Cairo is a programming language designed for provable, verifiable computation, particularly within the context of zero-knowledge systems like Starknet, a Layer 2 (L2) network on Ethereum.

Cairo is purpose-built to enable STARK-based proofs of program execution. This allows computations to be verified efficiently off-chain and then proven on-chain with succinct, trustless proofs.

Though the language was created for blockchain use cases, Cairo is flexible within its domain, as it supports off-chain verifiable computation with cryptographic integrity. Unlike Solidity, Cairo can be run outside the context of smart contracts. In that sense, Cairo behaves almost like a general-purpose language constrained to smart contracts and provable offchain computation.

This article gives an overview of how the language works. We will cover major data types, control flow mechanisms, and commonly used data structures.

Cairo’s role in Starknet

Starknet uses STARKs (Scalable Transparent Arguments of Knowledge) to enable the execution of complex computations off-chain while preserving the security and decentralization of Ethereum.

All Starknet smart contracts are authored in Cairo. These contracts compile into an intermediate representation called Sierra, which is then compiled into Casm (Cairo Assembly), a low-level language that CairoVM understands. CairoVM executes the Casm instructions deterministically, produces an execution trace, and ensures the program follows the constraints required for STARK proof generation.

This article introduces the basics of the Cairo programming language and shows how it can be used as a general-purpose language outside the context of smart contracts. Before moving on to the next section, follow the steps below to set up the development environment.

Setting up the development environment

-

Create an empty directory and navigate into it.

The directory can have any name, in this example, it’s called

cairo_playground:mkdir cairo_playground && cd cairo_playground -

Create a source folder inside the

cairo_playgrounddirectory:mkdir src -

Inside the

srcfolder, create two files:playground.cairo(name can vary) andlib.cairo:touch src/playground.cairo && touch src/lib.cairo -

Add the following content to the new files.

playground.cairo:#[executable] fn main() { // Print message to terminal. println!("Hello from Rareskills!!!"); }lib.cairo:mod playground; -

Create a

Scarb.tomlfile in the project root (cairo_playground):touch Scarb.tomlAdd the following content:

[package] name = "cairo_playground" # HAS TO BE THE NAME OF THE ROOT DIRECTORY version = "0.1.0" edition = "2024_07" [cairo] enable-gas = false [dependencies] cairo_execute = "2.12.0" [[target.executable]] # A PATH TO THE FUNCTION WITH THE #[executable] ANNOTATION # <root-directory>::<file-name>::<function-name> function = "cairo_playground::playground::main"The

#[executable]annotation will be explained in a later subsection.

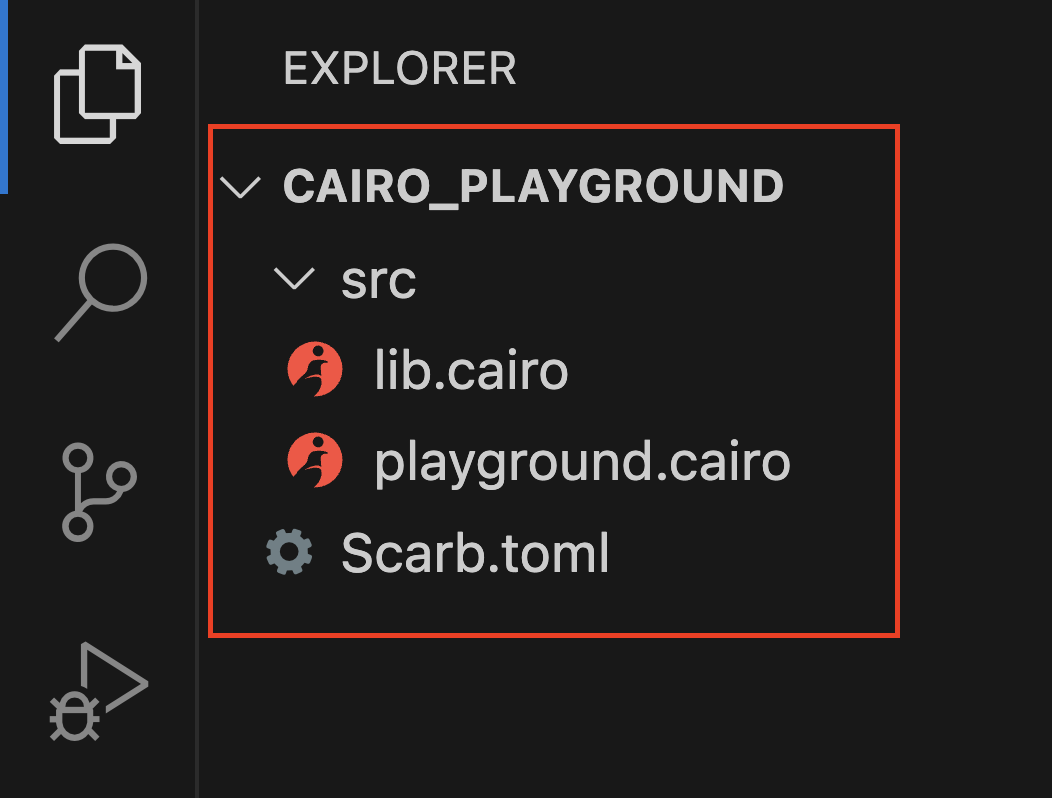

After completing the setup, the directory should have a structure similar to this:

Lastly, to test the Cairo program (playgroung.cairo), run the following command:

scarb execute

The Cairo language syntax essentials & data types

Cairo’s syntax is inspired by Rust, but optimized for provable, verifiable computing. Before we explore data types and logic, it’s essential to understand the building blocks, such as variable and function declarations in Cairo.

Declaring Variables: let, mut and const

Cairo is statically typed, and all variables must have their type declared at compile time. The let keyword is used during variable declaration, followed by a name, a colon, a type, and then the value:

// let <NAME>: <dataType> = <value>;

let count: u8 = 42;

let name: felt252 = 'bob';

let active: bool = true;

Variables mutability

Variables in Cairo are immutable by default. They can not be modified after assignment. To enable mutation, the mut keyword is used, as shown below.

// let mut <NAME>: <Type> = <value>;

let mut total: u128 = 0;

total = total + 10;

Declare a constant

In Cairo, the const keyword is used to define fixed values that are known during compilation and cannot be changed at runtime. Constants are hardcoded into the program source code, meaning they do not occupy memory, and accessing them has zero runtime cost.

Here is how to declare a constant:

// const <NAME>: <Type> = <value>;

const DECIMALS: u8 = 18;

Declaring functions in Cairo

Functions in Cairo are declared using the fn keyword. They support parameter passing, return values, and follow a strict typing system.

Let’s look at the multiply function below. The function takes two parameters(x, y) of type felt252, and also returns a felt252 value after the arrow(-> felt252 {..) as shown below:

// the function takes two parameters: `x` and `y`,

// both of type `felt252`, and returns a value of type `felt252`.

fn multiply(x: felt252, y: felt252) -> felt252 {

// The result of the multiplication expression is implicitly returned.

x * y

}

#[executable]

fn main() {

// Calls the multiply function with literal felt252 values: 3 and 4.

let result = multiply(3, 4); // result = 12

println!("This is the value of multiply(3, 4): {}", result);

}

In a function, we can return a value explicitly using the return keyword. However, as seen in the multiply function above, it’s also possible to return a value implicitly. When the last expression in a function body is not followed by a semicolon, its result is automatically returned.

The #[executable] attribute explained

The #[executable] attribute marks a function as an entry point that can be invoked directly by the Cairo runner. The Cairo runner is the program responsible for executing compiled Cairo code, looking for functions marked with #[executable] as the starting point.

Without this attribute, the function is not exposed as a top-level entry point and cannot be executed on its own.

In the example above, the multiply function is a regular function: it can be called by other functions in the program but cannot be executed directly on its own. In contrast, the main function is marked with the #[executable] attribute, which designates it as an entry point that can be run directly by the Cairo runner.

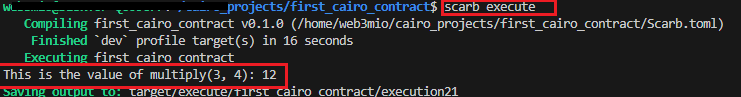

To execute main, above, enter the scarb execute command in your terminal. The output is shown below:

Note: The #[executable] attribute is not applicable to smart contracts.

In fact, the example above is not a smart contract, but a regular Cairo program. This is possible because, unlike Solidity that is domain-specific, Cairo can be executed outside the context of a smart contract. Using the Cairo runner, you can write and run standalone programs without deploying them to Starknet.

Printing data in Cairo functions

Now that you’ve seen how to run a standalone Cairo program, let’s explore how Cairo allows you to print values to the terminal.

The language provides two macros to print standard data types:

println!(which prints output followed by a newline)print!(which prints output inline, without a newline).

Both macros take at least one parameter: a ByteArray string, which may contain zero or more placeholders (e.g., {}, {var}), followed by one or more arguments that are substituted into those placeholders in order or by name.

See the code below to understand how print! or println! can be formatted:

#[executable]

fn main() {

let version = 2;

let released = 2023;

//contains one parameter: a ByteArray string

println!("Welcome to the Cairo programming language!");

// Positional formatting

println!("Version: {}, Released in: {}", version, released);

// Mixing named and positional placeholders

println!("Cairo v{} was released in {released}", version);

}

Data Types in Cairo

Now that we have seen how variables are declared in Cairo, let us explore the main data types in Cairo.

1. felt252: The Core Numeric Type

In Cairo, the most fundamental data type is a field element denoted by felt252. It is the default numeric type in the language, and represents an element of the prime field used by the Cairo VM. This field is shown below:

p = 2^{251} + 17*2^{192} + 1

This means a felt252 value can range from 0 up to p - 1. All arithmetic performed on felt252 values is modular arithmetic over this field. When a result exceeds p−1, it wraps back to 0, similar to how hours wrap around on a clock.

The code below shows how arithmetic operations greater than felt252 maximum value (p - 1) wraps to zero.

// The actual maximum value for felt252 in Cairo (p - 1 where p is the prime modulus)

const MAX_FELT252: felt252 = 3618502788666131213697322783095070105623107215331596699973092056135872020480;

#[executable]

fn main() {

let mut anyvalue = -5;

let result = MAX_FELT252 + anyvalue;

// When adding -5 to MAX_FELT252, we get MAX_FELT252 - 5 (still less than p)

if result != 0 {

println!("Result is less than p: {}", result);

println!("This means MAX_FELT252 - {} did not wrap to 0", 5);

}

// Now let's try adding a positive value that will cause wrapping

anyvalue = 1; // Reset to 1 to test wrapping

let wrap_result = MAX_FELT252 + anyvalue;

if wrap_result == 0 {

println!("Confirmed: MAX_FELT252 + {} wraps to 0", anyvalue);

} else {

println!("Unexpected: MAX_FELT252 + {} = {}", anyvalue, wrap_result);

}

// Test with a larger positive value

anyvalue = 10;

let wrap_result_10 = MAX_FELT252 + anyvalue;

println!("MAX_FELT252 + {} = {}", anyvalue, wrap_result_10);

}

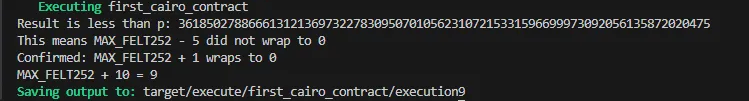

Terminal output:

Because of this wrapping behavior, arithmetic errors (i.e., overflow) caused by unintended wrapping can occur if not carefully handled.

To address this, Cairo also offers fixed-width integer types u8..u256 and signed integers i8..i256, which checks for overflow/underflow at runtime. If an operation tries to exceed the valid range the program will panic (i.e., halt with an error).

Use felt252 where extreme optimizations are needed, since all other types are ultimately represented as felt252 under the hood. For general arithmetic and safety, it is recommended to use integer types, as they provide built-in overflow protection.

Division in felt252

Field elements in Cairo’s felt252 type operate under finite field arithmetic principles, which means they do not support remainder or traditional integer division like fixed-width integers. Instead, the division a / b evaluates to a × b^(-1) mod P, where b is a non-zero value.

b⁻¹ is referred to as the modular multiplicative inverse of b modulo P.

If a = 1, and b=2, we would have 1 × 2⁻¹.

Since,

In the code block below, we will show how the proof above is true and see the behavior of felt252 division with or without remainder.

use core::felt252_div;

#[executable]

fn main() {

// (p + 1) / 2

let P_plus_1_halved = 1809251394333065606848661391547535052811553607665798349986546028067936010241;

assert!(felt252_div(1, 2) == P_plus_1_halved);

println!("this is the value of felt252_div(1, 2): {}", felt252_div(1, 2));

//divisions with zero remainder

assert!(felt252_div(2, 1) == 2);

println!("this is the value of felt252_div(2, 1): {}", felt252_div(2, 1));

assert!(felt252_div(15, 5) == 3);

println!("this is the value of felt252_div(15, 5): {}", felt252_div(15, 5));

//division with remainder

println!("this is the value of felt252_div(7, 3): {}", felt252_div(7, 3));

println!("this is the value of felt252_div(4, 3): {}", felt252_div(4, 3));

}

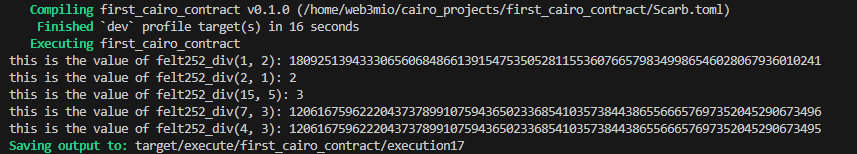

Terminal output:

As seen in the test above, division in the Cairo field works similarly to integer division when there’s no remainder.

However, it is different when the divisions have remainder(s). For example, if we divide 4 by 3, we aren’t asking “how many times does three go into four,” but rather, “what value multiplied by three gives four in this field?”

In field arithmetic, the answer is the product of four and the modular inverse of three. This ensures that the result, when multiplied by three, yields four modulo the field’s prime.

What happens when variables are declared without type?

In Cairo, when you assign a numeric literal without specifying a type, as shown below, the compiler automatically assumes the value is of type felt252.

let count = 42;

// count's is of type felt252

That’s because felt252 is Cairo’s default numeric type, similar to how int is used by default in some other languages.

2. Unsigned Integers: u8..u256

In Cairo, fixed-width integers such as u8, u16, u32, u64, and u128 are all subsets of the larger felt252 type, meaning their values can be fully fit in a felt252; they can be safely represented as field elements because their maximum values are less than the max value of felt252.

Table 1: Unsigned integers ranges

| Type | Size (bits) | Range |

|---|---|---|

u8 |

8-bit | 0 to 255 |

u64 |

64-bit | 0 to 2⁶⁴ - 1 |

u128 |

128-bit | 0 to 2¹²⁸ - 1 |

u256 |

256-bit | 0 to 2²⁵⁶ - 1 (composite) |

u256 , as seen in table 1, exceeds the max value of felt252 and, therefore, does not fit in a single field element. Under the hood, Cairo represents u256 as a struct composed of two u128 values:

struct u256 {

low: u128, // Least significant 128 bits

high: u128, // Most significant 128 bits

}

For example, the value 7 of type u256 is halved like so:

let value: u256 = 7;

// __________________________256-bit_____________________________

// | |

// 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000007

// ________high 128-bit__________ __________low 128-bit_________

// | | | |

// 0x00000000000000000000000000000000 00000000000000000000000000000007

3. Signed Integers: i8, i16, i32, i64, i128

Signed integers in Cairo are written using a lowercase i followed by the bit width, such as i8, i16, i32, i64, or i128. Each signed type can represent values within a range centered around zero, calculated using the formula:

to

For example, the range for i8 is -128..127.

Overflow/underflow behavior in signed & unsigned integers in Cairo

In the code below, we used the u256 (as a reference) to test the behavior of integers (signed & unsigned) when they encounter overflow/underflow.

// Maximum value for u256: 2^256 - 1

const MAX_U256: u256 = 115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007913129639935;

fn add_u256(a: u256, b: u256) -> u256 {

a + b

}

fn sub_u256(a: u256, b: u256) -> u256 {

a - b

}

fn multiply_u256(a: u256, b: u256) -> u256 {

a * b

}

#[executable]

fn main() {

println!("Testing u256 panic behavior");

println!("MAX_U256: {}", MAX_U256);

// Note: calls that panic will terminate the entire program immediately

//(comment out all other panic calls to see each result individually)

let result = sub_u256(MAX_U256, 1);

println!("result(less than MAX_U256): {}", result);

// This will panic on underflow

let result = sub_u256(0, 1);

println!("Underflow result: {}", result);

//returns -> error: Panicked with 0x753235365f616464204f766572666c6f77 ('u256_add Overflow').

// This will panic on overflow

let result = add_u256(MAX_U256, 1);

println!("Overflow result: {}", result);

//returns -> error: Panicked with 0x753235365f616464204f766572666c6f77 ('u256_add Overflow').

// This will also panic on overflow

let mult_result = multiply_u256(MAX_U256, 2); //

println!("Mult result: {}", mult_result);

//returns -> error: Panicked with 0x753235365f6d756c204f766572666c6f77 ('u256_mul Overflow').

}

As shown above, all arithmetic operations that exceed the maximum value of u256 result in a panic error.

4. bool: true or false

A bool is used to represent logical values: true or false. Internally, a bool is encoded as a felt252 with value 0 (false) or 1 (true).

Cairo Compound Types

Compound types group multiple values together, allowing for structured and expressive data representation in Cairo.

Tuples

Tuples hold fixed sets of values of different types. They’re useful for returning multiple values from functions or grouping related data temporarily.

let pair: (felt252, bool) = (42, true);

// Accessing tuple elements by destructuring

let (first_element, first_element) = pair;

Structs

Structs are custom data types with named fields.

// Define the struct

struct Point {

x: felt252,

y: felt252,

}

#[executable]

fn main() {

let p = Point { x: 3, y: 4 };

// Accessing struct fields

let x_coordinate = p.x;

let y_coordinate = p.y;

println!("The x coordinate of point p is: {}", x_coordinate);

println!("The y coordinate of point p is: {}", y_coordinate);

}

Enums

Enums are types with multiple named variants, where each variant can optionally hold data. They’re perfect for representing values that can be one of several different types.

enum Direction {

North,

South,

East,

West,

}

// Enum with associated data

enum Message {

Quit,

Move: Point,

Write: felt252,

Color: (felt252, felt252, felt252),

}

// Using enums with pattern matching

let msg = Message::Move(Point { x: 10, y: 20 });

match msg {

Message::Quit => { /* handle quit */ },

Message::Move(point) => { /* handle move with point data */ },

Message::Write(text) => { /* handle write with text */ },

Message::Color((r, g, b)) => { /* handle color with RGB values */ },

}

Strings, short strings, bytearray

Text handling in Cairo is lower-level compared to high-level languages. The language does not have a traditional String type like in Rust or JavaScript, but it provides two core primitives for handling textual data:

- Short strings: string literals encoded into

felt252(orbytes31), limited to 31 bytes. ByteArray: a built-in type for dynamically-sized ASCII characters and byte sequences.

Let’s walk through the details of these string types.

Short Strings: Compact ASCII in felt252

When your string representation is short or not more than 31 ASCII characters, you can represent it as a short strings. Short strings in Cairo are packed directly into a single felt252 with each character encoded using its ASCII value (1 byte = 8 bits). Since a felt252 holds 252 bits, you can store up to 31 ASCII characters in a single field element.

Let’s take the lowercase 'hello world', a total of 11 characters, which is well within the 31-character limit.

// Note the single quotes around the string.

let greeting: felt252 = 'hello world'; // Fits within 31 ASCII characters

// OR

let greeting: bytes31 = 'hello world'.try_into().unwrap(); // Fits within 31 ASCII characters

// ' h e l l o w o r l d '

// → ASCII bytes: 68 65 6C 6C 6F 20 77 6F 72 6C 64

// → Hex: 0x68656c6c6f20776f726c64

If we map each of the characters in the 'hello world' example to its ASCII code, and pack those bytes into a single hex value, from left to right we would have: 0x68656c6c6f20776f726c64.

Byte Arrays strings

The ByteArray type in Cairo is designed to handle ASCII characters and arbitrary byte sequences that exceed the 31-byte limit of a single felt252. This makes it essential for managing dynamic-length data.

// Note the double quotes around the long string.

let long_string: ByteArray = "Hello, Cairo! This is a longer string that exceeds 31 bytes and demonstrates ByteArray usage perfectly.";

Internally, ByteArray uses a hybrid storage structure. The code block below, shows how ByteArray struct includes three fields that work together to store byte data:

pub struct ByteArray {

pub(crate) data: Array<bytes31>, // Full 31-byte chunks

pub(crate) pending_word: felt252, // Incomplete bytes (up to 30 bytes)

pub(crate) pending_word_len: usize, // Number of bytes in pending_word

}

- The

datafield holds complete 31-byte chunks stored asbytes31. - The

pending_wordfield holds leftover bytes that don’t form a full chunk. - The

pending_word_lentracks the exact number of bytes stored inpending_word.

The pending_word can store at most 30 bytes, not 31. If you have exactly 31 bytes available, they are stored as a complete chunk in data. For byte arrays shorter than 31 bytes in total, data remains empty and all content resides in pending_word.

Now, let’s create a few ByteArray examples to see how data is stored based on length:

#[executable]

fn main() {

// Short string (≤30 bytes) - stored entirely in pending_word

let short_data: ByteArray = "Hello Cairo developers!"; // 23 bytes in pending_word

// Medium string (31-60 bytes) - one chunk in data + remainder in pending_word

let medium_data: ByteArray = "This is a longer string that demonstrates ByteArray storage"; // 58 bytes total

// Long string (>62 bytes) - multiple chunks in data + remainder in pending_word

let long_data: ByteArray = "ByteArray stores data efficiently using 31-byte chunks in the data field, with any remaining bytes stored in pending_word field"; // 127 bytes total

}

Control flow in Cairo

Cairo supports standard control flow constructs such as conditional statements and loops, which allow developers to write branching programs.

if, else if else

Cairo uses the if, else if, and else blocks for branching logic, just like in Rust or other mainstream languages.

Here is an example showing how if statements are written in Cairo.

use core::felt252_div;

#[executable]

fn main() {

let x: u32 = 5; // Explicitly type as u32

let wrecked_pie = felt252_div(22, 7);

let _result = if x > 10 {

wrecked_pie - 1000

} else if x == 10 {

0

} else {

wrecked_pie

};

println!("this is the value of result: {}", _result);

}

Note that if we had defined x as a felt252 in the example above, the program would fail at compile time. This is because felt252 does not implement the PartialOrd trait, which is required to use comparison operators like <, >, <=, and >=. This limitation is a deliberate design choice in Cairo to prevent cryptographic mistakes that could arise from relying on the numerical ordering of field elements.

Loops ( loop, while, and for)

Cairo supports three primary forms of loops: loop, while, and for, each with specific use cases and constraints.

loops: The loop keyword creates an infinite loop, similar to while true in other languages. It runs indefinitely until explicitly exited with a break statement. This construct is useful when the number of iterations is not known ahead of time, and you rely on internal conditions to terminate the loop.

Here’s an example of using loop to sum numbers until a condition is met:

fn loop_sum(limit: felt252) -> felt252 {

let mut i = 0;

let mut sum = 0;

loop {

if i == limit {

break;

}

sum += i;

i += 1;

}

sum

}

In this example, the loop continues indefinitely until i == limit, at which point break exits the loop.

while: The while loop in Cairo executes as long as a given condition evaluates to true. It is most suitable for conditional iteration when the end condition is evaluated at runtime. The loop condition must be deterministic and based on values known during execution.

let mut i = 0;

while i < 5 {

// Do something

i += 1;

}

for: The for loop in Cairo works only with statically defined ranges. This means you can iterate over a constant or literal range using the syntax for i in 0..n, where n must be a compile-time constant or a known value at the start of the loop.

In this example below, we looped over an array(which we will explain shortly) using the for keyword.

use core::array::ArrayTrait;

#[executable]

fn main() {

let mut a = ArrayTrait::new();

a.append(10);

a.append(20);

a.append(30);

a.append(40);

a.append(50);

let len = a.len();

for i in 0..len {

let val = a.at(i);

// You can use `val` here however you need

let _ = val;

}

}

Arrays and Dictionaries in Cairo

Arrays in Cairo are ordered collections of values of the same type. Due to Cairo’s immutable memory model, existing elements cannot be modified once added. Elements can be appended to the end using append() and removed from the front using pop_front(), which returns an Option<T> and advances the logical start position. This queue-like behavior allows FIFO (first-in, first-out) operations.

Arrays are implemented using the Array<T> type with methods provided by array::ArrayTrait. Hence, new arrays are created using the ArrayTrait::new() call.

The code below shows how to create a new array.

use array::ArrayTrait;

let mut numbers = ArrayTrait::<felt252>::new();

Local (memory) arrays are immutable by default. So we use let mut to make them mutable, as shown below.

Afterwards, we can add items into the array by calling the .append(value).

numbers.append(10); // the element 10 is appended to index 0

numbers.append(20); // the element 10 is appended to index 1

Alternatively, we can use array! to append items at compile-time sequentially:

let arr = array![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

Array Method

Each array is backed with built-in methods which is exposed through the array::ArrayTrait. Here are a Cairo’s array methods:

.new(): Creates an empty array..append(value): Adds an item to the end of an array..pop_front(): remove elements from the front of an array.len(): Returns the number of elements..pop_front(): Removes and returns the last element.isEmpty(): Returnstrueif the array is empty, else returnsfalse..get(index)orat(index): Reads an item at a specific index.

In Cairo, both .get(index) and .at(index) are used to access elements in an array, but they differ in behavior. The .get(index) method returns an Option<T>, which means the result could either be Option::Some(value) if the index is within bounds, or Option::None if it’s not. This makes .get() the safer choice, especially in situations where you can’t guarantee that the index is valid.

On the other hand, .at(index) gives you the value directly without wrapping it in an Option. While this makes access simpler when the index is known to be valid, it comes with a significant tradeoff: if the index is out of bounds, the program will panic and crash.

Arrays of multiple data types in Cairo

You cannot directly store multiple different data types in a single array, because arrays are homogeneous (require all elements to be of the same type).

However, you can work around this limitation by using a custom enum or struct to wrap different types in a single unified type.

The example below shows how to work around this using an enum.

use core::array::ArrayTrait;

//NOTE:

// The Drop trait allows automatic cleanup when this type goes out of scope.

// Basic types like felt252, u8, bool, etc. have automatic Drop implementations, But

// Custom types like enums and structs typically need to derive Drop explicitly.

// Felt252Dict or other non-droppable types cannot implement Drop.

#[derive(Drop)]

enum MixedValue {

Felt: felt252,

SmallNumber: u8,

Flag: bool,

FeltArray: Array<felt252>,

}

#[executable]

fn main() {

let mut mixed: Array<MixedValue> = ArrayTrait::new();

mixed.append(MixedValue::Felt(2025));

mixed.append(MixedValue::SmallNumber(7_u8));

mixed.append(MixedValue::Flag(true));

let mut nested_array: Array<felt252> = ArrayTrait::new();

nested_array.append(1);

nested_array.append(2);

nested_array.append(3);

mixed.append(MixedValue::FeltArray(nested_array));

}

Dictionaries (Felt252Dict<T> data type)

Similar to mapping in Solidity, the Felt252Dict<T> is a dictionary-like data type that represents a collection of key-value pairs where each key is unique and associated with a corresponding value T. It’s functionality or methods is implemented in the Felt252DictTrait trait in the core library.

The key type is restricted to felt252, while their value data type is specified. Internally, Felt252Dict<T> works as a list of entries with the value associated to each key initialized to zero. Once a new entry is set, the zero value is set as the previous entry. Hence, if a non-existent key is entered, the zero_default method under Felt252DictTrait will be called to return 0, instead of an error or an undefined value. However, this trait is not is not available for complex types (the reason is in the next subsection).

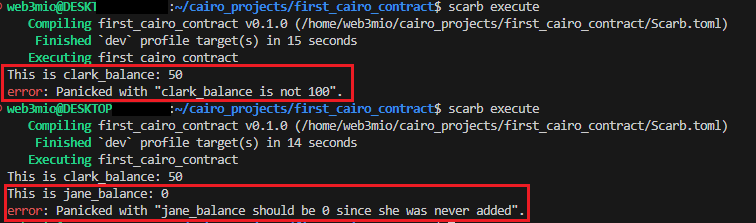

Here is a simple example of how to work around the Felt252Dict<T> key-value pair.

use core::dict::Felt252Dict;

#[executable]

fn main() {

// Create the dictionary

let mut balances: Felt252Dict<u64> = Default::default();

// Insert only 'clark'

balances.insert('clark', 50);

// Get balance for 'clark'

let clark_balance = balances.get('clark');

println!("This is clark_balance: {}", clark_balance);

assert!(clark_balance == 100, "clark_balance is not 100");

// Try to get 'jane' — not inserted, returns 0

let jane_balance = balances.get('jane');

println!("This is jane_balance: {}", jane_balance);

// Demonstrate that jane was not inserted by checking if the returned value is 0

assert!(jane_balance == 25, "jane_balance should be 0 since she was never added");

}

When we run the code above, the first assertion will fail because the key 'clark' was inserted with a value of 50, therefore, the condition clark_balance == 100 evaluates to false.

If we comment the first assertion out to allow the second one to run, the program will proceed to retrieve the balance for 'jane', who was never inserted into the dictionary. In Cairo, calling .get('jane') on a key that has not been explicitly inserted returns the default value of the value type, in this case, 0.

Compound types inside Dictionaries

let mut dict: Felt252Dict<u64> = Default::default();

// ALL possible keys now have value 0 (the zero value for u64)

let value = dict.get(999); // Returns 0, even though we never inserted anything

let mut dictArray: Felt252Dict<<Array<u8>>> = Default::default();

// ALL possible keys of dictArray do not have value 0

We mention earlier that dictionaries automatically initialize all keys to a “zero value” when created, through the the zero_default method. However, this behavior is not support for complex or composite types such as arrays and structs (including types like u256). This is because zero_default requires the type to have zero value that can be returned when a key hasn’t been explicitly set. Since complex types typically don’t implement this trait, Cairo requires that you manually handle initialization and existence checks when storing them in dictionaries.

To resolve this limitation, the Nullable<T> pointer type can be used in dictionaries to represent either a value or the absence of one (null). The dictionary stores pointers to heap-allocated values, and you explicitly check for null when reading.

The code below demonstrates how to store an array inside a Felt252Dict by wrapping them in Nullable<Array<felt252>>. This allows us to associate dynamic data (such as serialized values) with felt-based keys in a dictionary.

use core::dict::Felt252Dict;

#[executable]

fn main() {

// Create an array of felt252 values

let data = array![42, 13, 88, 5];

// Initialize a dictionary that maps felt252 keys to nullable byte arrays

let mut storage: Felt252Dict<Nullable<Array<u8>>> = Default::default();

// Convert our data to bytes and store in dictionary

let byte_data = array![0x2a, 0x0d, 0x58, 0x05]; // hex representation

storage.insert(1, NullableTrait::new(byte_data));

// Store another entry

let more_data = array![0xff, 0x00, 0xaa];

storage.insert(2, NullableTrait::new(more_data));

}

This example shows how arrays can be inserted into the dictionary using unique felt keys, with Nullable providing a safe wrapper that can represent either a value or an empty state.

Conclusion

Cairo is a Rust-like language with familiar control structures.

- The

felt252data type is the default for numeric types. Many data types get converted tofelt252behind the scenes. - Using signed and unsigned is preferred over

felt252type due to overflow protection. - Variables are immutable by default and must be declared

mutif their value will change in the future. - Cairo supports arrays and dictionaries for grouping data together.

This article is part of a tutorial series on Cairo Programming on Starknet