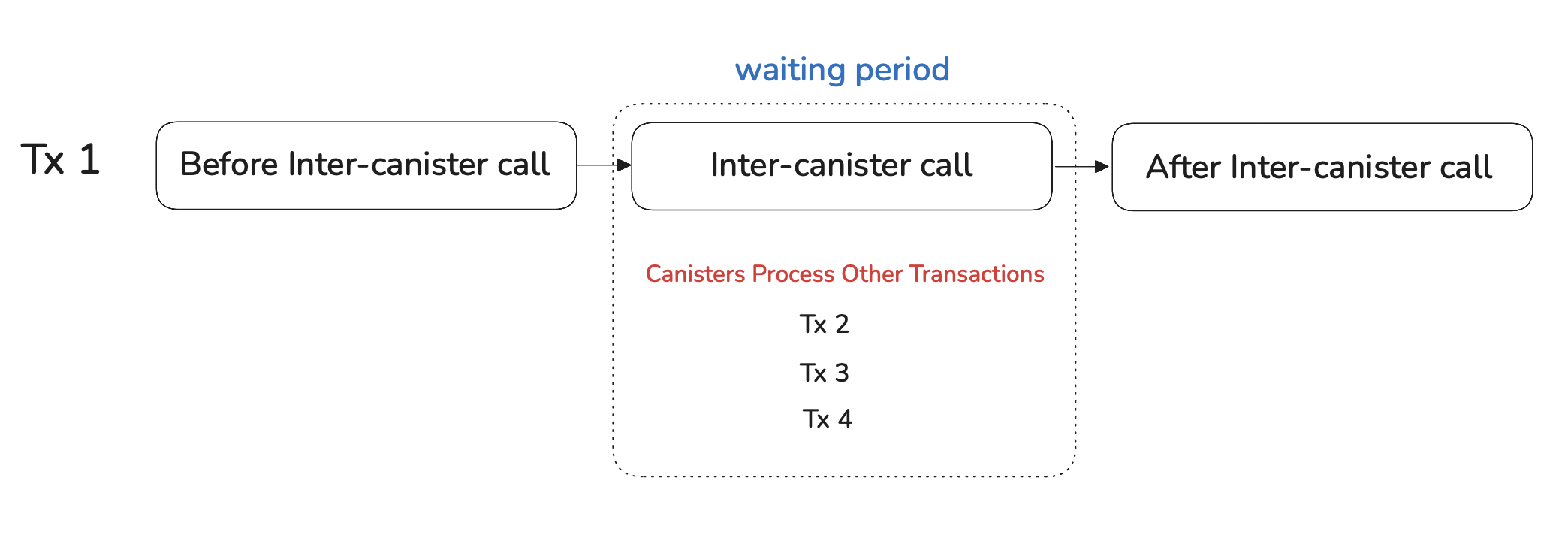

When a canister makes an inter-canister call and waits for the response, it does not block or halt execution. Instead, the canister keeps executing other transactions until the inter-canister call returns.

The diagram below illustrates this behavior. The canister begins processing Tx₁, which performs an inter-canister call. While Tx₁ is waiting for the response, the canister continues processing Tx₂, Tx₃, and Tx₄ sequentially. Once the response arrives, the canister resumes execution of Tx₁.

In this article, we explore what non-blocking execution means in practice. Specifically, we demonstrate how concurrent calls can observe and modify intermediate canister state, and why this requires extra care when writing asynchronous functions.

Intermediate State Is Observable During Async Calls

To see how non-blocking execution affects visibility of state, consider two canisters: A and B.

Canister A exposes an asynchronous function foo() that increments a state variable X twice:

- Once before making an inter-canister call to

B.bar(), and - Once after that call returns.

use std::cell::RefCell;

use candid::Principal;

use ic_cdk::{call::Call, update};

thread_local! {

static X: RefCell<u64> = RefCell::new(0);

}

#[update]

async fn foo(callee: Principal) -> bool {

increment();

// (2) non-blocking wait for B.bar()

let _result = Call::bounded_wait(callee, "bar").await;

increment();

true

}

#[update]

fn increment() {

X.with_borrow_mut(|cell| *cell += 1);

}

#[ic_cdk::query]

fn get_x() -> u64 {

X.with_borrow(|cell| *cell)

}

ic_cdk::export_candid!();

Canister B provides a deliberately slow function bar(), which takes roughly 13 seconds to execute.

use ic_cdk::update;

#[update]

fn bar() -> u64 {

// Computationally heavy and slow

let limit: u64 = 3_900_000_000;

let mut total: u64 = 0;

for i in 0..limit {

// Do something simple but not optimizable to a no-op

total = total.wrapping_add(i ^ (i >> 3));

}

total

}

ic_cdk::export_candid!();

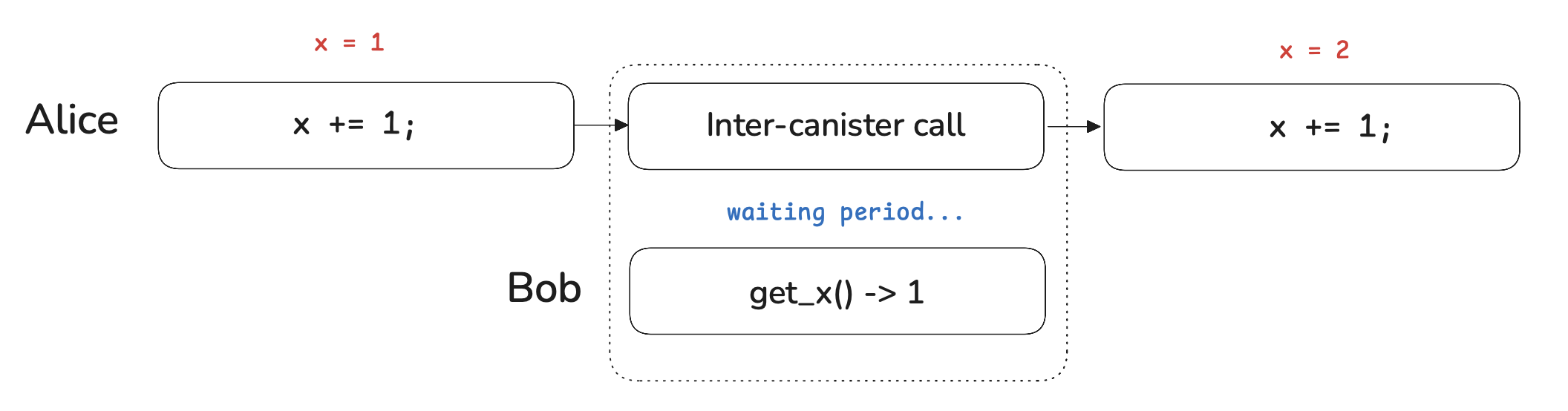

Now suppose Alice calls A.foo() when X = 0.

foo()first incrementsXfrom0to1.- It then makes an asynchronous call to

B.bar()and suspends execution while waiting for the response.

At this point, the key observation is that the increment to X has already been committed. While foo() is suspended, the canister is free to process other incoming messages.

During this waiting period, Bob can call get_x() and observe the current state of the canister. His call will return 1, reflecting the state committed before the inter-canister call.

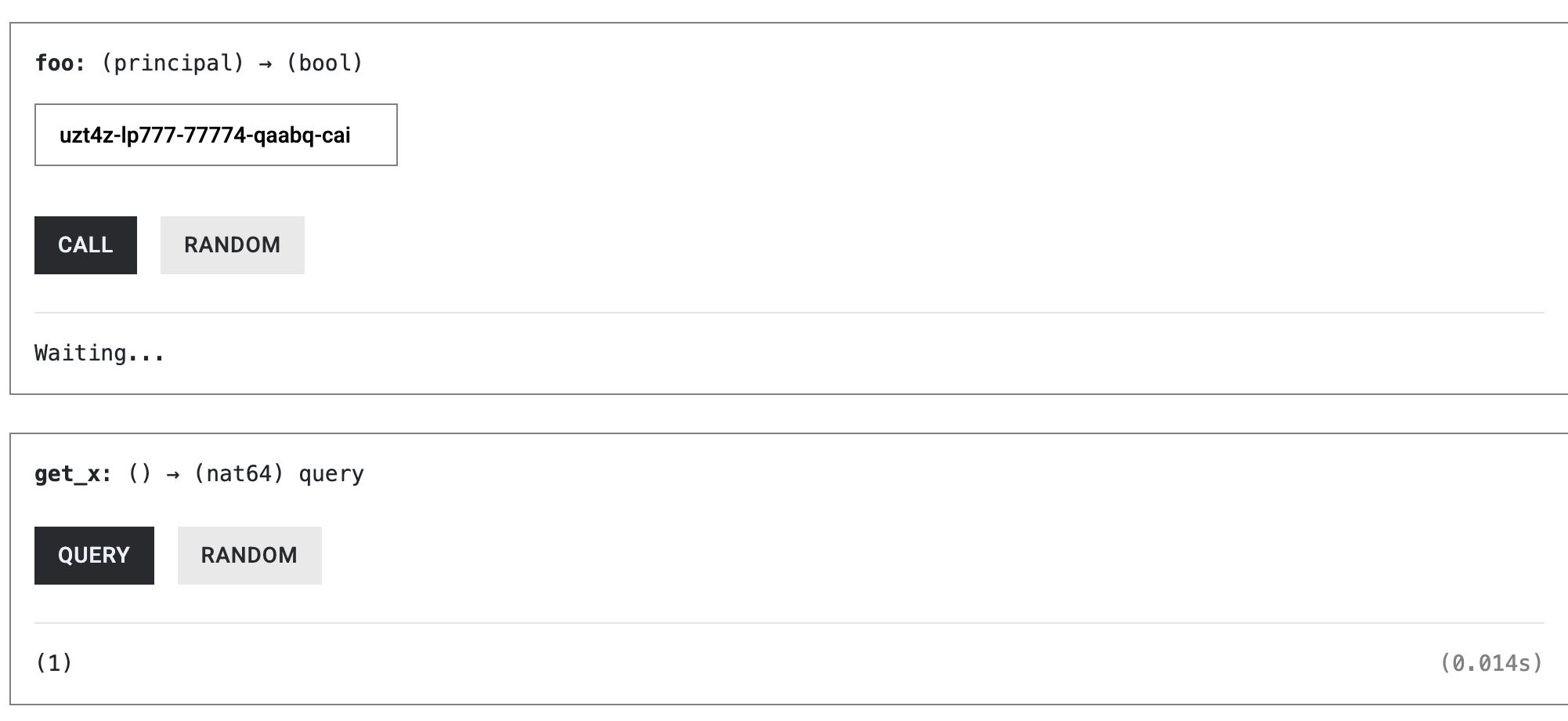

You can reproduce this behavior yourself:

- Deploy canisters A and B.

- Call

A.foo(). - Immediately call

get_x()whilefoo()is still waiting.

It should return 1 as shown below:

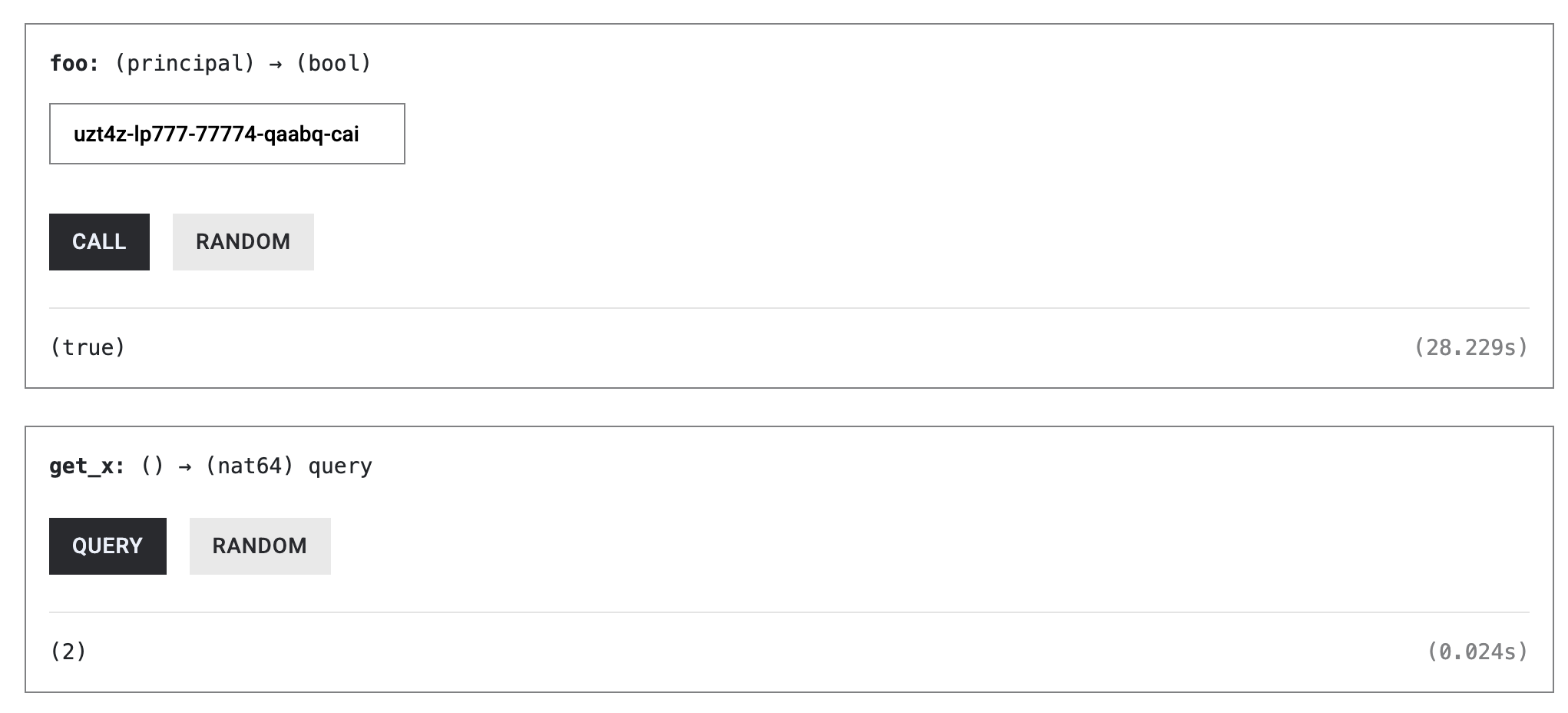

Once B.bar() finishes and foo() resumes, foo() increments X again and completes. A subsequent call to get_x() should now returns 2.

- The first

get_x()runs whilefoo()is suspended and observes the intermediate state. - The second

get_x()runs afterfoo()finishes and observes the final state.

This example demonstrates an important property of the Internet Computer’s execution model: state changes made before an await are immediately visible to other calls.

In the next section, we’ll see that other calls can do more than merely observe this intermediate state — they can modify it, causing an asynchronous function to resume in a different state than the one it originally started with.

Intermediate State Can Be Modified While an Async Call Is Suspended

So far, we’ve seen that state changes made before an await become immediately observable to other calls. More importantly, those calls are not limited to passive observation — they can actively modify the canister’s state while an asynchronous function is suspended.

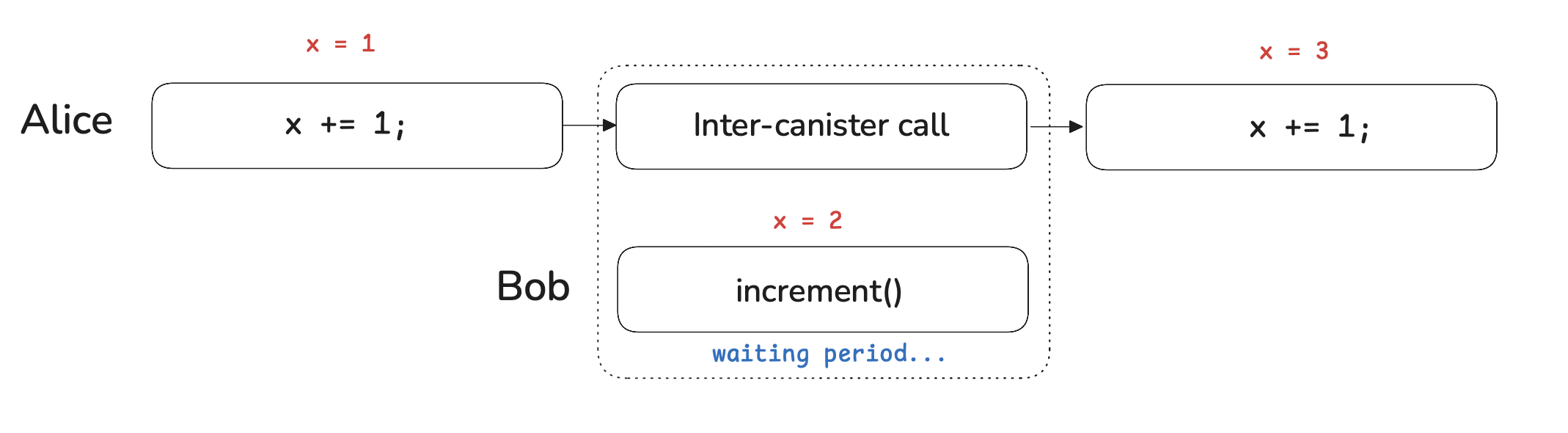

Revisiting the previous example, suppose Bob calls increment() while Alice’s call to foo() is still waiting on B.bar().

Here is the sequence of events:

- Alice calls

foo()whenX = 0. foo()increments X to 1 and then awaits the response fromB.bar().- While

foo()is suspended, Bob callsincrement(), updatingXfrom 1 to 2. - When

foo()resumes, it observes the new state (X = 2) and increments it again, resulting inX = 3.

The key takeaway is that an asynchronous function on the Internet Computer does not execute against a single, stable snapshot of canister state. Any state that was committed before an await can be changed by other messages before the function resumes.

As a result, asynchronous functions may resume in a different state than the one they started with, even if they themselves made no additional changes during the waiting period.

In the next section, we’ll examine what this means for real canister logic.

Example of An Async Function Resuming Into a New Canister State

In the previous section, we saw that other calls can modify a canister’s state while an asynchronous function is suspended. We now make this effect explicit by adding a simple consistency check to detect whether the state has changed while foo() was waiting.

We extend canister A to record two snapshots of the state variable X:

x_before: the value of X immediately before the inter-canister call, andx_after: the value of X immediately after the call returns.

If these two values differ, it means that some other transaction modified X while foo() was suspended. In that case, foo() returns false early instead of proceeding.

**use** std**::**cell**::**RefCell;

**use** ic_cdk**::**{call**::**Call, update};

**use** candid**::**Principal;

thread_local!{

static X : RefCell<u64> = RefCell::new(0);

}

#[update]

**async** **fn** **foo**(callee**:**Principal) **->** bool {

increment();

// value of x BEFORE inter-canister call

let x_before = X.with_borrow(|cell|*cell);

let _ = Call::bounded_wait("B", "bar").await;

// value of x AFTER inter-canister call

let X_after = X.with_borrow(|cell|*cell);

// check that the X hasn't changed, return false if it has

if X_before != X_after {

return false;

}

increment()

return true;

}

#[ic_cdk::update]

fn increment() {

X.with_borrow_mut(|cell| *cell +=1 );

}

#[query]

fn get_x() -> u64 {

X.with_borrow(|cell|*cell)

}

ic_cdk::export_candid!()

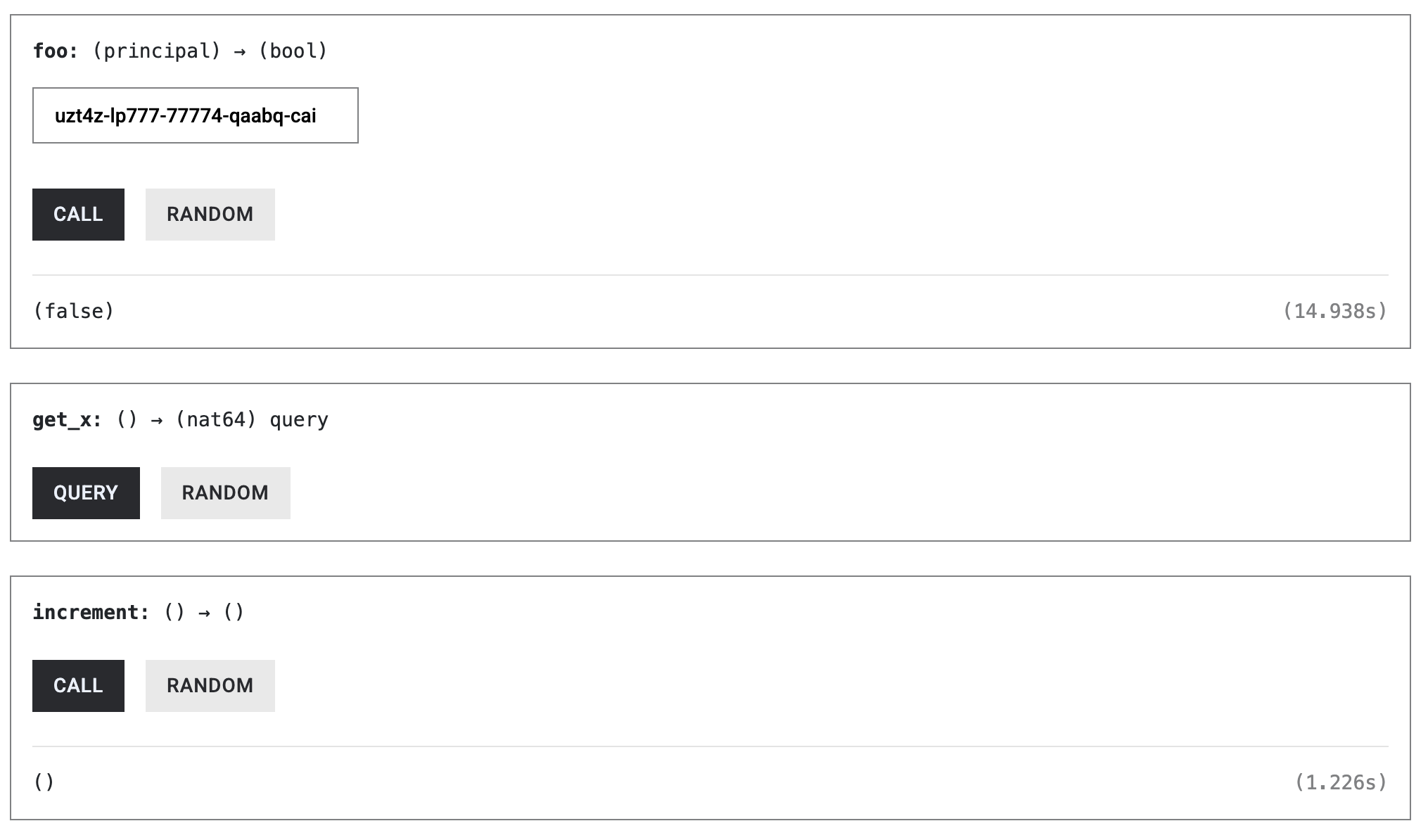

To observe this behavior, redeploy canister A and call foo(). While foo() is waiting on B.bar(), call increment() from another identity. When foo() resumes, it will detect that x_before ≠ x_after and immediately return false.

This example highlights a crucial implication of the Internet Computer’s non-blocking execution model: local variables that capture state before an await can become stale by the time execution resumes.

As a result, asynchronous canister functions must be written defensively. Any logic that depends on state read before an inter-canister call must be revalidated, recomputed, or explicitly guarded when the function resumes.

Designing Correct Async Code in a Non-Blocking Canister Model

The examples above demonstrate a fundamental property of the Internet Computer’s execution model: a canister does not remain idle while waiting for an asynchronous call to return. Instead, it continues processing other messages, which may observe or modify the canister’s state.

As a result, asynchronous functions must be written with the assumption that state may change across an await. Any design that implicitly relies on the state remaining unchanged while an inter-canister call is in flight is incorrect.

A particularly dangerous pattern is to:

- read some state,

- perform an inter-canister call, and then

- reuse the previously read value to update the state.

The following example illustrates this mistake.

// Example vault contract

async fn withdraw(amount: u64) -> Result<(), Error> {

// (1) Read the vault's balance

let balance = get_balance();

// check if they enough funds

// (2) withdraw icp tokens to user

Call::bounded_wait("icp_ledger", "transfer", amount).await;

// (3) Use the old `balance` to calculate for the new balance

set_balance(balance - amount); // may be stale!

Ok(())

}

While the function is suspended at the await, other messages may execute:

- another user might deposit,

- another withdrawal might already have reduced the balance,

- an administrative operation may have updated state.

When the function resumes, the local variable balance may no longer reflect the canister’s actual state, yet it is still being used to compute the new balance. This kind of bug is subtle, easy to miss in review, and difficult to detect in testing.

To write correct asynchronous canister code, we must instead acknowledge that state changes may be committed before an await, and structure our logic accordingly.

One common approach is to anticipate the state change before making the inter-canister call, then either:

• keep the change if the call succeeds, or

• explicitly roll it back if the call fails.

Because the state may continue to change while the function is suspended, rollback logic must also re-read the current state to ensure that only the intended changes are undone.

// Anyone can withdraw

async fn withdraw(amount: u64) -> bool {

// Read the vault's balance

let balance = get_balance();

// Anticipate the change

set_balance(balance - amount);

// withdraw tokens to caller

let result = Call::bounded_wait("icp_ledger", "transfer", amount).await;

// explicitly handle the inter-canister call

if result.is_ok(){

// state-changes were already made, do nothing

// return ok

return true;

} else{

// result is error

// Read the new vault's balance

let new_balance = get_balance();

// add the balance back to the vault

set_balance(balance + amount);

// return false indicating that the withdraw failed

return false;

}

}

This pattern acknowledges that state changes may be committed before the await, avoids relying on stale local variables after an inter-canister call, and correctly recomputes and rolls back state when the call fails.

One of the most complex concepts to grasp is ICP’s asynchronous execution model. Now that we have covered it, when performing an HTTP Outcall, which is an asynchronous System API that allows canisters to perform HTTP requests to web2 APIs, it also follows the pattern above.

In the next article, we’ll learn how to send Cycles between canisters, which is similar to sending Ether between Solidity contracts.