This article describes how elliptic curve addition works over real numbers.

Cryptography uses elliptic curves over finite fields, but elliptic curves are easier to conceptualize in a real Cartesian plane. This article is aimed at programmers and tries to strike a balance between getting too math heavy and too hand-wavy.

Set theoretic definition of elliptic curves

The set of points on an elliptic curve form a group under elliptic curve point addition.

Hopefully, if you’ve been following our group theory introduction, then you actually understood most of this, aside from what “point addition” is. But that’s the beauty of abstract algebra right? You don’t need to know what that is, and you still understand the above sentence.

Elliptic curves are a family of curves which have the formula

Depending on what value of a and b you pick, you’ll get a curve that looks like some of the following:

A point on an elliptic curve is an pair that satisfies for a given and .

For example, the point is in the curve because it . In group theoretic terms, is a member of the set defined by . Since we are dealing with real numbers, the set has infinite cardinality.

The idea here is we can take two points from this set, do a binary operator, and we will get another point that is also in the set. That is, it is an pair that also lies on the curve.

Instead of thinking about elliptic curves as a plot on a graph, think of them as an infinite set of points. Points are in the set if and only if they satisfy the elliptic curve equation.

Once we see these points as a set, looking at them as a group isn’t mysterious. We just take two points, and produce a third according to the rules of a group.

Specifically, to be a group, the set of points needs to have:

- a binary operator that is closed and associative, i.e. it produces another point in the set

- the set must have an identity element

- every point in the set must have an inverse such that when the two are combined with the binary operator, the result is

Elliptic Curves form an abelian group under addition

Although we don’t know how the binary operator works, we do know that it takes two points on the curve and returns another point on the curve. Because the operator is closed, we know that the point will in fact be a valid solution to the elliptic curve equation, not a point somewhere else.

We also know that this binary operator is associative (and commutative, per the section heading).

So given three points on the elliptic curve , , and (or , , and if you prefer), we know the following is true:

I’m using , because we know this binary operator is not addition in any normal sense, but a binary operator (again, remember from set theory, a binary operator takes two elements in a set and returns another element in a set, how it does that is not central to the definition).

We also know that there has to be an identity element somewhere. That is, any point that falls on the curve is combined with the identity element, the output is the same point unchanged.

And because this is a group and not a monoid, every point needs to have an inverse such that , where is the identity element.

The identity element

Intuitively, we might think of or being the identity element, since something like that often is in other groups, but you can see in the plots above that those points generally do not land on the curve. Since they don’t belong to the set of points on , they are not part of the group.

But recall from set theory that we can define binary operators however we like over sets arbitrarily defined. This allows us to add a special element that isn’t technically on the curve but by definition is the identity element.

I like to think of the identity element as “the point that is nowhere” because if you combine nowhere with any real point, nothing changes. Annoyingly, mathematicians call this point, the identity element “the point at infinity.”

Hey wait, isn’t this point supposed to satisfy ? Nowhere (or infinity) is not a valid value for .

Ahh, but remember, we can define sets however we like! We define the set that makes up the elliptic curve as points on the elliptic curve and the nowhere point.

Because binary operators are just subsets of a cartesian product (a relation), and we can define the relation however we like. We can have as many hacky “if statements” in our arithmetic as we please and still follow the group laws.

Addition is closed.

Without loss of generality, let’s take the elliptic curve

To illustrate how lines intersect on elliptic curves, then let’s draw a nearly vertical line

(It could be 1000x to make it more vertical, but we would get numerical instability as you will see later)

We get the following set of plots.

It turns out, even though it looks like the purple line () is rising faster than the blue curve (), they will always eventually intersect.

If we zoom out far enough, we can see the intersection. This is true in general.

As long as x is not “perfectly vertical” if it crosses two points on the curve, it will always cross a third. Two of those points could be the same point if one of the points of intersection is a tangent point.

The “if we intersect two points” is important. If we shift our purple line over to the left so it doesn’t cross the “U-turn” of the elliptic curve, then it will only cross at one point

Another way of understanding it:

If a straight line crosses an elliptic curve at exactly two points, and neither of the intersection points are tangent intersections, then it must be perfectly vertical.

You could work out an algebraic proof from the formulas above, but I think the geometric argument is more intuitive.

I recommend you stop here and draw some elliptic curves and lines and convince yourself of this visually.

Our exception for vertical lines actually causes inverse and identity elements to fall into place beautifully.

The inverse of an elliptic curve point is the negative of the y value of the pair. That is, the inverse of is and vice versa. Drawing a line through such points creates a perfectly vertical line.

The identity element is the “point at infinity” we alluded to earlier is simply the point “way up there” when we draw a vertical line.

Abelian Group

The fact that elliptic curve points are a group under our “2 points always result in a 3rd except for the identity” makes its commutative nature obvious.

When we pick two points, there is only one other third point. You can’t get four intersections in an elliptic curve. Since we only have one possible solution, then it is clear that .

Why elliptic curve addition flips over the x axis

We glossed over a very important detail in the last section, because it really deserves a section on its own.

In it’s current form, it has a bug if we add two points where the intersection happens in the middle.

Using our definitions above, the following must be true

With a little algebra, we’ll derive a contradiction

This says is equal to it’s inverse. But is not the identity element (which is the only element that can be the inverse of itself), so we have a contradiction.

Thankfully, there is a way to rescue this. Just define point addition to be the third point flipped over the y axis. Again, we are allowed to do this because binary operators can be defined however we like, we just care that our definitions satisfy the group laws.

So the correct way to add elliptic curve points is represented graphically below

Formula for Addition

Using some algebra, and given two points

One can derive how to compute where using the following formula.

Algebraically demonstrating commutativity and associativity

Because we have a closed form equation, we can prove algebraically that given points and .

We do it as follows

var('y_t', 'y_u', 'x_t', 'x_u')

lambda_p = (y_u - y_t)/(x_u - x_t)

x_p = lambda_p^2 - x_t - x_u

y_p = (lambda_p*(x_t - x_p) - y_t)

lambda_q = (y_t - y_u)/(x_t - x_u)

x_q = lambda_q^2 - x_u - x_t

y_q = (lambda_q*(x_u - x_q) - y_u)

Here is a screenshot of running the above code in Jupyter notebook and pretty printing the output. The computer algebra system needs a bit of coaxing, but we can clearly see x_q == x_p and y_q == y_p.

for all and values. We get a division by zero error if , but this means they are the same point and that is obviously commutative.

We can use similar techniques to demonstrate associativity, but unfortunately this is extremely messy so we refer the interested reader to another proof of associativity.

Elliptic curves meet the abelian group property

Let’s see that elliptic curves meet the group property.

- The binary operator is closed. It either intersects with a 3rd point on the curve or the point at infinity (identity). We are guaranteed to get a third valid point when we intersect two points. The binary operator is associative.

- The group has an identity element.

- Each point has an inverse.

- The group is abelian because A ⊕ B = B ⊕ A

A binary operator must accept every possible pair from the set. What if the pair is the same element, i.e. A ⊕ A?

Point multiplication: adding a point with itself

Let’s think of this in limit terms. Adding a point to itself is like bringing two points infinitesimally close to each other until they become the same point. When this convergence happens, the slope of the line will lie tangent to the curve.

So adding a point to itself is simply taking the derivative at that point, getting the intersection, then flipping the axis.

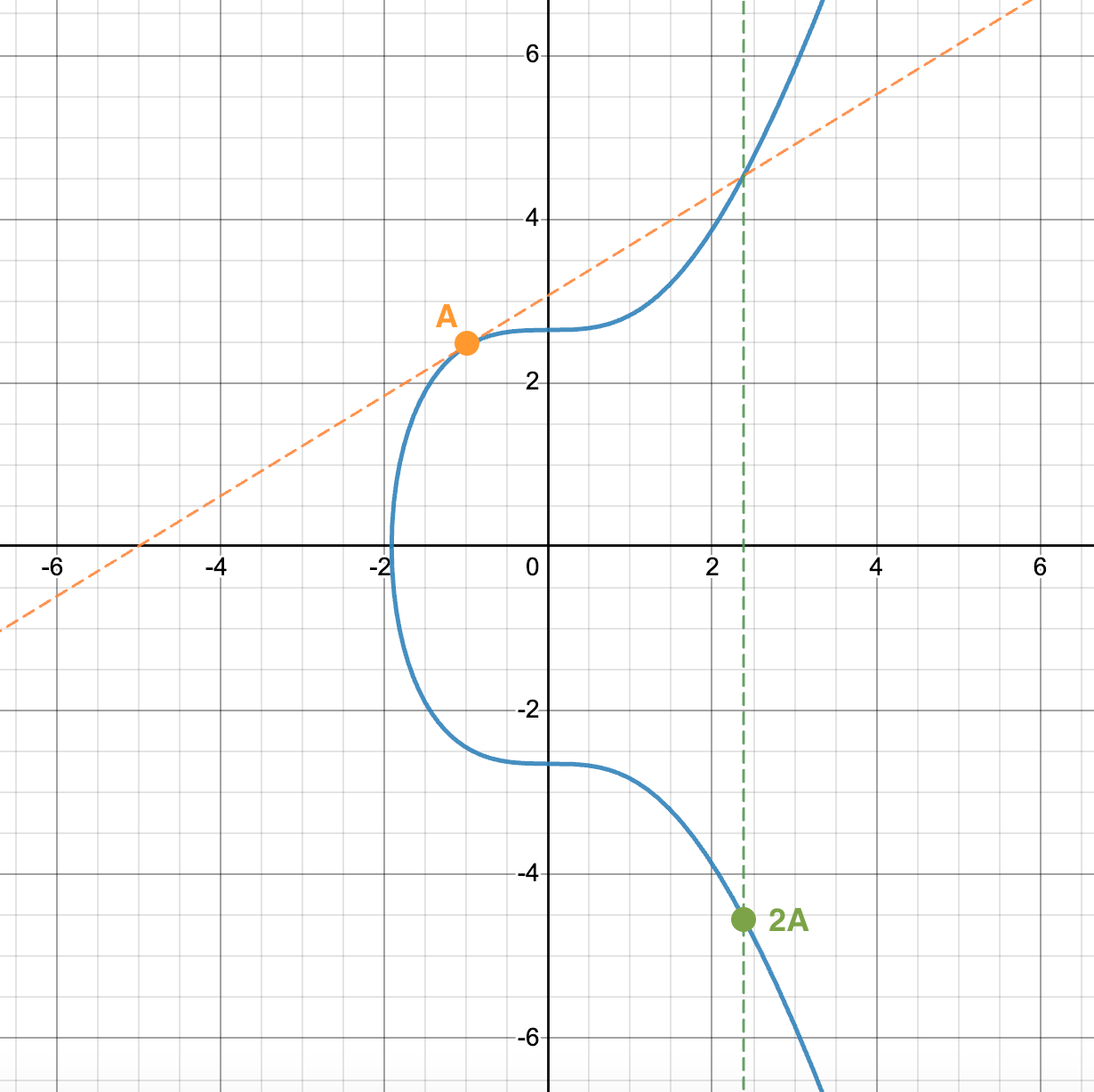

The following image graphically demonstrates .

Shortcut for point multiplication

What if we wanted to compute instead of ? It would seem this is an operation, but it isn’t.

Because of associativity, we can write as

(and the other terms) can be computed quickly because 512 is just doubled 9 times.

So rather than doing 1000 operations, we can do it in 14 (9 to compute 512, caching the intermediate results, then 5 additions).

This is actually an important property when we get to cryptography:

We can efficiently multiply an elliptic curve point by a large integer.

Implementation details of addition

It isn’t too hard to derive the formula for point addition using simple algebra. When we intersect two points, we know the slope and the points that it crossed through, so we can calculate the point of intersection.

I’d rather not do that here because I don’t want to get lost in a bunch of symbolic manipulation.

The whole power of group theory is that we don’t care what that symbolic manipulation looks like. We know that if we do our binary operator on two points, we’ll get another point in our set, and our set follows the group laws.

If you think about it that way, elliptic curves are much easier to understand.

Rather than trying to understand elliptic curves in isolation from the ground up, we study a bunch of other algebraic groups, then transfer that knowledge and intuition to elliptic curves.

Rational numbers under addition are a group. Integers modulo a prime are a group under multiplication. Matrices of non-zero determinant under multiplication are a group.

You do the binary operator, and you get another item in the set. The group has an identity element, and each element has an inverse. Associative law holds. With all that in mind, you shouldn’t care what the operator ⊕ is doing behind the scenes.

In my opinion, if you try to understand elliptic curves math in isolation from first principles of group theory, you’re doing it the hard way. It’s far easier to understand it in the context of its relatives.

That makes for a smoother learning experience.

Algebraic manipulation is really just associative addition.

Let be an elliptic curve point. What happens we do something like this?

At first, it may seem weird that we can do that, because if we try to visualize what is happening with the elliptic curve, we will surely get lost.

Remember, what looks like multiplication above is really just a point getting added with itself repeatedly, so this is what actually happens under the hood when looking at it as a group

Scalar “multiplication” isn’t “distributive” the way we would think about normal algebra. It’s just shorthand for rearranging the order in which we add P to itself.

Under the hood, we just added to itself times. The order we do it in doesn’t matter because of associativity.

So when you see manipulation like that, our group didn’t suddenly gain a multiplication binary operator, it’s just misleading shorthand.

Elliptic curves in finite fields

If we were to do elliptic curves over real numbers for a real application, they would be very numerically unstable because the intersection point could require a lot of decimal places to compute.

So in reality, we do everything with modular arithmetic.

But we lose none of the intuition we’ve gained above by using real numbers as a visual example.

Learn more with RareSkills

This material is from our zero knowledge course, see there to learn more. This post is part of a series on Zero Knowledge Proofs.

Originally Published September 1, 2023