An invariant is a property that must always hold true after a smart contract is deployed and throughout its execution. At first glance, verifying an invariant may seem straightforward: assume that the invariant holds before a function call, run the function, and confirm it still holds afterward.

In practice, this process is rarely so simple. The Certora Prover operates in a symbolic world where it explores all possible states of a contract, not just those that would realistically occur in a deployed system. This exhaustive, symbolic exploration is fundamental to its design; it’s what allows the Prover to find bugs in scenarios developers might never consider.

However, not every symbolic state the Prover explores is a valid or reachable state within the context of the contract’s business logic. Without additional guidance, the Prover may start from or reason about “impossible” states or conditions that could never arise in a real blockchain execution. When this happens, the Prover might flag a violation even though the contract itself is correct, simply because the analysis began from an invalid assumption.

To prevent such false violations, CVL provides the preserved block, a mechanism that allows us to specify extra assumptions about realistic contract behavior. These assumptions help the Prover focus on valid and relevant execution paths, ruling out states that are logically or contextually impossible.

In this chapter, we’ll explore the role of preserved blocks in formal verification. We’ll discuss why they’re necessary, how to write them in CVL, and how they help ensure that invariants are checked only under realistic conditions. We’ll also apply this concept to a practical example by verifying that, in the WETH contract, the contract’s ETH balance always matches or exceeds its total token supply.

To understand their role more clearly, let’s first revisit how the Prover checks whether a function preserves an invariant, and why this process can sometimes break down.

Why Invariants Need Additional Assumptions

As we know, when verifying invariants, the Prover follows a structured reasoning process similar to mathematical induction:

- Initial-state Check (Base Case): The Prover first verifies that the invariant holds immediately after the contract’s constructor finishes executing. This establishes the invariant as true at the starting point.

- Assumption (Pre-state): For each public and external function, the Prover assumes that the invariant holds before the function executes.

- Symbolic Execution and Post-state Check: It then symbolically executes the function across all possible inputs and control-flow paths, and verifies that the invariant still holds afterward.

If the invariant satisfies all these checks, it is considered preserved for all contract executions. But here lies the difficulty: the Prover does not restrict itself to realistic execution paths. It also explores highly unlikely, and even impossible, states.

For example, while verifying the ERC-20 invariant “the sum of all account balances must always equal the total token supply,” the Prover may explore an execution path where the contract ends up calling its own functions. In practice, this situation never occurs, since ERC-20 functions like transfer are intended to be called only by external users or other contracts. However, because the Prover systematically explores all possible callers, it also considers traces where the contract invokes its own functions.

Such self-calls can produce absurd scenarios where balances and the total token supply appear inconsistent, leading the Prover to report a violation even though no real execution could trigger it. These are classic examples of false violations: the invariant appears broken only because the Prover has reasoned about states that cannot happen in reality.

This is where preserved blocks come in. Preserved blocks allow us to introduce additional assumptions during invariant verification, guiding the Prover to ignore impossible or irrelevant states and focus only on realistic ones.

Now that we understand why preserved blocks are necessary, let’s move on to how they are written in CVL.

How to Define a Preserved Block?

A preserved block is a special construct in CVL that lets us add extra assumptions when proving an invariant. Think of it as giving the Prover a small “hint” about how the system actually behaves, so it doesn’t waste time exploring impossible scenarios.

We define a preserved block right after the invariant expression, using the preserved keyword. The simplest form looks like this:

invariant invariant_name()

invariant_expression

{

preserved {

// assumptions about the invariant

}

}

Sometimes, we don’t want a preserved block to apply everywhere — only for a particular function, or only with certain environmental details (like msg.sender or msg.value). In that case, we can extend the syntax with an optional function signature and an optional with clause (to access the transaction environment):

invariant invariant_name(param_1, param_2,...)

invariant_expression;

{

preserved functionName(type arg, ...) with (env e) {

// additional assumptions applicable only for this particular function

}

}

Both generic preserved blocks and function-specific preserved blocks apply during the induction step of invariant checking. They are executed after the invariant is assumed to hold in the pre-state but before the corresponding method is symbolically executed, ensuring that the Prover starts each induction step from a state that is both mathematically valid and contextually realistic.

So far, preserved blocks determine the assumptions under which each relevant function is analyzed. In some cases, however, we may also want to restrict which functions the invariant is checked against in the first place. CVL provides a filter block, written as filtered { … }, for this purpose. (You can read more about filter block at here )

invariant invariant_name()

invariant_expression;

filtered {

// restrict which functions are checked

}

{

preserved functionName(type arg, ...) with (env e) {

// assumptions or requireInvariant statements

}

}

When a filter block is present, the invariant is checked only against the functions included in the filter, and any preserved blocks apply within that restricted set. For this reason, the preserved block is written after the filter block.

A filter block restricts which functions the invariant is checked against. A generic preserved block (preserved with (env e) { ... }) then applies to every function in that filtered set. A function-specific preserved block (preserved functionName(…) with (env e) { ... }) applies only when the Prover is checking that named function. If the named function is not included by the filter, that preserved block has no effect.

In short, filters narrow down where an invariant is applied, and preserved blocks describe what must still hold when those functions are executed. Used together, they give the Prover a clear path to check invariants without being distracted by irrelevant or impossible states.

In practice, however, preserved blocks are generally preferred over filter blocks when an invariant fails due to unrealistic symbolic execution. Both mechanisms restrict the Prover’s search space and must be used carefully to avoid weakening a proof, but filters are riskier because they remove entire functions from invariant checking.

Preserved blocks are usually safer because they constrain assumptions about the state or execution environment rather than excluding behavior altogether. As a result, they are better suited for ruling out impossible states while still ensuring that the invariant is checked against all relevant contract functionality.

Now that we’ve covered the theory and syntax, let’s see how preserved blocks work in practice by applying them to a real contract: Solady’s WETH.

Putting It All Together: Verifying a WETH Invariant

To put everything into context, let’s verify an invariant of the Solady WETH contract — an ERC-20 implementation that represents Ether (ETH) in a 1:1 ratio with WETH tokens. A key property of this contract is that its ETH balance must always be greater than or equal to the total number of WETH tokens in circulation.

Defining Our WETH Invariant

To verify this invariant, follow the steps below:

- Inside your Certora project directory, create a new file named

ERC20.solin thecontractssubdirectory, and copy this code from Solady into it. - Create another file named

WETH.solin the samecontractssubdirectory, and copy this code into it. - In the

specssubdirectory, create a new file namedweth.spec. - Inside

weth.spec, define the invarianttokenIntegrity()as follows:

invariant tokenIntegrity()

nativeBalances[currentContract] >= totalSupply();

Note: In CVL, nativeBalances is a mapping of the native token balances — for example, ETH on Ethereum. The balance of an address a can be expressed using nativeBalances[a]. The identifier currentContract refers to the main contract being verified. Therefore, nativeBalances[currentContract] represents the native token balance of the contract being verified.

- Add a methods block that includes the function signature of

totalSupply():

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns (uint256) envfree;

}

invariant tokenIntegrity()

nativeBalances[currentContract] >= totalSupply();

- In the

confssubdirectory, create a configuration file namedweth.conf:

{

"files": [

"contracts/WETH.sol:WETH"

],

"verify": "WETH:specs/weth.spec",

"optimistic_loop" : true,

"msg": "Check WETH contract integrity"

}

Running the Verification

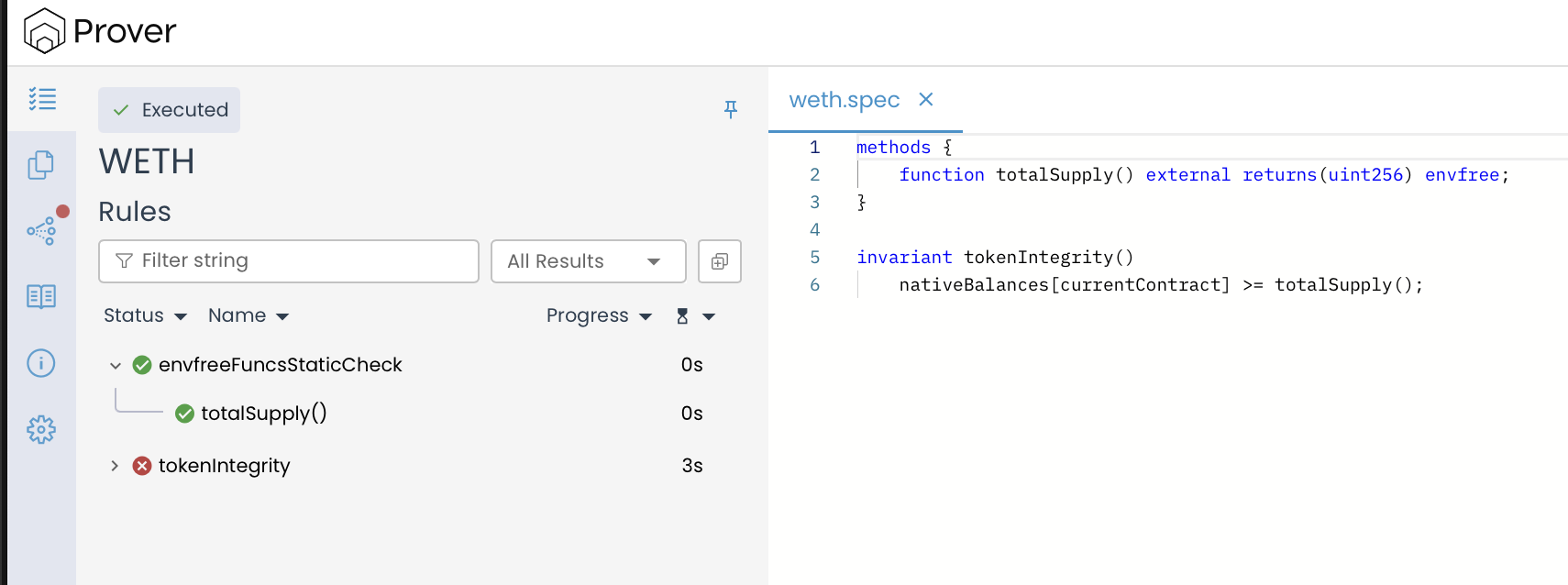

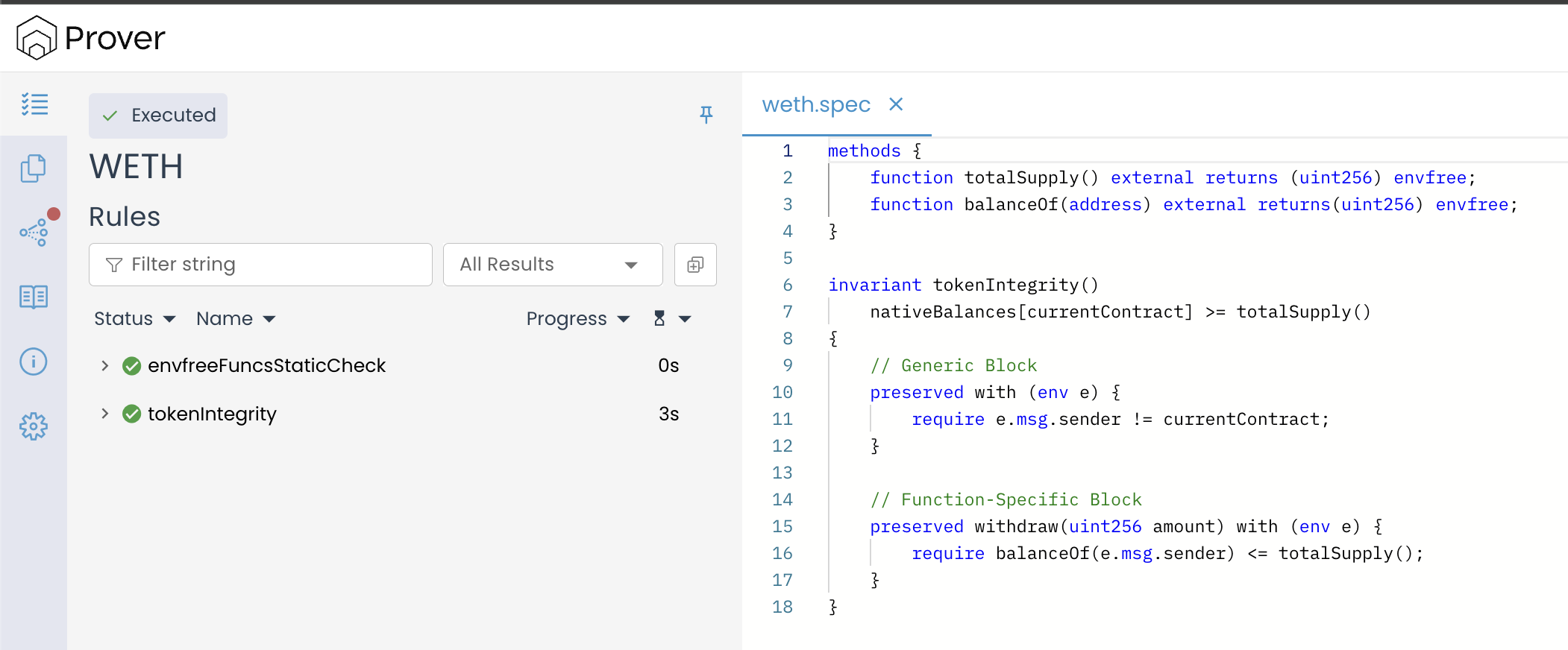

Once you have executed all the steps above, run the certoraRun confs/weth.conf command to verify our specification and view a result similar to the image below:

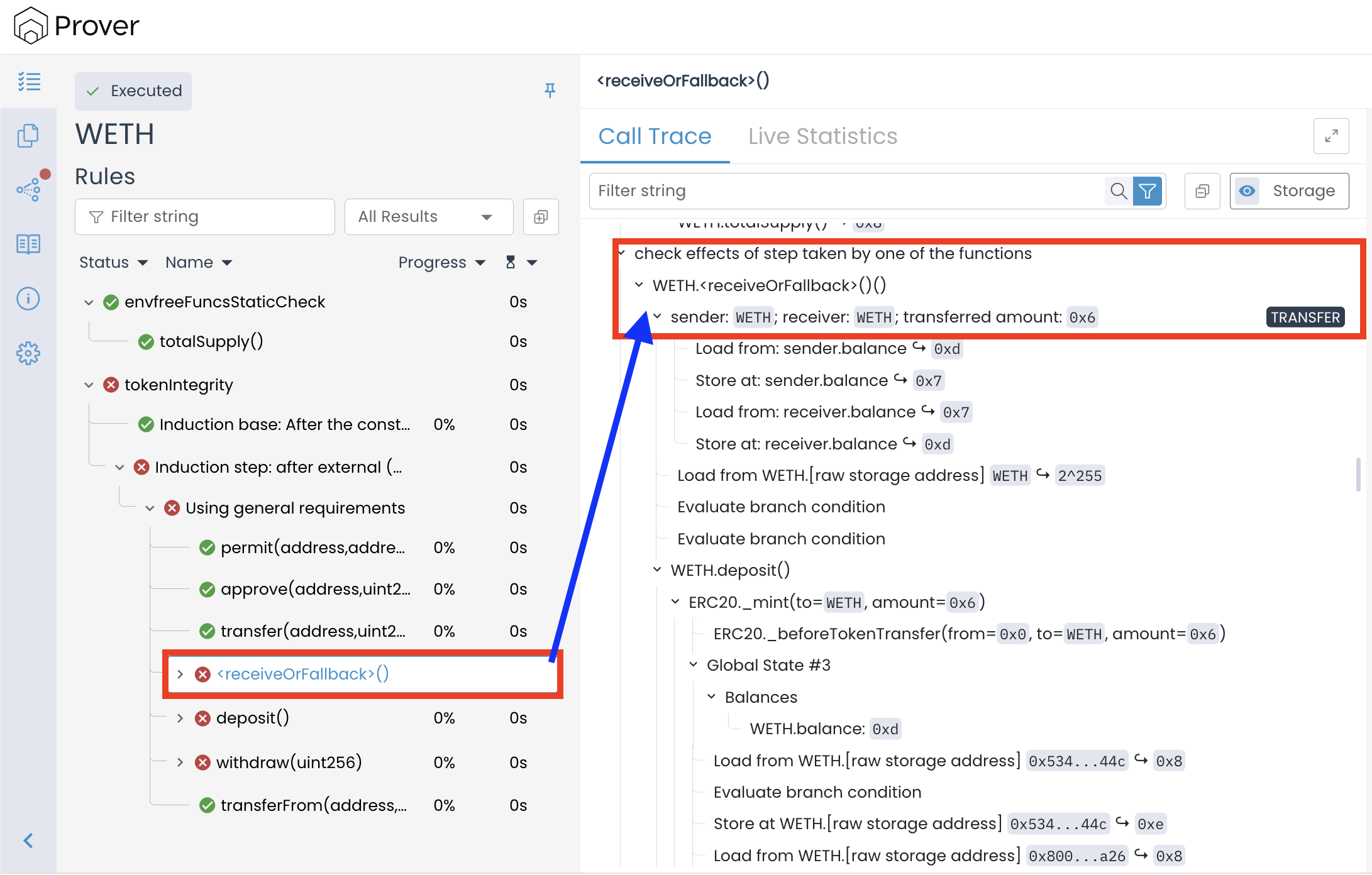

The above result of our verification run shows that the tokenIntegrity invariant failed because the Prover found a scenario where the contract’s ETH balance could be less than the reported total supply.

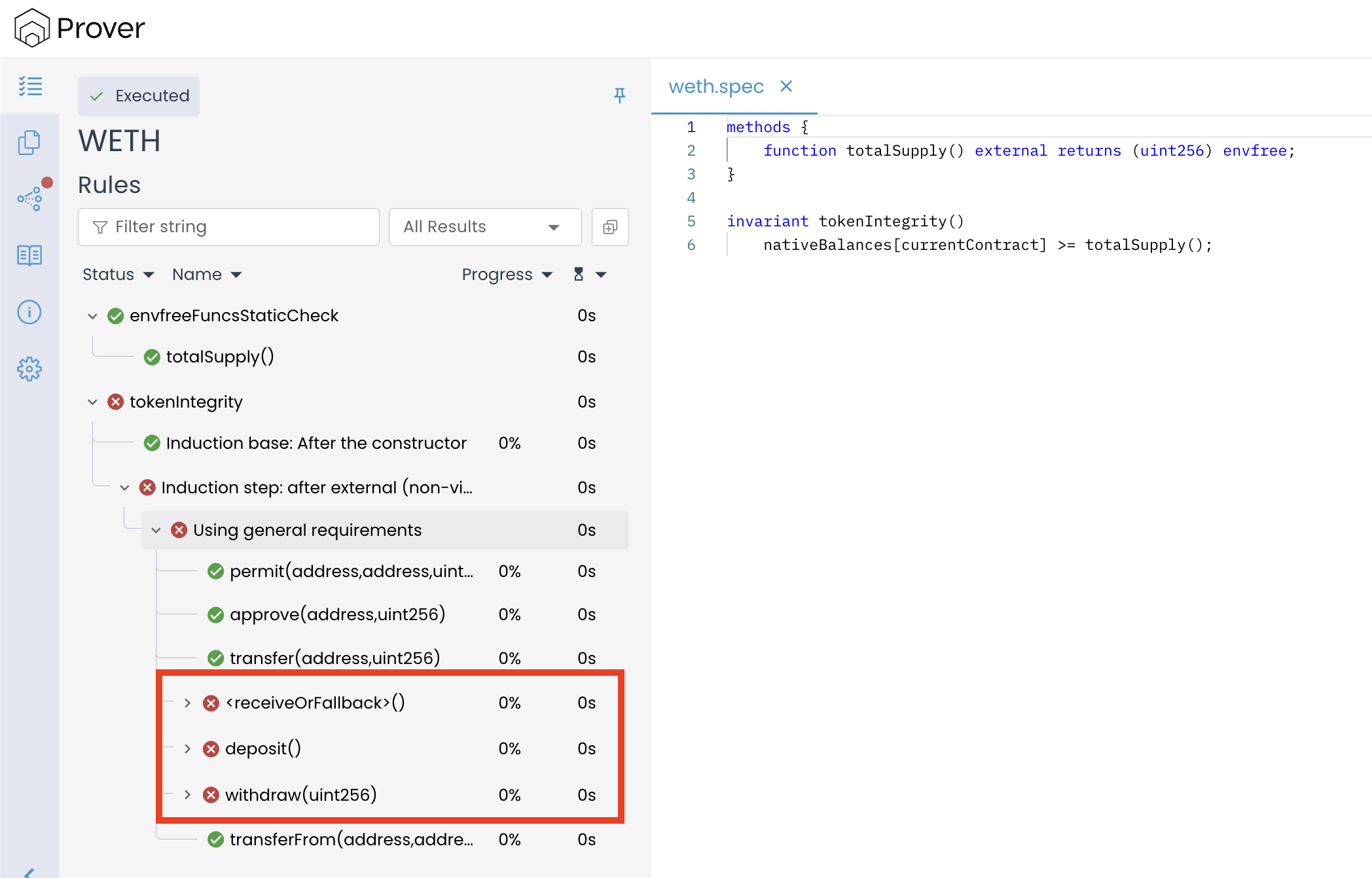

Understanding the Violation

Our detailed analysis report finds that our invariant tokenIntegrity has passed the “Induction base: After the constructor” ✅, meaning the property holds immediately after deployment. However, it failed during the “Induction step: after external (non-view/pure) method execution” ❌, which indicates that while the invariant starts off valid, it does not consistently hold after certain state-changing function calls.

To understand the cause of violation, we need to analyze the call traces of the failing functions.

Let’s begin with the deposit() function.

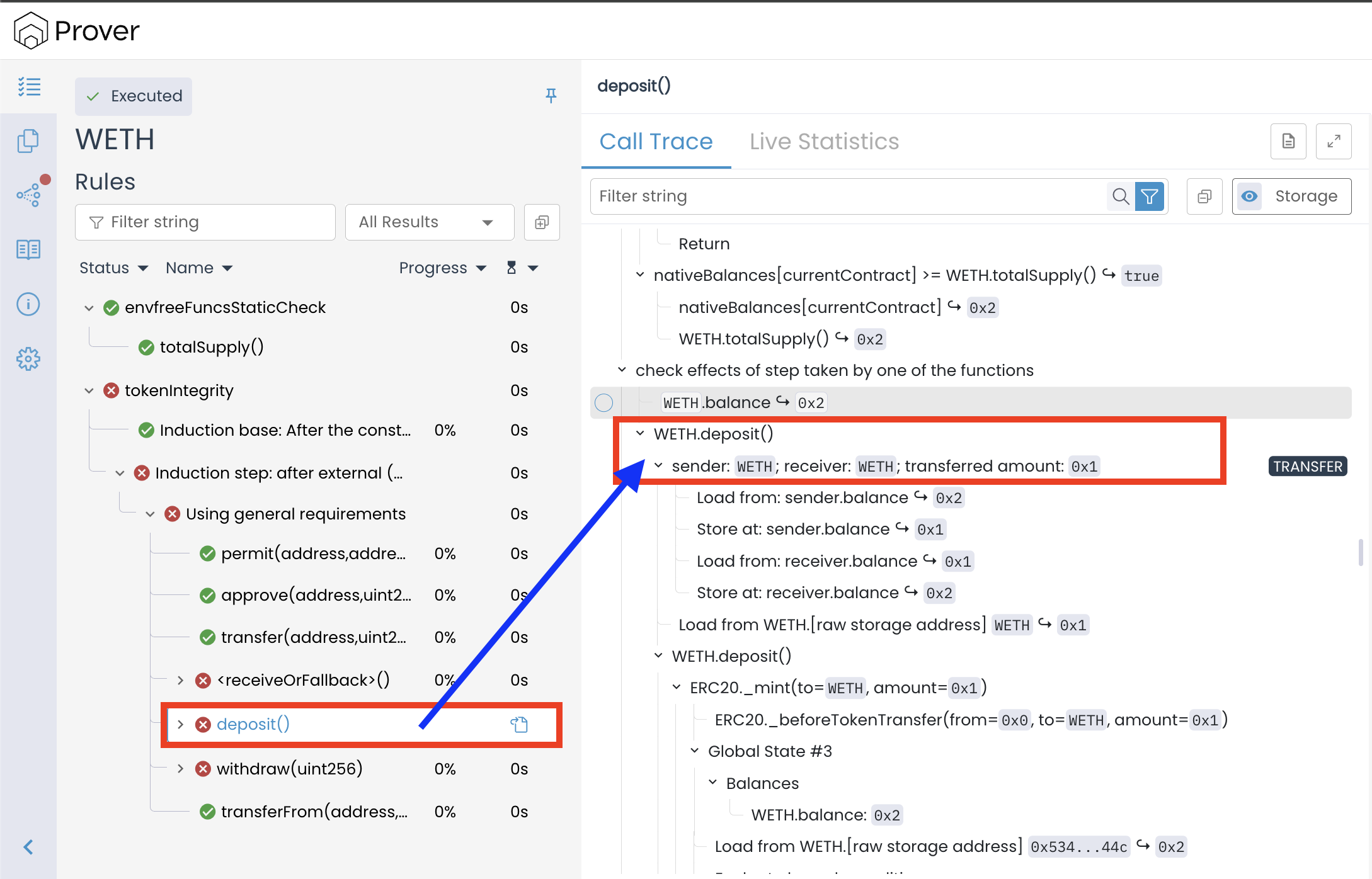

Understanding the Violation of the deposit() call

Our analysis of the call trace of the deposit() function reveals something unusual: both the sender and receiver are the contract itself (WETH).

This scenario — where the contract calls its own deposit() — is an absurd case from a practical standpoint, since the WETH contract does not contain any code path that can call deposit() directly or indirectly. While the Prover correctly identifies this as a theoretically possible interaction, we can explicitly tell it to ignore such cases through the preserved block.

Understanding the Violation of the receive() call

The receive() function in a Solidity contract is a special function that is automatically executed when the contract receives Ether with empty calldata. A contract may define only one such function, and it must have the following form:

receive() external payable { ... }

The receive() function cannot take arguments, cannot return values, and is triggered on plain ETH transfers (such as via .send, .transfer, or a raw ETH transfer).

In the WETH implementation the receive() function simply forwards calls to deposit() function:

// @dev Equivalent to `deposit()`.

receive() external payable virtual {

deposit();

}

Because of this, any unrealistic execution path that breaks deposit() can also break receive(). The Prover treats receive() as just another external entry point, so it may symbolically assume that the contract calls its own receive() function.

This is exactly what happened in the failing trace: just like with deposit(), the Prover picked a path where both the sender and receiver are the contract itself (WETH), leading to an impossible self-call scenario that does not occur in real execution but causes the invariant to fail symbolically.

Understanding the Violation of the withdraw() Call

The call trace for withdraw() reveals a problem caused by the Prover testing a wildly unrealistic scenario. To understand why it fails, let’s analyze the call trace step by step, using the exact values the Prover used.

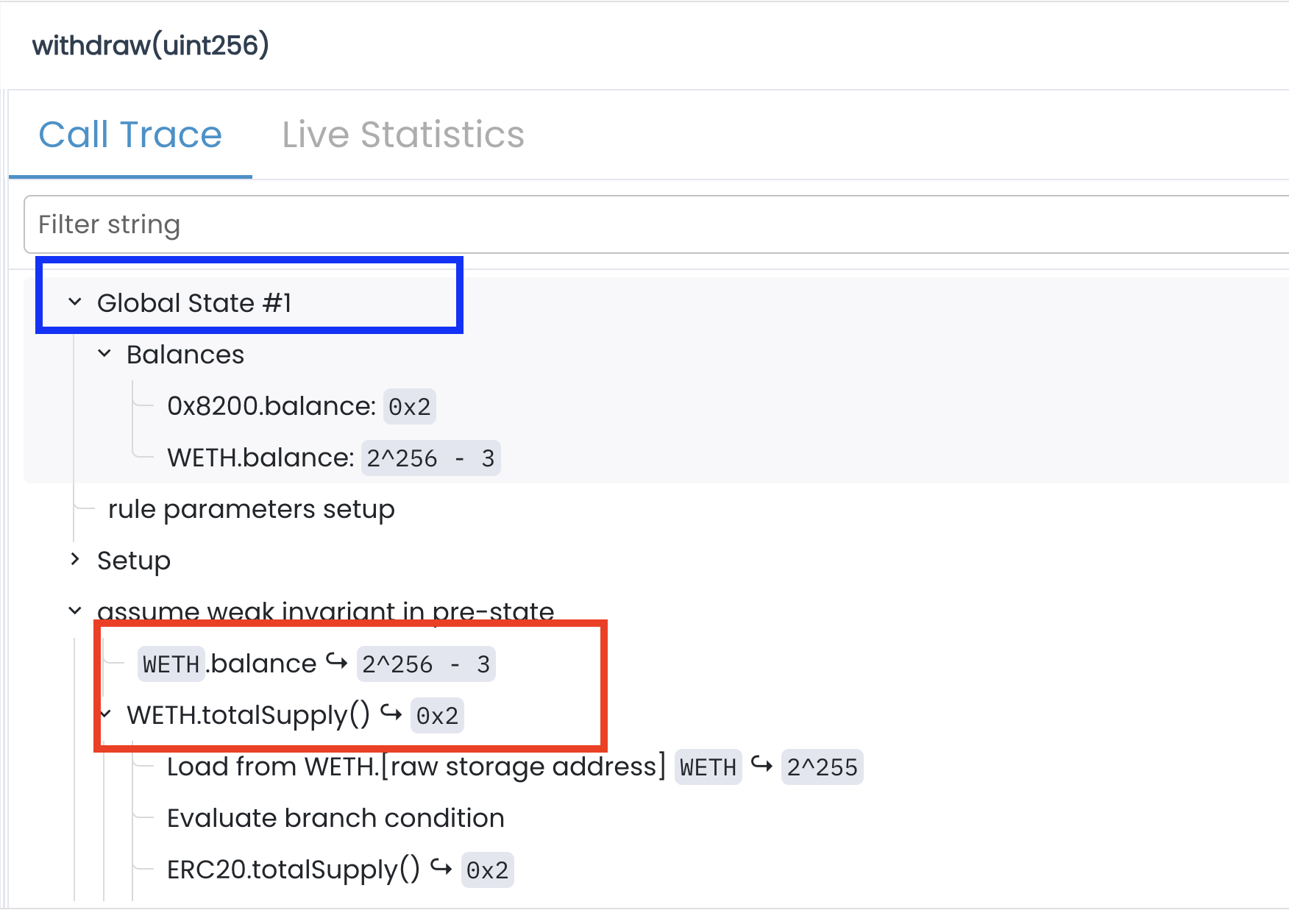

The Pre-State Check (Global State #1)

During the pre-state check, the Prover assumes that the invariant holds before the function runs. At this point—captured as Global State #1—it sets up a symbolic environment representing the possible starting conditions before the symbolic execution of the withdraw() function.

In this state, the contract’s ETH balance is set to 2^256 − 3, while the total token supply is only 2.

This means the contract begins in an impossible state—it holds a vast amount of ETH but has a total token supply of only 2. No real-world deployment could reach such a condition, but since we didn’t constrain the initial state, the Prover was free to choose arbitrary values.

At this point, our invariant holds because:

2^256 − 3 ≥ 2 ✅

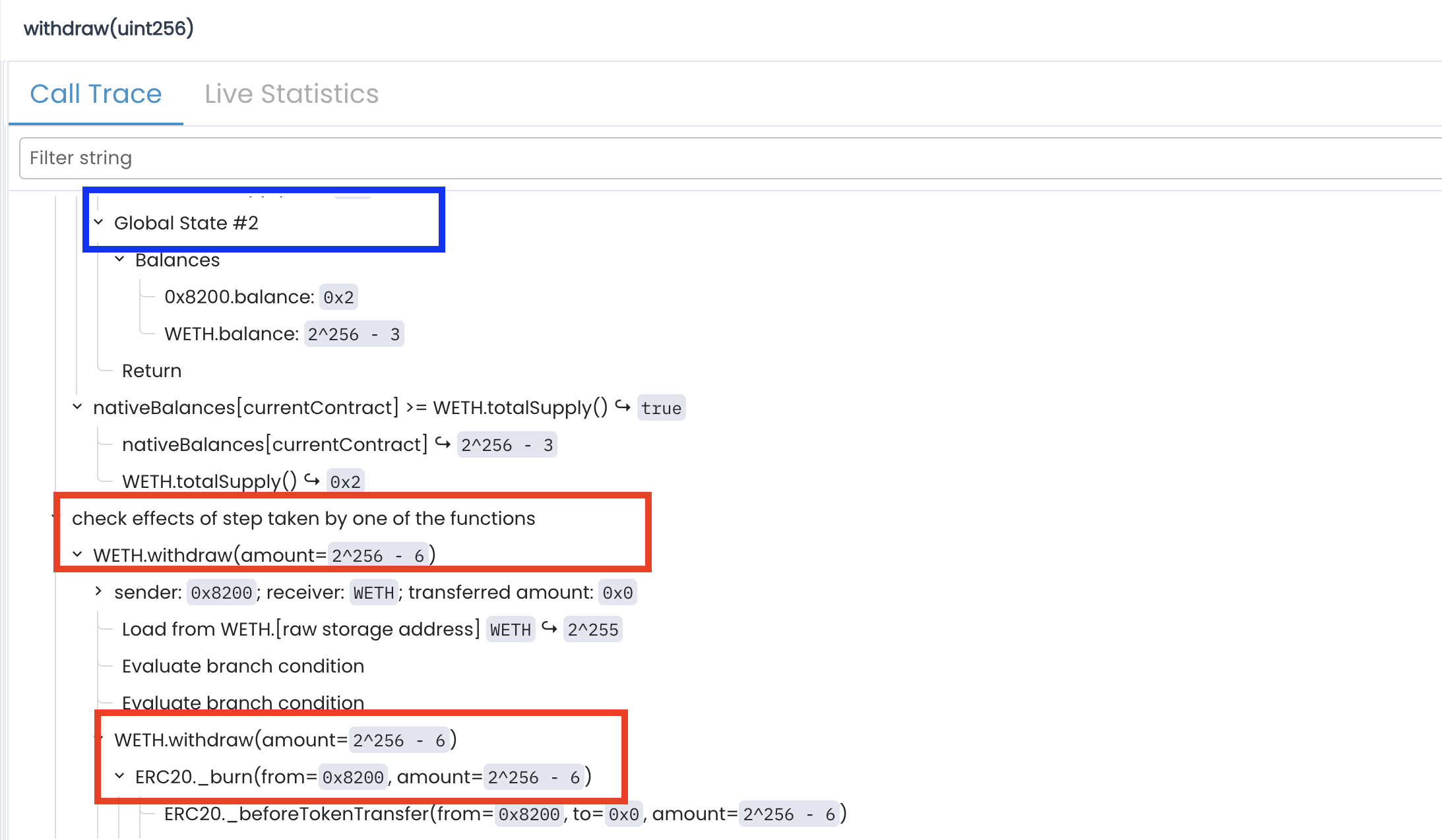

Symbolic Execution of withdraw() (Global State #2)

Next, the Prover symbolically executes the withdraw() function:

Here, the caller (0x8200) attempts to withdraw 2^256 − 6. The withdraw() function calls the internal _burn(from, amount). In a real execution, _burn() would immediately revert if amount > balanceOf(from) .

However, the Prover reasons symbolically. When it reaches the check if (amount > balanceOf(from)), it treats balanceOf(0x8200)as an unbounded symbolic variable. To explore a non-reverting path, it must assume a value for this balance that is large enough to pass the check.

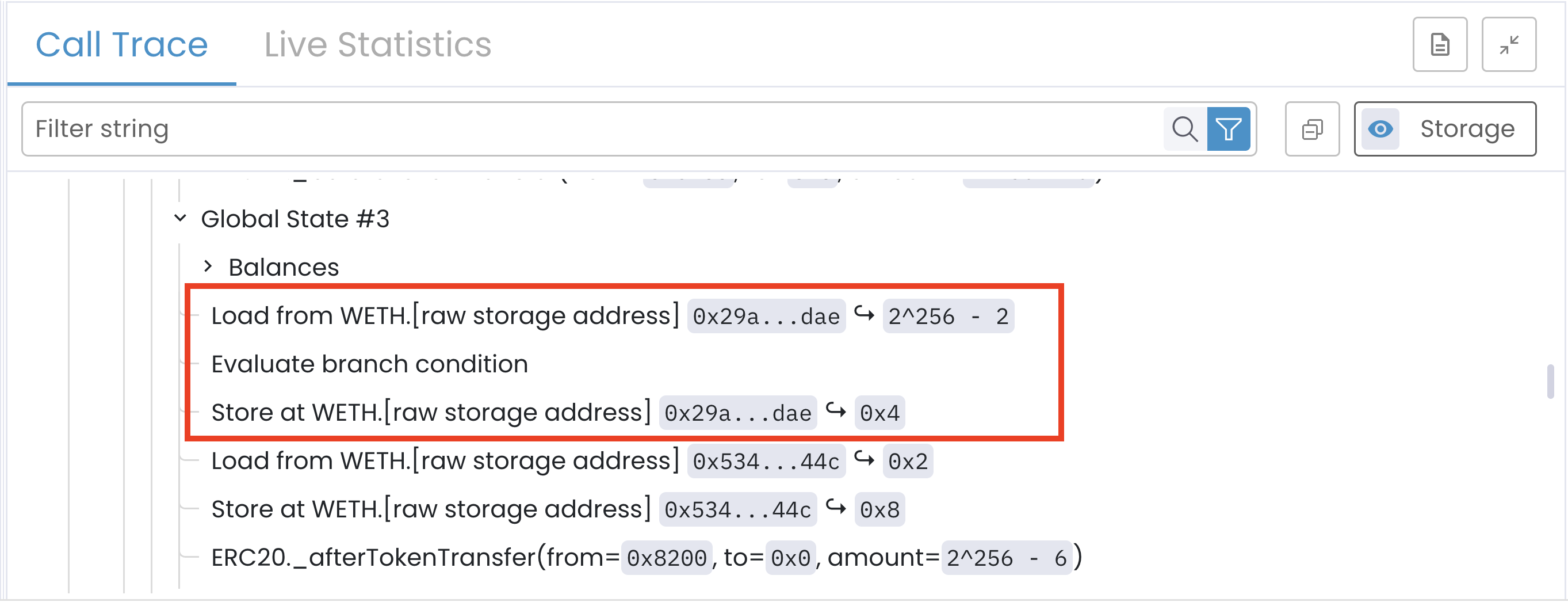

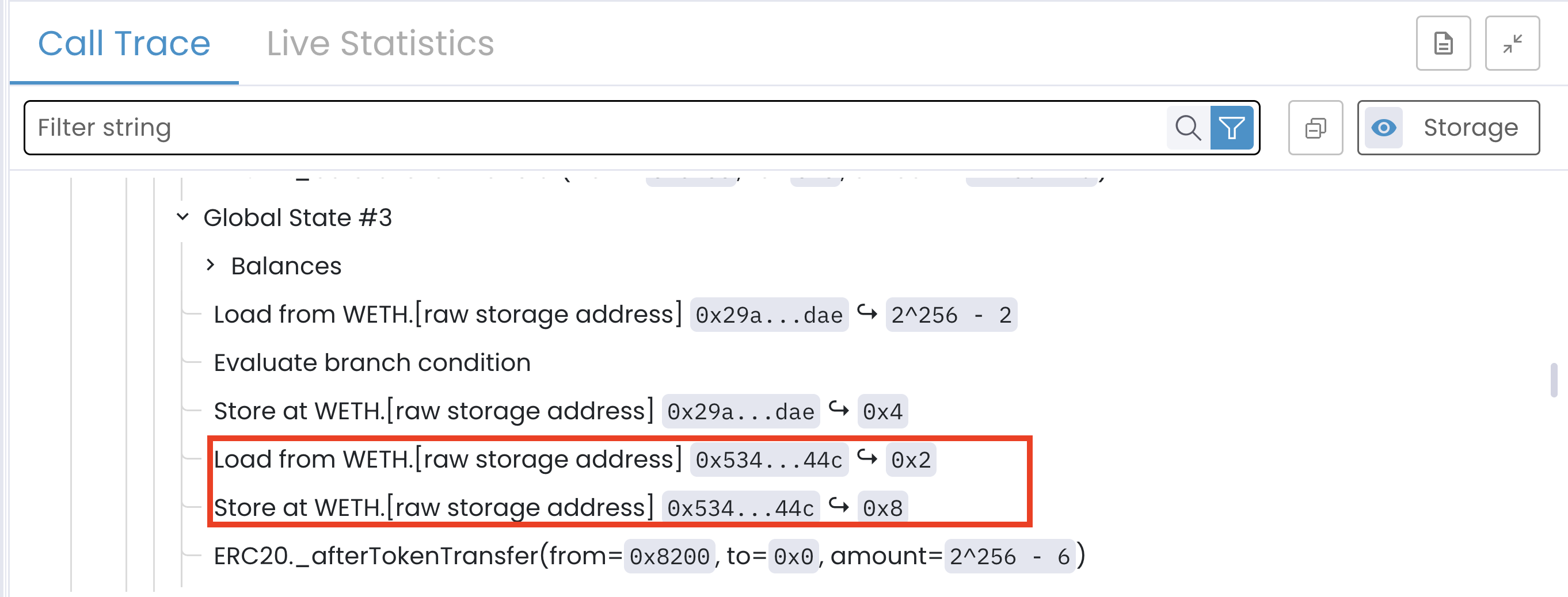

We can find this assumed value by looking at the _burn operations below Global State #3. The trace shows a classic “read-modify-write” pattern on a single storage slot (the caller’s balance):

Here’s what this tells us:

- The Prover loads the caller’s balance. To continue, it assumes the balance is

2^256 - 2. - It then stores the new balance (

0x4) after the subtraction.

We can confirm this with simple math:

Precall Balance of 0x8200 = 2^256

Withdrawal Amount = 2^256 - 6

Postcall Balance of 0x8200 should be = (2^256 - 2) - (2^256 - 6) = 4

The calculated result 4 perfectly matches the Store value 0x4.

The Arithmetic Underflow (Global State #3)

Once _burn() updates the caller’s WETH balance, it then updates the WETH total supply.

At this point, totalSupply changes from 2 to 8 because 2 − (2^256 − 6) underflows uint256 and wraps modulo 2^256.

Note: In Solidity versions ≥0.8.0, normal arithmetic such as totalSupply -= amount would revert on underflow. However, this does not happen when the contract uses an unchecked block or performs the operation in inline assembly, since both follow low-level arithmetic semantics where values wrap around modulo 2^256.

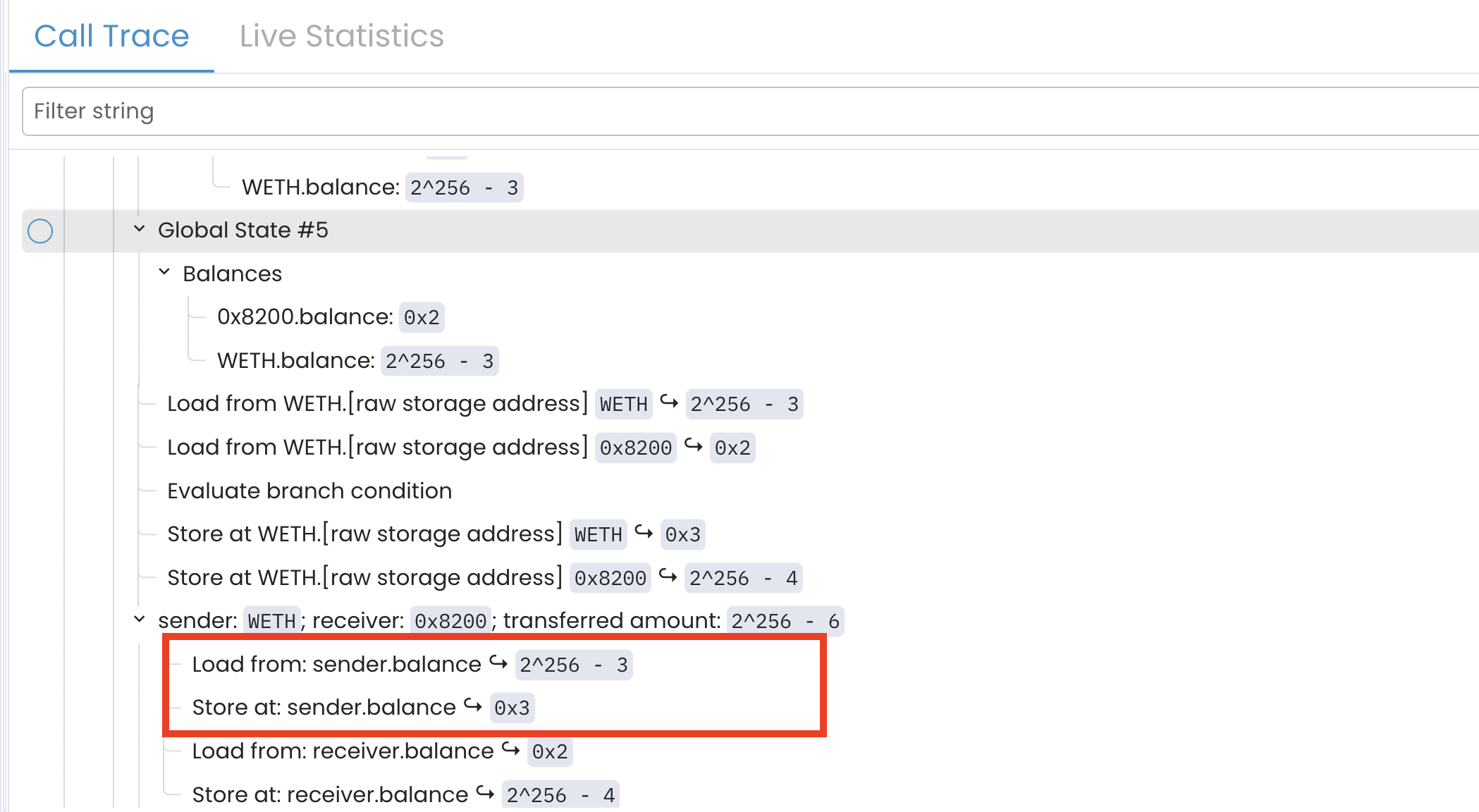

The Unresolved ETH Transfer and AUTO-Havoc (Global State #5)

After _burn() completes, withdraw() attempts to transfer the ETH to the caller using a low-level call:

call(gas(), caller(), amount, codesize(), 0x00, codesize(), 0x00)

Before the call to withdraw(), the WETH contract held 2^256 − 3 wei. A successful call to withdraw() will result in the transfer of 2^256 − 6 wei to the caller and should decrease the contract’s ETH balance from 2^256 − 3 down to 3.

If we look at the trace for Global State #5, we see the Prover does this calculation correctly at first:

However, the Prover doesn’t stop there. The call is to an external, unknown address (the caller()). The Prover cannot determine this callee’s behavior (i.e., the caller’s fallback function).

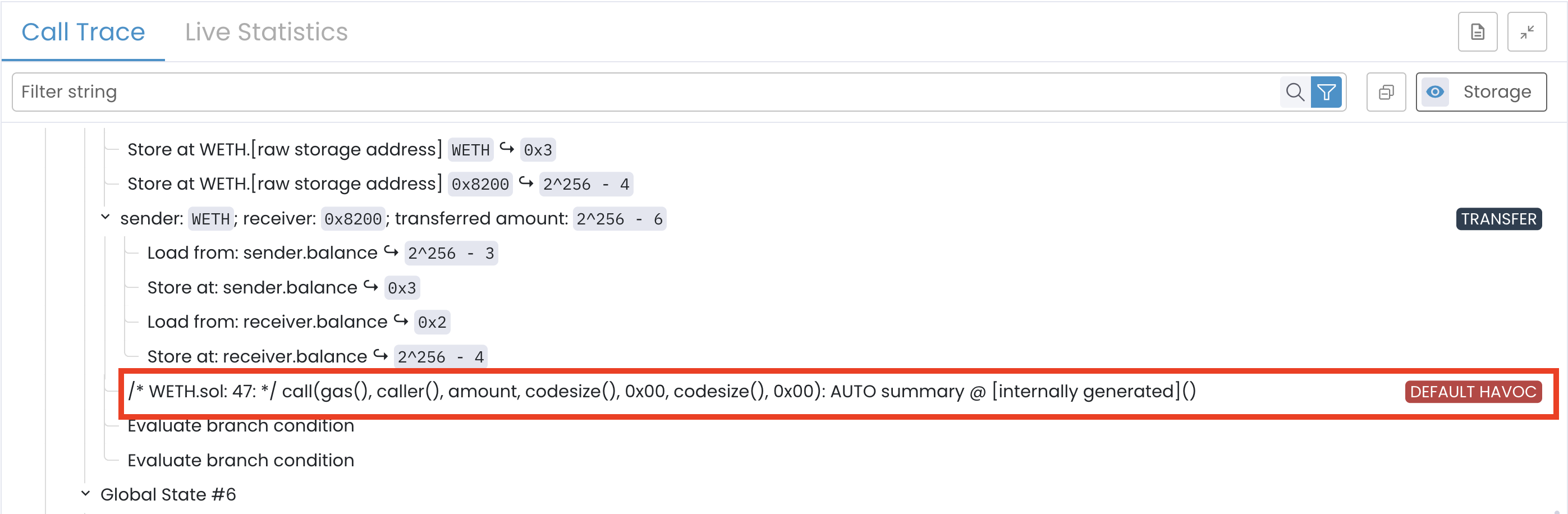

When the Prover faces such unresolved external calls, it automatically applies an AUTO-havoc summary.

Under AUTO-havoc, the Prover assumes the external call succeeds but may arbitrarily modify state variables related to the call. It does this because it lacks a concrete model of the callee’s code.

In the call trace, we see this happen immediately after the correct calculation:

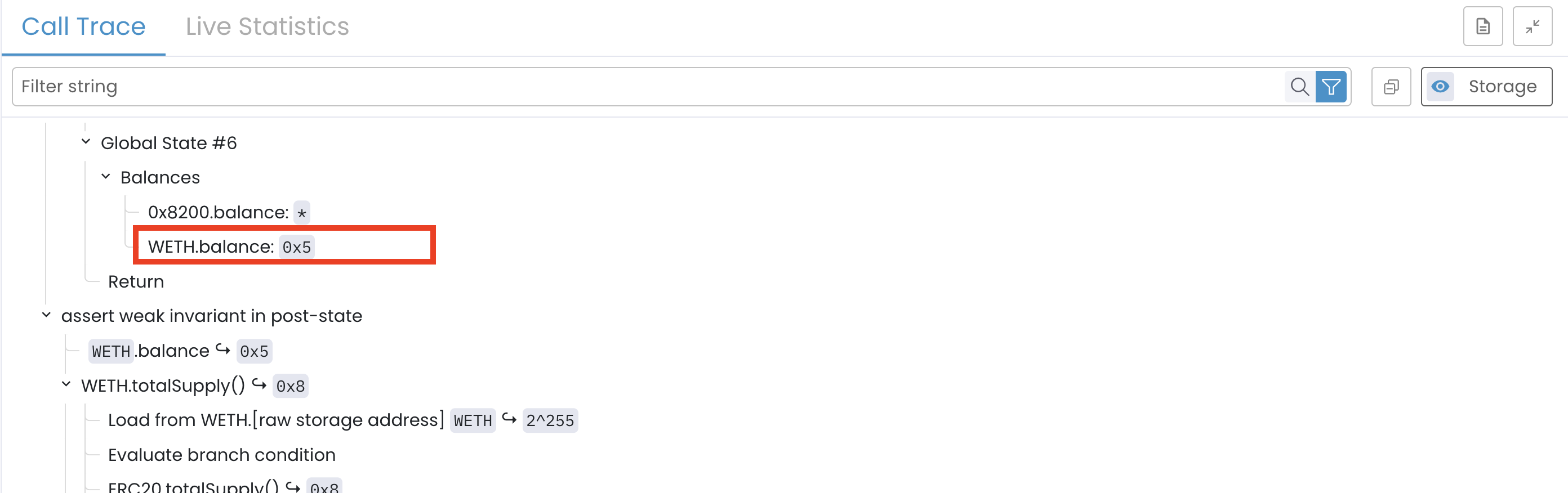

This havoc overwrites the computed balance. In the next state (Global State #6), the contract’s balance is:

This means the Prover ignored the computed result (3) and assigned an arbitrary value (5) as part of the havoc summary. This havoc’d value is what will be used in the post-state check.

The Post-State and Invariant Failure (Global State #7)

After the withdraw function completes, the Prover checks the invariant in the post-state:

nativeBalances[currentContract] >= totalSupply()

At this point, the symbolic values are:

WETH.balance = 0x5(Set by AUTO-havoc)WETH.totalSupply() = 0x8(Corrupted by the underflow)

So the invariant evaluates to:

5 >= 8 ❌ (false)

The Prover concludes that the invariant was violated.

The Root Cause

This violation is a classic false positive. It did not occur because of a logical flaw in the WETH contract’s withdraw() implementation. Instead, it resulted from the Prover’s under-constrained symbolic reasoning:

- The entire execution path was only possible because the Prover assumed an impossible pre-state where

balanceOf(msg.sender)was (2^256 - 2) drastically larger thantotalSupply(2). - This unrealistic assumption, allowed by an unconstrained symbolic variable, directly triggered an arithmetic underflow in the

totalSupplyvariable, corrupting it from 2 to 8.

The auto``-havoc step also contributed to the final values, but the state was already irrecoverably affected by the underflow.

Fixing False Violations Using Preserved Blocks

Now that it is clear the Prover flagged violations not because of a flaw in the WETH contract, but because it explored symbolic states that can never occur in real execution, our next step is to guide the Prover back toward realistic behavior.

We do this by adding preserved blocks, which introduce additional assumptions between the pre-state check and symbolic execution. These assumptions prevent the Prover from entering impossible execution paths such as contract self-invocations or absurd token balances.

Fixing the deposit() and receive() Violation

Both violations were caused by the Prover assuming self-calls, where the WETH contract was modeled as its own caller. This is impossible in real execution but valid in symbolic execution unless restricted.

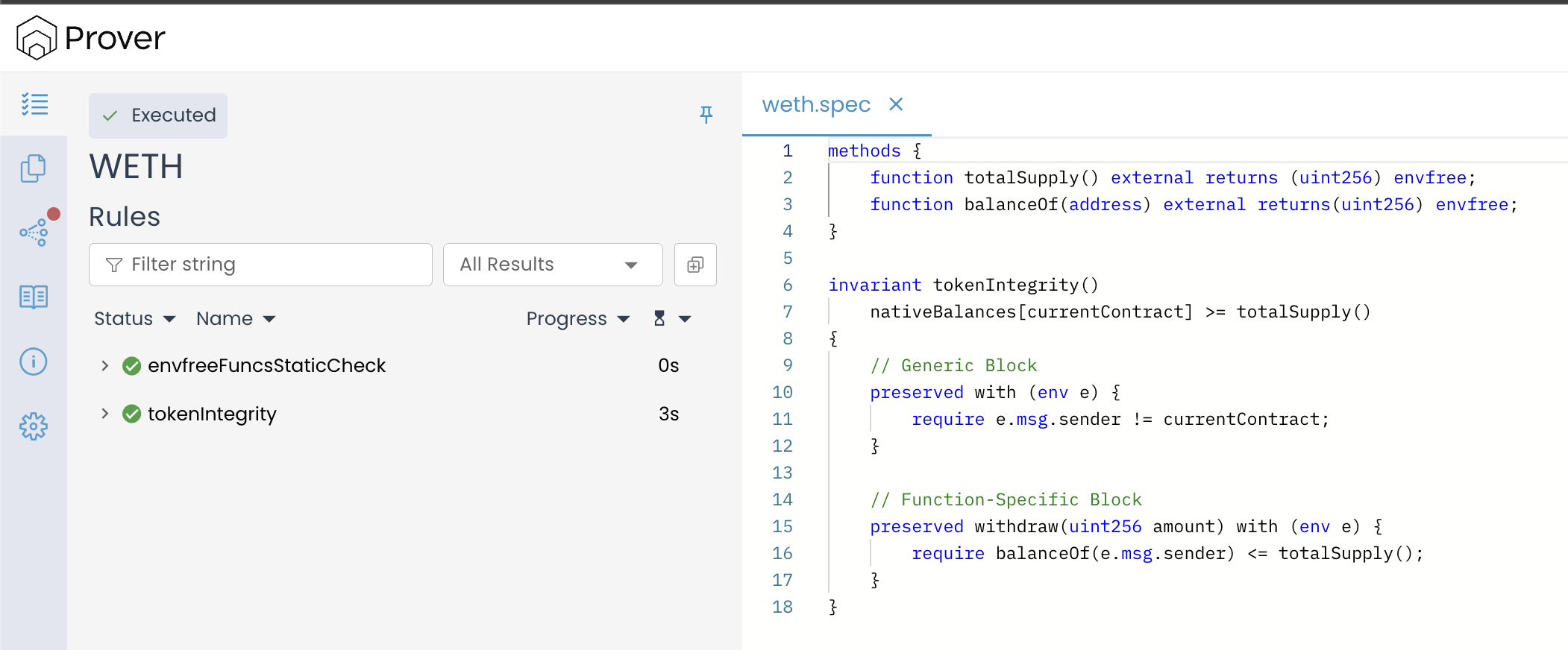

We fix this by adding a preserved block that rules out any scenario where the contract calls its own functions:

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns (uint256) envfree;

}

invariant tokenIntegrity()

nativeBalances[currentContract] >= totalSupply()

{

preserved with(env e) {

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

}

}

This single assumption removes all self-call traces, immediately eliminating the false positives in both deposit() and receive() (reported as receiveOrFallback() in the Prover UI).

With the self-call issue resolved for both deposit() and receive(), we can now turn to the second source of false violations: the unrealistic symbolic assumptions inside withdraw().

Fixing the withdraw() Violation

The failure in withdraw() was caused by something different: the Prover assumed that balanceOf(msg.sender) could be arbitrarily large, even greater than the total supply. This forced _burn() to execute along a path that should revert, triggering an underflow and corrupting totalSupply.

To prevent this, we add a preserved block specifically for withdraw():

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns (uint256) envfree;

//we also added the signature of balanceOf()

function balanceOf(address) external returns(uint256) envfree;

}

invariant tokenIntegrity()

nativeBalances[currentContract] >= totalSupply()

{

// Generic Block

preserved with (env e) {

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

}

// Function-Specific Block

preserved withdraw(uint256 amount) with (env e) {

require balanceOf(e.msg.sender) <= totalSupply();

}

}

In the above updated spec, the line require balanceOf(e.msg.sender) <= totalSupply(); instructs the Prover to ignore any execution path where a user’s token balance exceeds the total supply

Together, these preserved blocks eliminate every unrealistic execution path that previously caused a false violation. With these constraints in place, we can now re-run the Prover to check whether the invariant holds under realistic assumptions.

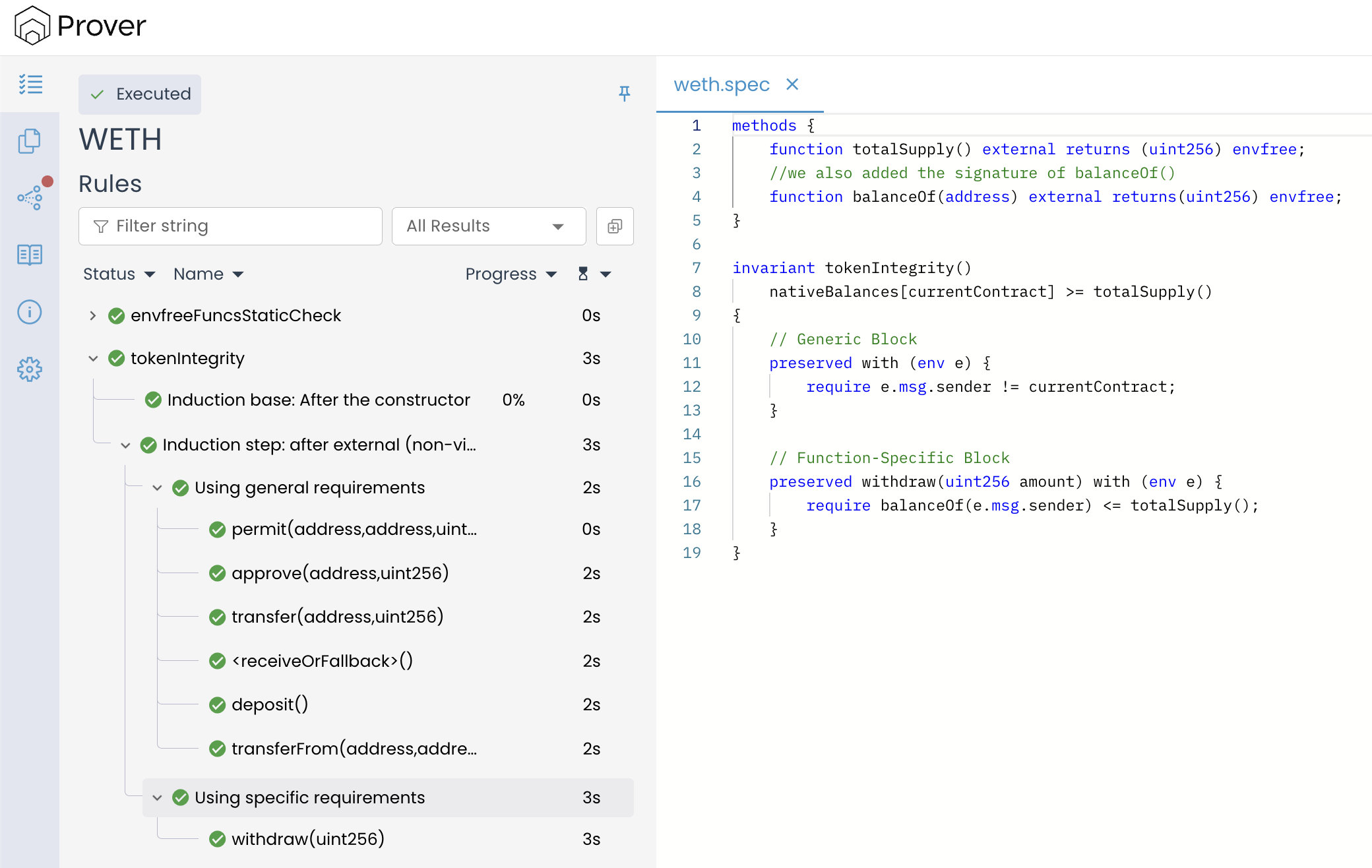

Re-running the Verification

After applying both fixes, run the Prover again and open the verification result link to view an output similar to the image shown below.

This time, the Prover confirms that the tokenIntegrity invariant holds across all verification phases, passing both the induction base and the induction step.

The report shows that all relevant functions — including deposit(), withdraw(), transfer(), and approve() — now preserve the invariant.

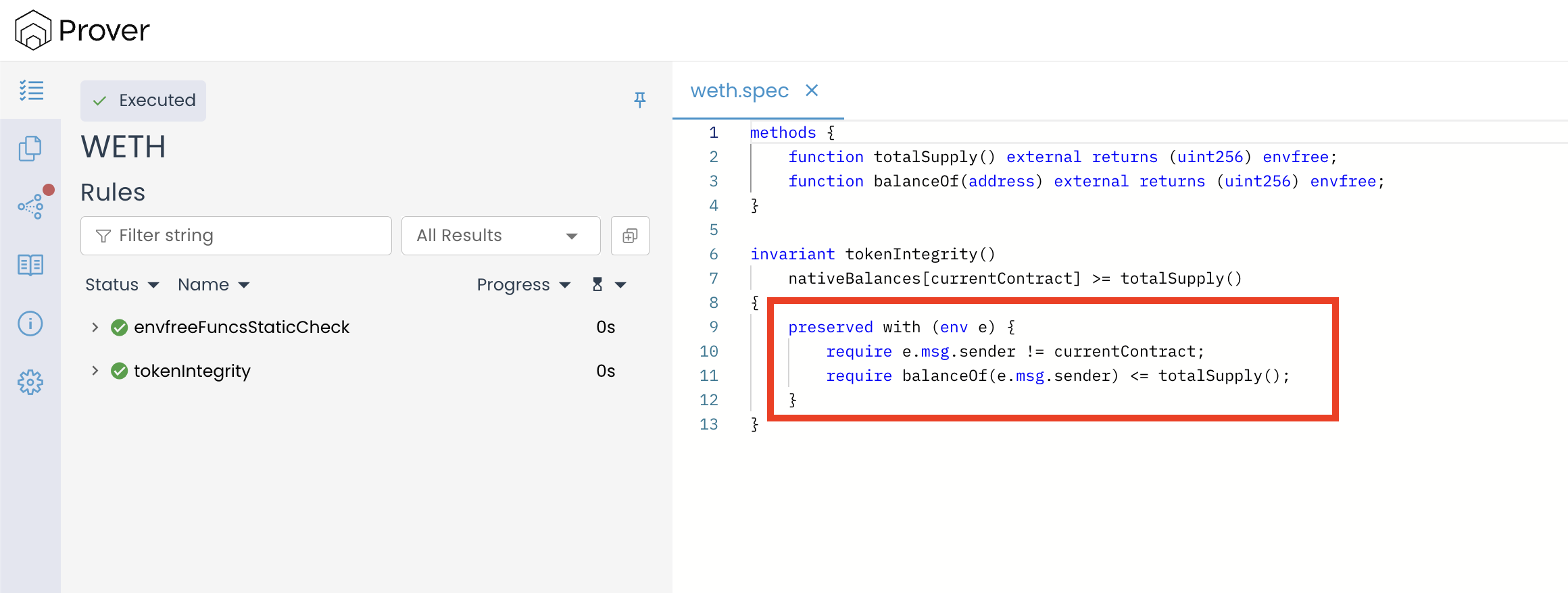

At this point, the invariant is verified successfully, and the specification is correct. However, we can simplify it further. Both assumptions we added earlier share the same structure and do not depend on any function arguments, which means we can consolidate them into a single, cleaner preserved block.

A Cleaner and More Unified Specification

In our case, both assumptions we added earlier share an important property:

“They depend only on the transaction environment (env) and the contract’s global state. They do not depend on the parameters of any particular function.”

This means they are global truths about the contract:

- The contract is never its own caller.

- A caller’s balance never exceeds the total supply.

Since neither condition depends on a function’s arguments, both can safely be placed into a single generic preserved block, as shown below:

methods {

function totalSupply() external returns (uint256) envfree;

function balanceOf(address) external returns (uint256) envfree;

}

invariant tokenIntegrity()

nativeBalances[currentContract] >= totalSupply()

{

preserved with (env e) {

require e.msg.sender != currentContract;

require balanceOf(e.msg.sender) <= totalSupply();

}

}

When we run the Prover using this combined block, the specification is accepted without errors and the invariant holds across all verification phases, as shown in the image below:

Constructor Preserved Blocks (Base-Step Assumptions)

So far, we have discussed preserved blocks as a way to constrain the Prover during the induction step of invariant verification—that is, when checking that public and external functions preserve an invariant assuming it already holds beforehand.

Starting with Prover version 8.5.1, CVL also supports constructor preserved blocks, which apply to the base step of invariant verification.

During the base step, the Prover symbolically executes the constructor to verify that the invariant holds immediately after deployment. The main contract’s storage (currentContract) is initialized to zero, but in multi-contract scenes, other contracts in the verification scene start in arbitrary symbolic states.

This is a change from earlier Prover versions, where the storage of all contracts was assumed to be zeroed—corresponding to freshly deploying the entire system at once. The current behavior enables more realistic modeling of deployed systems, but it also means that base-step verification may start from states that would never arise in an actual deployment.

When an invariant depends on relationships with these external contracts, the symbolic environment may violate assumptions that would hold in practice, causing the base step to fail for purely symbolic reasons. Constructor preserved blocks allow us to reintroduce these assumptions explicitly, ensuring that the base step reflects a realistic deployment context.

The syntax mirrors that of other preserved blocks but is scoped to the constructor:

preserved constructor() with (env e) {

require e.block.timestamp != 0;

}

This block applies only to the base step and has no effect on the induction step or on individual function verification.

In this chapter, the false violations in the WETH case study arise during the induction step, so they are resolved using generic and function-level preserved blocks. Constructor preserved blocks are most useful when an invariant fails immediately after deployment due to unrealistic assumptions about the initial symbolic environment.

Conclusion

Preserved blocks are a powerful tool for refining invariant verification in CVL. By constraining the Prover to realistic assumptions—both during function execution and, when necessary, during deployment—they eliminate false positives while preserving the strength of the proof.

Through the WETH case study, we saw how carefully chosen preserved blocks can guide the Prover away from impossible symbolic states and toward meaningful executions, ensuring that invariants are verified under conditions that accurately reflect real-world behavior.