ERC-7201 (formerly EIP-7201) is a standard for grouping storage variables together by a common identifier called a namespace, and also to document the group of variables via NatSpec annotation. The purpose of the standard is to simplify managing storage variables during upgrades.

Namespaces

Namespaces are a common approach in programming languages as a way to organize and group related identifiers, such as variables, functions, classes, or modules, to prevent naming conflicts. Solidity does not natively have the concept of namespaces, but we can simulate it. In our case, we want to group contract state variables together in a namespace.

The idea of using namespaces in Solidity was not first proposed by ERC-7201; it’s also utilized by the diamond proxy pattern (ERC-2535). To grasp the significance of using namespaces in upgradeable smart contracts, one must understand the problem that ERC-7201 aims to address.

A problem with inheritance

For demonstration purposes, let’s examine an upgradable contract consisting of a proxy contract and an implementation contract built using inheritance between a parent and a child contract. On the implementation side, we have a parent contract and a child contract, each containing a state variable in its initial slot. The storage structure of these implementation contracts will be replicated in the proxy contract, which could be a transparent proxy. For simplicity, let’s assume that each variable occupies exactly one slot, which means we are only using variables such as uint256 or bytes32.

The issue arises when the layout of the state variables in the implementation contracts is altered during an upgrade. Consider a scenario where the parent contract requires the addition of a new state variable. Consequently, the storage structure will be modified as follows:

This scenario presents a challenge: where variableB previously existed, variableC will now be placed. The upgrade disrupted the storage layout, resulting in the new variableC reading the old variableB value, which is a slot collision.

The gap approach

OpenZeppelin addressed this issue by inserting a “gap” at the end of each contract in its upgradeable contracts up to version 4. Below, we can observe the code of the ERC20Upgradeable.sol v4.9 contract.

![code snippet for uint256[45] private __gap variable](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/706568_b9dbd4392cf641d296c29878da33df6d~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_740,h_197,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_auto/706568_b9dbd4392cf641d296c29878da33df6d~mv2.png)

The size of the __gap variable is calculated so that the contract always uses 50 available storage slots, therefore the contract shown in the figure above has 5 state variables. Let’s incorporate this concept into our example.

If the parent contract with 5 state variables includes an array with 45 empty slots as a gap, the implementation (and proxy) contract storage structure will resemble the image below.

Now, there are 45 empty slots available for use by the parent contract in case of an upgrade. Suppose the parent contract requires adding a new state variable, variableN; in that scenario, we simply insert that variable before the gap and decrease the size of the gap by one, as the animation below illustrates:

The gap facilitates the insertion of new variables into contracts without disrupting existing functionality, acting as a placeholder for future additions and avoiding storage collisions. When using this approach, it is advisable to include a gap in all implementation contracts.

While this approach mitigates the problem of inserting variables in the parent contract, it doesn’t completely resolve all issues related to altering the layout in implementation contracts. For instance, if we create a new parent contract above the current parent contract, then everything below will be shifted down by the number of storage variables in the new parent, so relying solely on a gap won’t be effective.

Therefore, finding a method to adjust the layout of implementation contracts without producing slot collisions is essential.

The optimal solution would involve assigning each implementation contract in the inheritance chain its own dedicated storage location.

Unfortunately, Solidity currently lacks a native mechanism to do this (a namespace for variables in the contract). Therefore, constructions of this nature must be implemented within the bounds of Solidity and YUL. This can be achieved using structs. Let’s review how the storage layout works in Solidity and how to establish a namespace-based root layout.

A namespace-based root layout

The storage layout of a contract as generated by Solidity can be summarized as follows, where L represents the location in the storage, n is a natural number, and H(k) is a function applied to a specific type of key k, which can be, for example, a mapping key or the index of an array.

The formula above indicates that state variables can be found:

- In the root, which is slot 0 by default,

- Any element of the grammar plus a natural number.

- Within the keccak of a certain value calculated deterministically from a key and where the state variable is located from the root.

What we need to realize is that all locations in the storage layout depend on the root. Solidity assigns the value zero to the root for any contract.

If we want to create our own location for storing the variables of a contract, we need to “change” the root based on some label unique to that contract. It is precisely this label that we define as a namespace of the contract.

The concept of namespaces in smart contracts aims to ensure that the root of the storage layout of a contract using a namespace is no longer located in slot zero, but in a specific slot determined by the chosen namespace.

Achieving this solely with Solidity isn’t feasible since the compiler always uses slot zero as the root for the storage layout, but we can find a way using structs and assembly, as we will see shortly.

Before that, we will examine the formula proposed by ERC-7201 to calculate the value of the new root from a string that serves as a namespace.

A proposed formula for calculating namespace-based storage roots

If we are going to “change” the root storage slot of a namespaced contract, we need to define a formula to calculate this new root. The formula proposed in this ERC is as follows:

keccak256(keccak256(namespace) - 1) & ~0xff

The rationale behind the formula is as follows:

- Decrementing by 1 after generating the keccak256 namespace ensures that the hash preimage remains unknown.

- Taking the keccak256 hash a second time helps prevent potential conflicts with slots generated by Solidity, since the location of dynamic size variables in storage is determined by a keccak256 hash.

- Performing the AND NOT 0xff operation transforms the rightmost byte of the location to 00. This prepares for a future upgrade when Ethereum switches its storage data structure to Verkle Trees and 256 adjacent slots can be warmed at once.

The formula proposed above is used to guarantee a crucial property of the new root: that it does not collide with an original grammar element — i.e. the possible space of storage locations the Solidity compiler could assign a variable to by default.

If you want to try, a Solidity contract that calculates the root location value from a given namespace is as follows:

pragma solidity ^0.8.20;

contract Erc7201 {

function getStorageAddress(

string calldata namespace

) public pure returns (bytes32) {

return

keccak256(

abi.encode(uint256(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(namespace))) - 1)

) & ~bytes32(uint256(0xff));

}

}

If we plug in openzeppelin.storage.ERC20 we get the following hash.

// keccak256(abi.encode(uint256(keccak256("openzeppelin.storage.ERC20")) - 1)) ^ bytes32(uint256(0xff))

bytes32 private constant ERC20StorageLocation = 0x52C63247Ef47d19d5ce046630c49f7C67dcaEcfb71ba98eedaab2ebca6e0;

In fact, this is how OpenZeppelin sets the storage root for the ERC20UpgradeableContract v5 as we will see in the upcoming section.

Struct fields as variables

In the last section, we saw how to calculate the root of a contract based on its namespace. Now we need to be able to group storage variables together starting at that new root. We cannot declare state variables because by doing so, Solidity will start allocating variables from slot 0, which we want to avoid.

To group the variables together, we use a struct. Within a struct, the fields follow normal storage slot ordering. Consider the following contract:

contract StructStorage {

// **ERC-7201 uses a struct to group variables together, but the struct is never

// actually declared, nor any other state variable.**

struct MyStruct {

uint256 fieldA;

uint256 fieldB;

mapping(address => uint256) fieldC;

}

// Contract functions...

}

Hypothetically, if we declared this struct as the first storage variable (which ERC-7201 does not do), fieldA will be in slot 0, fieldB will be in slot 1, the base of the fieldC mapping will be in storage 2, and so forth. A formula to find the location in storage where a field of a struct-type variable can be written is as follows, where the struct base is the slot where the struct begins occupying the storage slots.

Note that it is the same formula as earlier for the storage layout; we just replaced the root with the base of the struct, i.e., the struct maintains the storage layout through its fields. This means we can use the struct base as the new root.

In the example above, the struct base is slot zero, but we can choose another slot to be the base of the struct. This can be done using YUL, as shown in the example below.

contract StructOnStorage {

// NO STATE VARIABLES

struct MyStruct{

uint256 fieldA;

mapping(uint => uint) fieldB;

}

function setMyStruct() public {

MyStruct storage myStruct; // Grab a struct

assembly {

myStruct.slot := 0x02 // Change its base slot

}

myStruct.fieldA = 100; // FieldA will be in the first slot from the base at 0x02, which is 0x02 itself

myStruct.fieldB[10] = 101; // The storage address of this mapping item will be calculated below

}

function getMyStruct() public view returns (uint256 fieldA, uint256 fieldBSingleValue) {

// keccak256(abi.encode(key, struct base + location inside the struct)

// The mapping is located in the second slot inside the struct, so struct base + 1

bytes32 locationSingleValue = keccak256(abi.encode(0x0a, 0x02 + 1));

assembly {

fieldA := sload(0x02) // Read storage at 0x02

fieldBSingleValue := sload(locationSingleValue)

}

}

}

When we use the myStruct.slot := 0x02 statement, we explicitly change the base of the struct and can mimic a storage layout where the root is no longer in slot zero. Inside the struct we must place all variables that would be state variables as struct fields. The struct base serves as the new root for its fields, precisely what we intended to achieve.

One disadvantage of this method is that we need to explicitly indicate the base of the struct every time we save or read its fields.

Since we always need to refer to the base of the struct, it is recommended to create a utility function to do this. In OpenZeppelin’s upgradeable contracts, there is a private function designed to create a pointer to the base of the struct. For instance, in ERC20Upgradeable.sol:

Below, we see how all “would be” state variables must be declared as fields of a struct.

abstract contract ERC20Upgradeable is Initializable, ContextUpgradeable, IERC20, IERC20Metadata, IERC20Errors {

/// @custom:storage-location crc7201:openzeppelin.storage.ERC20

struct ERC20Storage {

mapping(address account => uint256) _balances;

mapping(address account => mapping(address spender => uint256)) _allowances;

uint256 _totalSupply;

string _name;

string _symbol;

}

Let’s see an example of how we can use the utility function to retrieve a struct field, like the token name of the ERC20Upgradeable.sol contract.

/**

* @dev Returns the name of the token.

*/

function name() public view virtual returns (string memory) {

ERC20Storage storage $ = _getERC20Storage();

return $._name;

}

As can be seen above, when we want to retrieve storage variables, we simply call _getERC20StorageLocation() which returns the namespace storage root as bytes32.

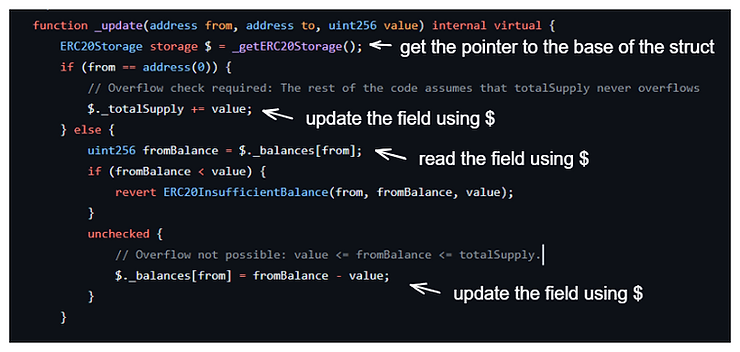

The same applies when we want to update a field. The $ pointer is at the base of the struct, so we can use the $.[field] syntax to read/update the fields. In the image below, we see a snippet of the _update function code from the ERC20Upgradeable.sol contract, and how it is used to update balances during a transfer.

Summary of how to implement a namespace-based root layout

To implement this pattern, simply follow these steps:

- Do not use state variables.

- Would be state variables must be defined as fields in a struct.

- Choose a unique namespace for the contract.

- Use a function to calculate the new root of this contract from the namespace. ERC-7201 proposes a function to be used.

- Create a utility function to return a reference to the struct base. Use assembly to explicitly indicate that the slot where the base of the struct is located is the slot calculated by the function defined in the previous item.

- Every time you read or update a struct field, use the utility function to point to the base of the struct.

In the next section, we will see how to document the utilization of namespaces within a contract.

NatSpec for custom storage location

Ethereum Natural Language Specification Format (NatSpec) is the method for comments that act as documentation within contracts. Here’s an example of a NatSpec comment documenting a function:

/**

* @dev Returns the name of the token.

*/

One of the goals of ERC-7201 is to propose a method for documenting the utilization of namespaces in NatSpec:

@custom:storage-location <FORMULA_ID>:<NAMESPACE_ID>

FormulaID represents the formula utilized for computing the storage root from the namespace, while namespaceId refers to the specific namespace under consideration. What is annotated is the struct, so the annotation must come right above it.

The formula proposed in this ERC is labeled as erc7201, so a NatSpec that uses this formula must be of the form:

@custom:storage-location erc7201:<NAMESPACE_ID>

As an example, in the ERC20Upgradeable contract, the chosen namespace is openzeppelin.storage.ERC20, so the annotation should be as follows

/// @custom:storage-location erc7201:openzeppelin.storage.ERC20

struct ERC20Storage {

...

}

Acknowledgments and Authorship

This article was written by João Paulo Morais in collaboration with RareSkills.

We would like to thank Hadrien Croubois (@Amxx) from OpenZeppelin for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Originally Published Jun 13