Our intent is not to be patronizing towards developers early in their journey with this article. Having reviewed code from numerous Solidity developers, we’ve seen some mistakes occur more frequently and we list those here.

By no means is this an exhaustive list of mistakes a Solidity developer can make. Intermediate and even experienced developers can make these mistakes too.

However, these mistakes are more likely to be made early in the learning journey so it is worth listing them.

1. Division before multiplication

In Solidity, the division operation should always be the last operation because division rounds numbers down.

For example, if we want to compute that we should pay someone 33.33% interest, the wrong way to do it is:

interest = principal / 3_333 * 10_000;

If the principal is less than 3,333, the interest will round down to zero. Instead, the interest should be computed in the following manner:

interest = principal * 10_000 / 3_333;

Here is the math behind how the rounding fails in the first example and succeeds in the second:

**// Wrong way:**

If principal = 3000,

interest = principal / 3333 * 10000

interest = 3000 / 3333 * 10000

interest = 0 * 10000 (rounding down in division)

interest = 0

// **Correct Calculation:**

If principal = 3000,

interest = principal * 10000 / 3333

interest = 3000 * 10000 / 3333

interest = 30000000 / 3333 interest approx 9000

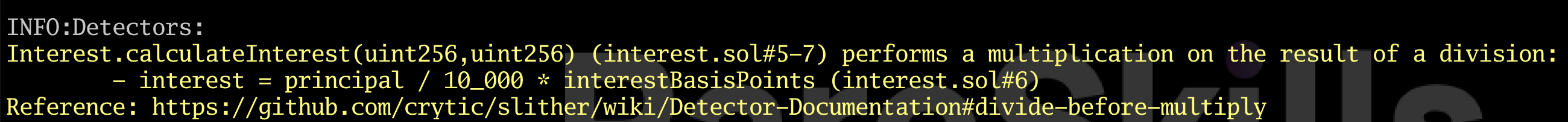

Catching the issue with Slither

Slither is a static analysis tool by Trail of Bits that parses the codebase to pattern match common mistakes.

If we create the following (faulty) contract interest.sol

contract Interest {

// 1 basis point is 0.01% or 1/10_000

function calculateInterest(uint256 principal, uint256 interestBasisPoints) public pure returns (uint256 interest){

interest = principal / 10_000 * interestBasisPoints;

}

}

And in the terminal run

slither interest.sol

we get the following warning:

In this case, it is saying we divide before multiply, which in general is something to avoid.

2. Not following check-effects-interaction

In Solidity, following the “check-effects-interaction” pattern is crucial to prevent re-entrancy attacks. This means that calling another contract or sending ETH to another address should be the last operation in a function. Failure to do so can leave the contract vulnerable to malicious attacks.

The following contract BadBank does not follow check-effects-interaction and thus can be drained of ETH.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.26;

// DO NOT USE

contract BadBank {

mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

constructor()

payable {

require(msg.value == 10 ether, "deposit 10 eth");

}

function deposit()

external

payable {

balances[msg.sender] += msg.value;

}

function withdraw() external {

(bool ok, ) = msg.sender.call{value: balances[msg.sender]}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

}

}

The following attack contract can be used to drain the bank:

contract BankDrainer {

function steal(BadBank bank) external payable {

require(msg.value == 1 ether, "send deposit 1 eth");

bank.deposit{value: 1 ether}();

bank.withdraw();

}

receive() external payable {

// msg.sender is the BadBank because the BadBank

// called `receive()` when it transfered either

while (msg.sender.balance >= 1 ether) {

BadBank(msg.sender).withdraw();

}

}

}

You can test the code in Remix here. The following video demonstrates the hack.

The reason this hack is possible is because the BadBank’s withdraw() function calls the receive() function in BankDrainer before updating the balances. Sending ether is equivalent to calling the receive() or fallback() function on another contract.

Therefore, always call the function of another smart contract or send the Ether last. The category of attack here is called re-entrancy. You can learn more about this attack in our re-entrancy article.

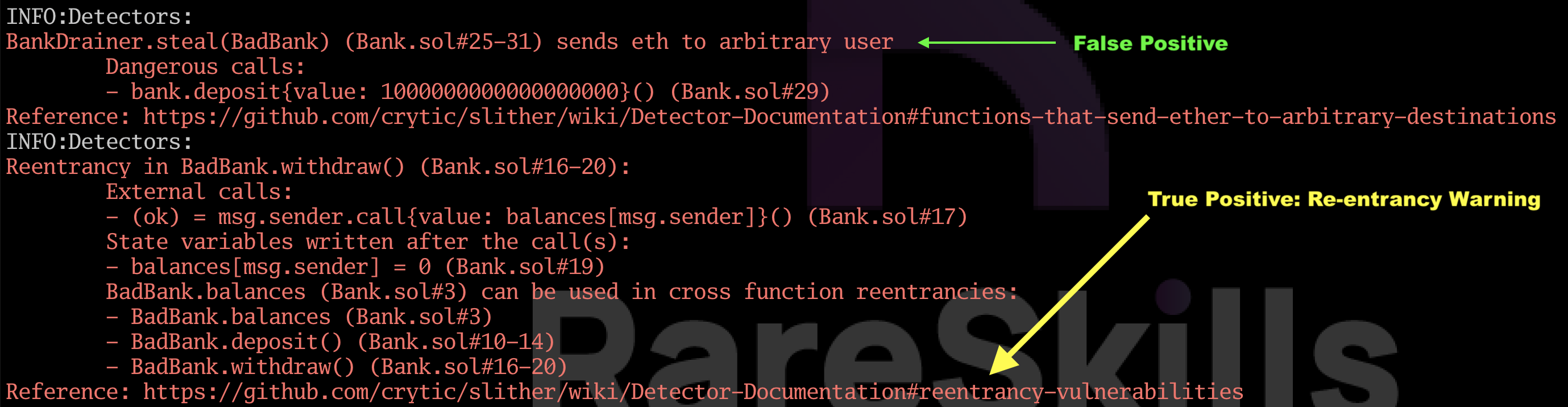

When we run Slither on the code above, Slither gives us two warnings:

The first warning, that it “sends eth to an arbitrary user” is a false positive. It is true that anyone can call withdraw, but the amount they can withdraw is limited to their balance (at least initially!).

However, Slither does correctly detect the re-entrancy vulnerability.

3. Using transfer or send

Solidity has two convenient functions transfer() and send() to send Ether from the contract to the destination. However, you should not use these functions.

The Consensys blog on why you should not use transfer or send is a classic that every Solidity developer must read at some point.

Why do these functions exist?

After the DAO hack, which split Ethereum into Ethereum and Ethereum Classic, developers were very scared of re-entrancy attacks. To avoid such attacks, transfer() and send() were introduced as they limit the amount of gas available to the recipient. It results in preventing re-entrancy by starving the recipient of the gas needed to execute further code.

Example scenario:

You can replace the

(bool ok, ) = msg.sender.call{value: balances[msg.sender]}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

in the example previously with payable(msg.sender).transfer(balances[msg.sender]); and you will see the Bank is no longer vulnerable.

However, this will break integrations when the contract is expecting to receive enough gas to respond to the incoming Ether. For example, if the target contract tries to credit the ETH to the sender, this will fail because it doesn’t have enough gas to finish the bookkeeping.

Consider the following example:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.26;

contract GoodBank {

mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

function withdraw() external {

uint256 balance = balances[msg.sender];

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

(bool ok, ) = msg.sender.call{value: balance}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

}

receive() external payable {

balances[msg.sender] += msg.value;

}

}

contract SendToBank {

address owner;

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

}

function depositInBank(

address bank

) external payable {

require(msg.sender == owner, "not owner");

// THIS LINE WILL FAIL

payable(bank).transfer(msg.value);

}

function withdrawBank(

address payable bank

) external {

require(msg.sender == owner, "not owner");

// this triggers the receive function

GoodBank(bank).withdraw();

// the receive function has completed

// and now this contract has a balance

// send it to the owner

(bool ok, ) = msg.sender.call{value: address(this).balance}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

}

// we need this to receive Ether from the bank

receive() external payable {

}

}

You can test the code above here in Remix. And here is a video demonstrating the failed transfer.

The transaction fails because receive() runs out of gas when incrementing the sender’s balance.

So don’t use transfer or send and don’t write re-entrant code. The first option is to replace transfer or send with address(receiver).call{value: amountToSend}(""). Alternatively, one can use the OpenZeppelin Address library to do the same thing. Both methods are shown below:

import {Address} from "@openzeppelin/contracts/utils/Address.sol";

contract SendEthExample {

using Address for address payable;

// both these functions do the same thing. Note that OZ requires

// payable addresses, but a low-level call does not

function sendSomeEthV1(address receiver, uint256 amount) external payable {

payable(receiver).sendValue(amount);

}

function sendSomeEthV2(address receiver, uint256 amount) external payable {

(bool ok, ) = receiver.call{value: amount}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

}

}

Slither does not provide a warning about using transfer or send, but you should nonetheless avoid using them.

4. Using tx.origin instead of msg.sender

Solidity is a bit confusing in that there are two ways to determine “who is calling me” from the contract’s perspective: one is tx.origin and the other is msg.sender.

tx.origin is the wallet that signed the transaction. msg.sender is direct caller. If a wallet directly calls a contract

wallet → contract

then from the contract’s perspective, the wallet is both msg.sender and tx.origin.

Now consider if the wallet calls an intermediate contract which then calls the final contract:

wallet → intermediate contract → final contract

From the perspective of the final contract, the wallet is tx.origin and the intermediate contract is msg.sender.

Using tx.origin to identify the caller opens up a security vulnerability. Suppose the user is phished into calling a malicious intermediate contract

wallet → malicious intermediate contract → final contract

In this situation, the malicious intermediate contract gains all the privileges of the wallet, allowing it to do any action the wallet is authorized to do — such as move funds.

To learn more about the differences between msg.sender and tx.origin see our article on Detecting if an address is a smart contract.

Slither does not provide a warning regarding tx.origin.

5. Not using safeTransfer with ERC-20

The ERC-20 standard only states that the token should throw an error if the user tries to transfer more than their balance. However, if the transfer fails for some other reason, then the standard does not explicitly state what should happen.

The function signature for ERC-20transfer is:

function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) public returns (bool success);

which implies that the ERC-20 token should return false on failure.

In practice, ERC-20 tokens have been implemented in inconsistent ways: some reverting on failure, and others not returning any Boolean at all (i.e. not respecting the function signature).

The library SafeERC20 handles both kinds of ERC-20 tokens. Specifically, it makes a transfer call to the address, and

- If a revert happens,

SafeERC20bubbles up the revert. This handles tokens that revert on failure, but don’t necessarily return a Boolean. - If there is no revert, it checks whether data was returned at all

- if no data was returned and the token address turns out to be an empty address rather than a smart contract, the library reverts.

- if data was returned, and the return is a false value, then SafeERC20 reverts.

- Otherwise, the library does not revert, signaling a successful transfer.

Here is how the SafeERC20 library the SafeERC20 library from OpenZeppelin should be used:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC20/utils/SafeERC20.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol";

contract SafeTransferDemo {

using SafeERC20 for IERC20;

function deposit(

IERC20 token,

uint256 amount)

external {

token.safeTransferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

}

// withdraw function not shown

}

contract MyToken is ERC20("MyToken", "MT") {

constructor() {

// mint the supply of 10_000 tokens

// to the deployer

_mint(msg.sender, 10_000 * 1e18);

}

}

6. Using safeMath with Solidity 0.8.0 (or higher)

Prior to Solidity 0.8.0, variables could overflow if a math operation happened that resulted in a value larger than the variable could hold. In response to this, the SafeMath library from OpenZeppelin became popular. Here is how the library prevented overflow in addition:

function add(uint256 x, uint256 y) internal pure returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = x + y;

require(sum >= x || sum >= y, "overflow");

return sum;

}

The sum should always be larger than x or y. If that is not the case, an overflow occured and the function reverts.

In older codebases, you will often see this line:

using SafeMath for uint256;

and math being done in this manner:

uint256 sum = x.add(y);

However, you should not do this in Solidity 0.8.0 or higher because the compiler adds a built-in overflow check behind the scenes. Therefore, using the SafeMath library for basic arithmetic operations makes the code less readable and inefficient, with no additional safety gain.

7. Forgetting access control

Let’s use a minimal example. Can you spot the problem?

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC721/ERC721.sol";

contract NFTSale is ERC721("MyTok", "MT") {

uint256 public price;

uint256 public currentId;

function setPrice(

uint256 price_

) public {

price = price_;

}

function buyNFT() external payable {

require(msg.value == price, "wrong price");

currentId++;

_mint(msg.sender, currentId);

}

}

Anyone can call setPrice() and set it to zero before calling buyNFT().

Whenever you write a function that is public or external, ask yourself if there should be a restriction on who can call the function. Here is a subtle variation of the issue above:

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC721/ERC721.sol";

contract NFTSale is ERC721("MyTok", "MT") {

uint256 public price;

address owner;

uint256 public currentId;

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

}

modifier onlyOwner() {

require(msg.sender == owner, "onlyOwner");

_;

}

function setPrice(

uint256 price_

) public onlyOwner {

price = price_;

}

function buyNFT() external payable {

require(msg.value == price, "wrong price");

currentId++;

_mint(msg.sender, currentId);

}

}

Here, the developer has added an onlyOwner modifier, which grants access to only the designated user. In the above examples, the access control modifier ensures that only the contract owner can set the price, as seen in the setPrice function.

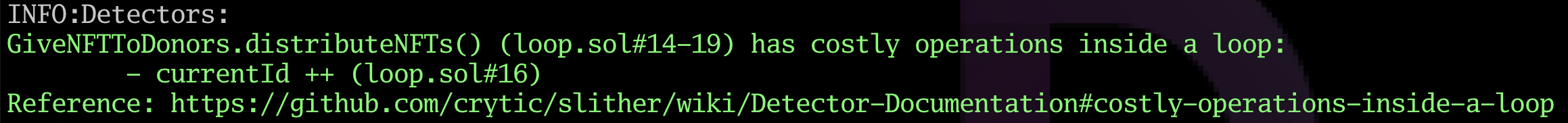

8. Expensive operations in a loop

Arrays that can grow without limit are problematic because the transaction costs to loop over them can become extremely high.

The following contract takes donations in Ether and adds the donors to an array. Later, the owner will call distributeNFTs() and mint all the donors an NFT. However, if there are many donors, it could become too expensive for the owner to complete the donation.

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC721/ERC721.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/access/Ownable.sol";

contract GiveNFTToDonors is ERC721("MyTok", "MT"), Ownable(msg.sender) {

address[] donors;

uint256 currentId;

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value >= 0.1 ether, "donation too small");

donors.push(msg.sender);

}

function distributeNFTs() external onlyOwner {

for (uint256 i = 0; i < donors.length; i++) {

currentId++;

_mint(msg.sender, currentId);

}

}

}

The function distributeNFTs() will attempt to iterate over the entire donor array. However, if the donor list in the array is large, this loop will result in a very high gas cost, making the transaction unfeasible. Slither will give you a warning about this situation similar to the following:

The solution to this is known as “pull over push.” Instead of sending each of the receivers their NFT, you have them call a function that transfers the NFT to the address, if that address calls the function.

9. Missing sanity checks on function inputs

Whenever you write a public function, explicitly write down the values you expect to be passed to the function arguments and make sure that require statements enforce it. For example, people should not be able to withdraw more than their balance. People should not be able to withdraw assets they didn’t deposit.

Consider the following examples:

contract LendingProtocol is Ownable {

function offerLoan(

uint256 amount,

uint256 interest,

uint256 duration)

external {}

function setProtocolFee(

uint256 feeInBasisPoints)

external

onlyOwner {}

}

The designer should think about what parameters are reasonable here. An interest rate over 1000% is unreasonable. A duration that is extremely short, such as 1 hour, is also unreasonable.

Similarly, the setProtocolFee function ought to have a sane upper bound on what fee the owner can set, or the users might get surprised when the fees to use the protocol go up to an unreasonable level all of a sudden.

To implement the sanity checks, we simply add require statements that bound the acceptable range of inputs.

When designing a public function always consider what range of parameters make sense for the function arguments.

10. Missing code

Some bugs in Solidity happen due to missing code rather than buggy code. The following NFT minting contract allows the owner to specify who is allowed to mint the NFT and how much. (This is not a gas-efficient way to do this, but we want to focus on the principle at hand).

Here is the code, can you spot what is missing?

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC20/utils/SafeERC20.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC721/ERC721.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/access/Ownable2Step.sol";

contract MissingCode is ERC721("MissingCode", "MC"), Ownable(msg.sender) {

uint256 id;

mapping(address => uint256) public amountAllowedToMint;

function mint(

uint256 amount

) external {

require(amount < amountAllowedToMint[msg.sender],

"not enough allocation");

for (uint256 i = 0; i < amount; i++) {

id++;

_mint(msg.sender, id);

}

}

function setAmountAllowedToMint(

address[] calldata minters,

uint256[] calldata amounts

) external onlyOwner {

require(minters.length == amounts.length,

"length mismatch");

for (uint256 i = 0; i < minters.length; i++) {

amountAllowedToMint[minters[i]] = amounts[i];

}

}

}

The problem is that the amount a buyer mints isn’t deducted from amountAllowedToMint so the “limit” isn’t really applied. An address in the mapping could call mint() as many times as they want to.

There should be an additional line amountAllowedToMint[msg.sender] -= amount after the _mint() function.

11. Not fixing the Solidity pragma

When you read the code of Solidity libraries, you’ll often see something like

//SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

at the top. Because of this, newer developers tend to blindly copy this pattern.

However, setting the Solidity version with ^0.8.0 is only appropriate for libraries. The author distributing the library doesn’t know the exact version a later programmer will compile it with, so they only set a minimum version.

As a developer deploying the application, you know which version of the compiler you are using to compile the code. Therefore you should lock the version to the exact one you used so it’s clearer to others auditing the code which version of the Solidity compiler you used. For example, instead of putting pragma solidity ^0.8.0 write the exact version pragma solidity 0.8.26. It will clarify things for others auditing the code with the specified version.

12. Not following the style guide

We’ve documented the Solidity style guide in a separate blog post.

Here are the highlights:

- constructor is the first function

- then

fallback()andreceive()(if the contract has them) - then

externalfunctions,publicfunctions,internalfunctions, andpurefunctions - within each group

- the

payablefunctions go first - followed by the non-

payablenon-viewfunctions - and the

viewfunctions go last

- the

13. Missing logs or incorrectly indexed logs

In Ethereum, there is no native method to list all transactions sent to a specific smart contract, except by searching for this information in block explorers. However, this can be achieved by having the contract emit events.

Here are some general rules about events:

- Any function that can change a storage variable should emit an event.

- The event should contain enough information for someone auditing the logs can determine what value the storage variable took at that time.

- Any

addressparameters in the event should beindexedso that it is easy to drill down on the activity of a particular wallet. - View and pure functions should not contain events because they do not change the state.

You can read more about this in our article on events in Solidity and Ethereum.

In general, if you change a storage variable or move Ether in and out of the contract, you should emit an event.

14. Not writing unit tests

How do you know the contract works in every possible scenario it will encounter, unless it has actually been tested?

In our view it is somewhat surprising that smart contracts get deployed without unit tests. This should not be the case.

See our tutorial on Solidity unit tests here.

15. Rounding in the wrong direction

If you divide 100/3 you will get 33 even though the “correct” answer is 33.33333 because Solidity does not support floats. In that case, 0.3333 of whatever unit you are measuring has disappeared, because you are forced to “round down” when division is used. Here is the golden rule of division:

Always round so the user loses or the protocol gains.

For example, if you are calculating how much a user needs to pay for something, then division will cause the estimate to be lower than it should be. In the example above, the user gets a 0.3333 discount.

Situation 1: Calculating how much the protocol pays

If we are computing 100/3 to determine how much the smart contract pays the user, then the smart contract will underpay the user. This is the correct way to do it. The user will not be able to bleed value from the protocol.

Situation 2: Calculating how much the user pays

On the other hand, if we are computing 100/3 to determine how much the user should pay the smart contract, then we have a problem, because the user pays 0.333 less than they should. If the user is able to sell that asset at a 0.333 profit, then they can repeat the process until they drain the protocol!

The correct thing to do in this circumstance is to add one to the division so that what we lost in the decimals is regained. That is, we should compute how much the user pays as 100/3 + 1, so the user has to pay 34 for an asset worth 33.333. The small amount of value they lose out on will prevent them from robbing the smart contract.

Learn more about how to properly handle fractions in our fixed-point math article.

16. Not running a formatter

There’s no need to reinvent the wheel with formatting Solidity code. You can use the forge fmt in Foundry or use the tool solfmt. It will make your code easier for the reviewer to read.

The following code is unnecessarily difficult to read:

contract GoodBank {

mapping(address=>uint256) public balances;

function withdraw () external {

uint256 balance=balances[msg.sender];

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

(bool ok,) =msg.sender.call{value: balance}("");

require(ok,"transfer failed");

}

receive() external payable {

balances[msg.sender]+=msg.value;

}

}

It should be run through a formatter so the spacing is more uniform:

contract GoodBank {

mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

function withdraw() external {

uint256 balance = balances[msg.sender];

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

(bool ok,) = msg.sender.call{value: balance}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

}

receive() external payable {

balances[msg.sender] += msg.value;

}

}

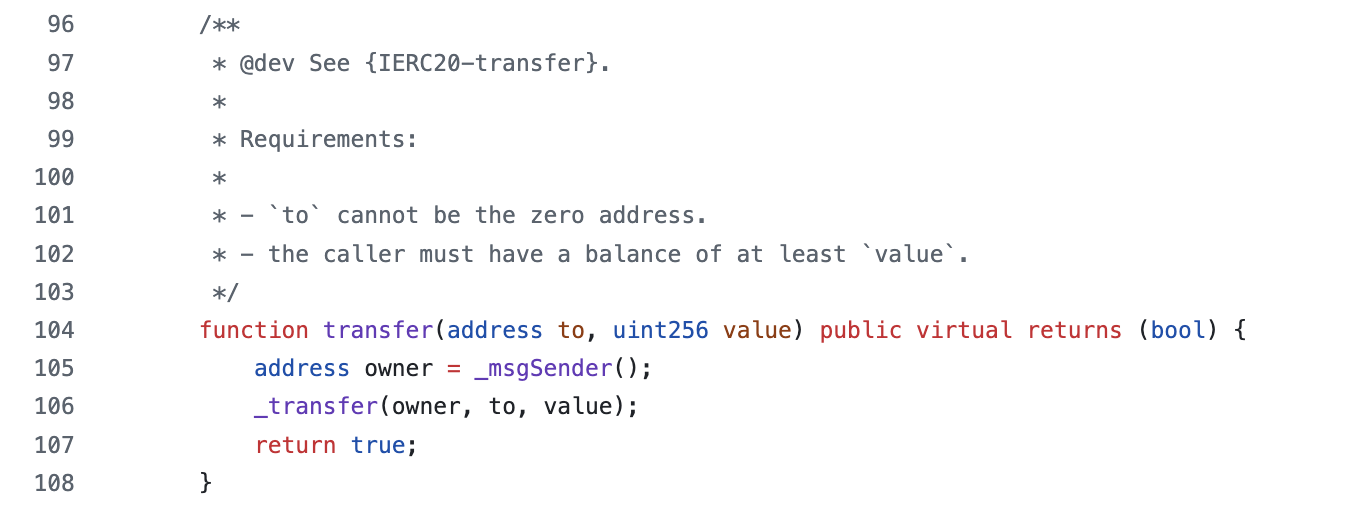

17. Using _msgSender() in contracts that do not support metatransactions

New Solidity developers are often confused by the frequent use of _msgSender() in OpenZeppelin contracts. For example, here is the OpenZeppelin ERC-20 library using _msgSender():

Unless you are building a contract that supports gasless or metatransactions, use regular msg.sender instead of _msgSender().

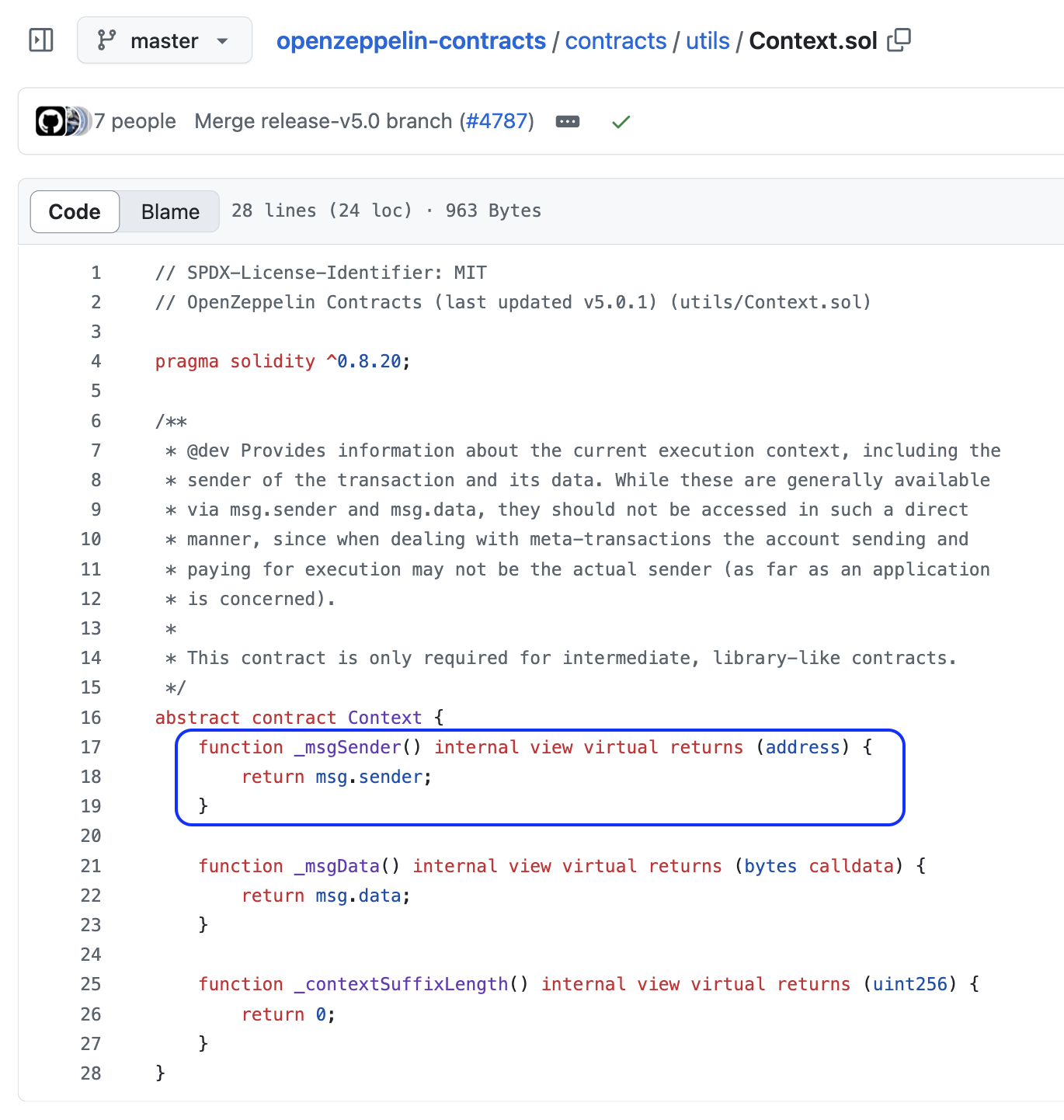

_msgSender() is a function created by the OpenZeppelin contract Context.sol:

This is only used in contracts that support metatransactions.

A metatransaction or gasless transaction is where a relayer sends the transaction on behalf of a user and pays the gas for them. Because the transaction came from a relayer, msg.sender won’t be the “original” sender. Smart contracts that use metatransactions encode the “true” msg.sender elsewhere in the transaction and signify the “true” msg.sender by overriding the _msgSender() function.

If you aren’t doing any of those things, there is no reason to use _msgSender(). Use msg.sender instead.

18. Accidentally committing API keys or private keys to Github

While we haven’t seen this occur too frequently, the few times it does happen results in extremely catastrophic outcomes. If you put API keys or private keys in a .env file, always add the .env file to the .gitignore file.

19. Not accounting for frontrunning, slippage, or the delay between transaction signing and execution

Frontrunning is a counterintuitive issue with Solidity contracts because its analogs rarely occur web2 programming.

Example 1: Changing the price while the buy transaction is pending

Consider the following contract, which allows a seller of an NFT to swap with a buyer for USDC in one transaction. This theoretically has the benefit that neither party has to send their token first and trust the counterparty will send their token.

However, it has a frontrunning vulnerability. The seller can change the price of the swap while the swap transaction is pending.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC20/utils/SafeERC20.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC721/ERC721.sol";

contract BadSwapERC20ForNFT is Ownable(msg.sender) {

using SafeERC20 for IERC20;

uint256 price;

IERC20 token;

IERC721 nft;

address public seller;

constructor(IERC721 nft_, IERC20 token_) {

nft = nft_;

token = token_;

seller = msg.sender;

}

function setPrice(uint256 price_) external {

require(msg.sender == seller, "only seller");

price = price_;

}

// the buyer calls this function

function atomicSwap(uint256 nftId) external

// requires both the seller and buyer

// to approve their tokens first

token.safeTransferFrom(msg.sender, owner(), price);

nft.transferFrom(owner(), msg.sender, nftId);

}

}

Whenever a user has tokens being transferred from them, the user should always be required to pass data that specifies the maximum amount they are willing to send so that the seller cannot change the price while the buy transaction is pending.

Example 2: NFT that goes up in price with each purchase

The following NFT sales are programmed to increase the price by 5% with each purchase. It has a similar issue as the one above. The price at the time the buyer signs the transaction might not be the same price when the transaction is confirmed. If 10 buyers send a buy transaction at the same time, then 9 of them are going to pay a higher price than they were expecting.

When a contract computes how many tokens to transfer from a user, the user should specify a limit on the maximum they will allow to be transfered from their account.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.25;

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC20/utils/SafeERC20.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/token/ERC721/ERC721.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/[email protected]/access/Ownable2Step.sol";

contract BadNFTSale is ERC721("BadNFT", "BNFT"), Ownable(msg.sender) {

using SafeERC20 for IERC20;

uint256 price = 100e6; // USDC / USDT have 6 decimals

IERC20 immutable token;

uint256 id;

constructor(IERC20 token_) {

token = token_;

}

function buyNFT() external {

token.safeTransferFrom(msg.sender, owner(), price);

price = price * 105 / 100;

id++;

_mint(msg.sender, id);

}

}

There is an even more subtle issue: the owner might change the token while a buyer’s transaction is still pending! Now, it’s unlikely that the buyer approved the contract for the new token, so the transferFrom will probably fail. But in a more complex contract that could realistically have multiple approvals, this would be an issue to watch out for.

20. Functions that do not account for users making the same transaction multiple times

Smart contracts need to account for the possibility that a user does the same transaction more than once. Consider the following example:

contract DepositAndWithdraw {

mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

function deposit() external payable {

balances[msg.sender] = msg.value;

}

function withdraw(

uint256 amount

) external {

require(

amount <= balances[msg.sender],

"insufficient balance"

);

balances[msg.sender] -= amount;

(bool ok, ) = msg.sender.call{value: amount}("");

require(ok, "transfer failed");

}

}

If deposit is called twice, then the first balance will be overwritten by the second transaction and that money will be lost. For example, if the user calls deposit() with a value of 1 ETH, then calls deposit() again with a value of 2 ETH, then the balance of that address will be 2 ETH even though they deposited 3 ETH. The correction is to increment the balance, i.e., balances[msg.sender] += msg.value;.